80 years ago, on 18 June 1940, powerful words were pronounced on the BBC, broadcast on both sides of the Channel: ‘the flame of French resistance must not and will not be extinguished’.

These words came from a rather unknown French General who had just arrived in London and was determined to fight on after the fall of France: Charles de Gaulle.

An ‘indissoluble union’

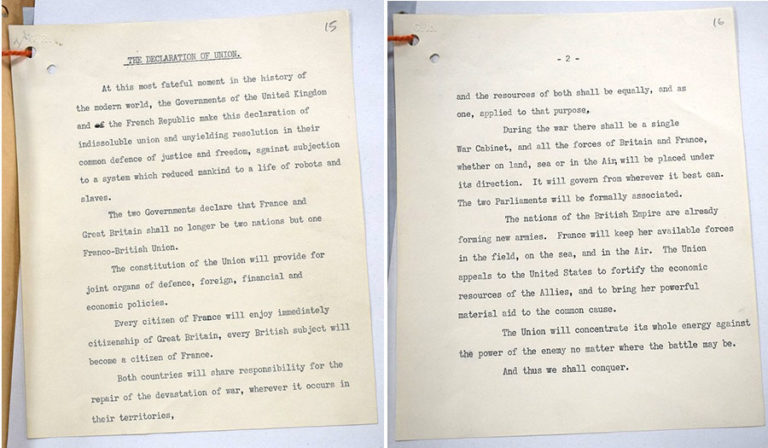

On 16 June 1940, 48 hours after the Germans entered Paris, officials on both sides on the Channel came up with a rather extraordinary proposal: an ‘indissoluble union’ between France and Britain. A declaration was drafted by the head of the Inter-Allied Commission, Jean Monnet, with his deputy René Pleven, French Undersecretary for National Defence and War Charles de Gaulle, Churchill’s personal assistant Desmond Morton, and Chief Diplomatic Adviser Robert Vansittart.

‘At this most fateful moment in the history of the modern world’, the declaration read, ‘the two governments declare that France and Great Britain shall no longer be two nations but one Franco-British Union’ (PREM 3/176).

Churchill had initially been against the idea of a union. When he took it to a War Cabinet meeting in the afternoon of 16 June, however, he declared: ‘in this grave crisis we must not let ourselves be accused of a lack of imagination’ (CAB 65/7/64).

The Declaration of Union was approved by the War Cabinet and it was agreed that de Gaulle should take it back to France so that Paul Reynaud, the French Premier, could discuss it with his ministers.

Churchill, accompanied by a small British delegation, was to travel to Concarneau, in Brittany, to meet with Reynaud and sign the declaration. This never happened. On 16 June, as Churchill was already on the special train taking him down to the coast, Paul Reynaud, having failed to gain the support of the French Cabinet, resigned. On 17 June, Marshal Philippe Pétain, who had replaced him, called for the fighting to cease.

‘I, General de Gaulle…’

General de Gaulle immediately left for Britain and arrived in London on 17 June. On 18 June at 22:00, he broadcast an appeal on the BBC. ‘Has the last word been said?’ he asked, ‘Must hope disappear? Is defeat final? No!’

He stressed that France was ‘not alone’ and could count on the support of her allies and her empire.

By all accounts, de Gaulle’s broadcast wasn’t widely heard on 18 June 1940, and it wasn’t recorded either. Still, he made the appeal which is today recognised as the starting point of French resistance:

‘I, General de Gaulle, currently in London, invite the officers and the French soldiers who are located in British territory or who might end up here, with their weapons or without their weapons, I invite the engineers and the specialised workers of the armament industries who are on British territory or who might end up here, to get in touch with me.’

The War Cabinet had agreed to the substance of the broadcast, but some thought the British Government should be cautious not to sever links to the French Government too quickly. At the Foreign Office, William Strang wrote on 19 June that de Gaulle’s message had ‘all the appearance of a challenge to the Government at Bordeaux’ and that Britain should tread carefully:

‘So long as we are gingering up the present French Government, and with some success, it would be disastrous if we should appear at the same time to be coquetting with a possible successor in London.’

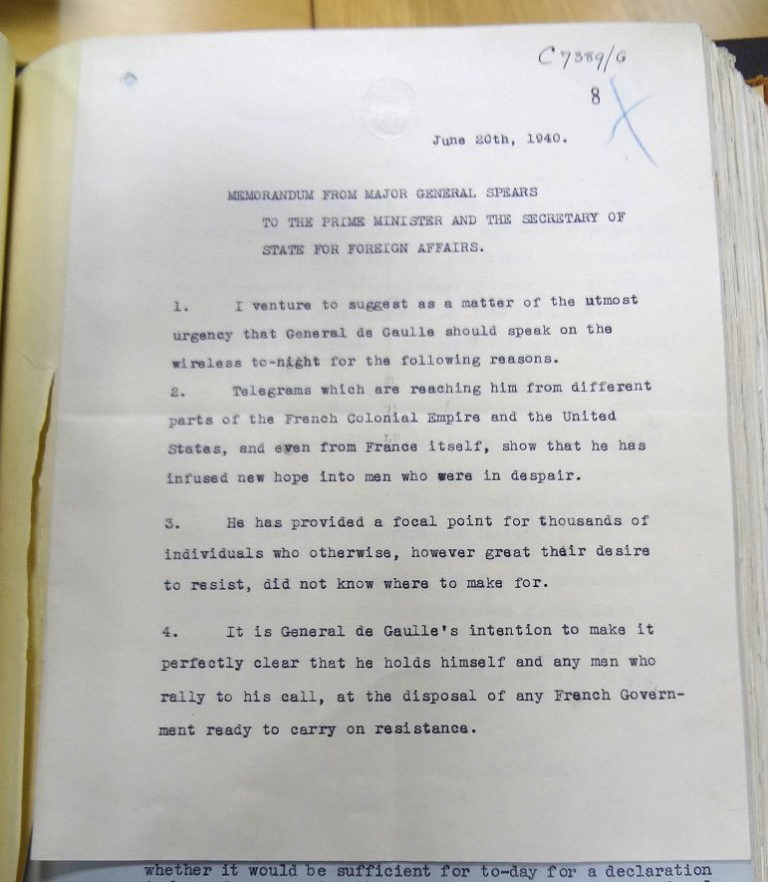

Others were more enthusiastic. ‘It could have been disastrous – and is fantastic!’ Robert Vansittart wrote on 19 June. Still, he thought de Gaulle shouldn’t broadcast again until the effect of his speech could be measured. Major General Spears, who had been Churchill’s personal representative to Reynaud, was full of praise for de Gaulle on 20 June, and stressed that he had ‘infused new hope into men who were in despair’ and ‘provided a focal point for thousands of individuals who otherwise, however great their desire to resist, did not know where to make for’ (FO 371/24349).

On 22 June 1940, at 18:36, France signed an armistice with Germany.

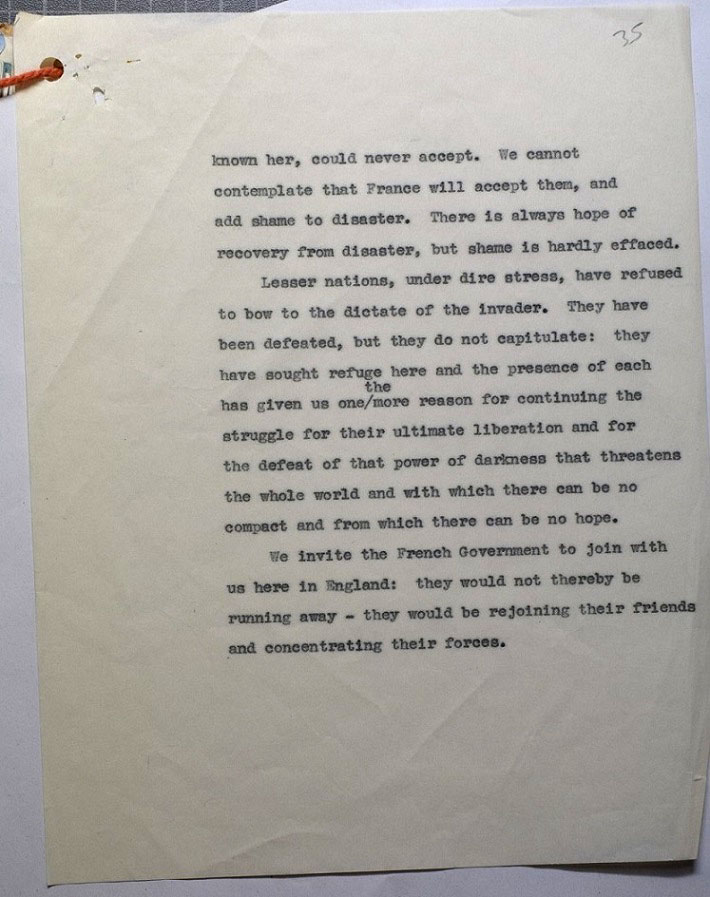

The British Government had done all they could to prevent it, making clear that they hadn’t released France from her obligation not to sign a separate armistice or peace, promising to ‘assist France to continue the struggle’, either from France itself or from the French colonies, and urging the French Government not to ‘surrender to a foe without honour, from whom no mercy can be expected’. Each communication was more pressing and more direct than the previous one. A telegram was sent to the British ambassador, Sir Ronald Campbell, who was asked to pass on a strong message:

‘We cannot contemplate that France will accept [the armistice terms] and add shame to disaster. There is always hope of recovery from disaster but shame is hardly effaced. Lesser nations, under dire stress, have refused to bow to the dictate of the invader, they have been defeated but they do not capitulate’ (PREM 3/174/4).

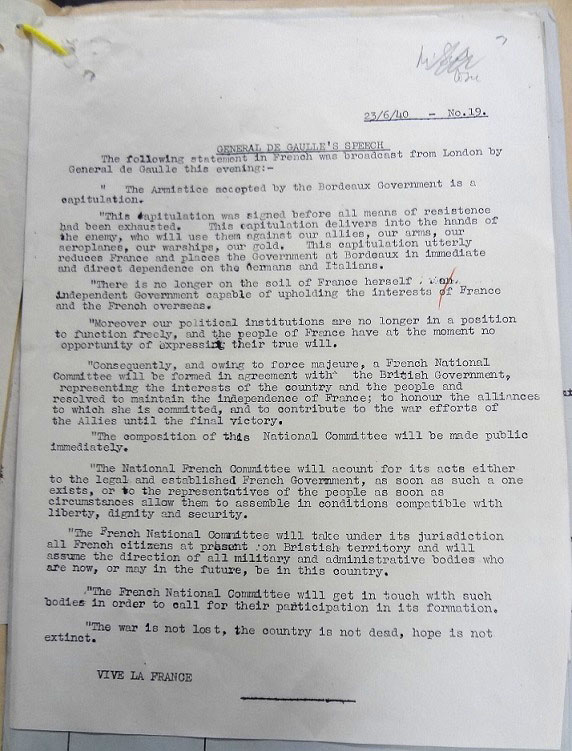

In the evening of 22 June, de Gaulle was back at the BBC to broadcast another appeal (this one was recorded and you can listen to it here). He described the armistice as a ‘capitulation’ bringing ‘subjugation’. He acknowledged the battle of France had been lost, but stressed that this was a world war, not a Franco-German one and that all free French should keep fighting in the name of ‘honour, common sense and the higher interest of the nation’.

He thought it was necessary to gather French troops and military equipment, as well as French production capabilities, wherever possible and declared:

‘I, General de Gaulle, am starting this national task here in England. I invite all French personnel of the Army, the Navy and the Air Force, I invite the engineers and workers specialised in armament that are currently on British soil or could get there, to join me. I invite the leaders, the soldiers, the sailors, the pilots of the French Army, Navy and Air Force, wherever they may be, to get in touch with me. I invite all the French who want to remain free to listen to me and to follow me. Long live France, in honour and independence!’

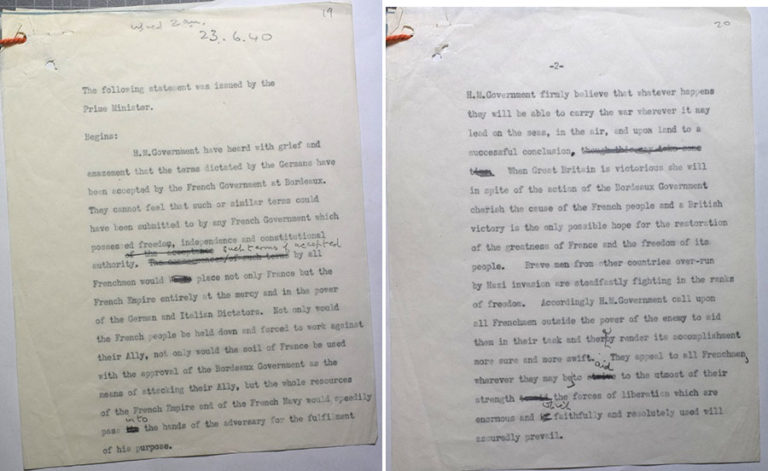

The British Government issued a statement of its own, vowing to continue the fight and calling ‘upon all Frenchmen outside the power of the enemy’ to do the same (PREM 3/174/4).

‘To all Frenchmen…’

De Gaulle was relatively unknown in France (he had been a minister for just about 11 days), and didn’t have the prestige of other generals or admirals. His ability to gather people around him was questioned and debated in Cabinet, especially after 23 June, when he informed Churchill of his intention to form a French National Committee and asked the British government to recognise it publicly. The Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs pointed out that they didn’t have much choice and that de Gaulle ‘was at least a vigorous personality’. Churchill agreed that de Gaulle ‘might be the right man’ (FO 371/24349).

In the evening of 23 June, General de Gaulle announced the formation of a French National Committee to keep on fighting. Immediately after his speech, the British Government declared they no longer recognised the French Government at Bordeaux, would support the National Committee and ‘would deal with them in all matters concerning the prosecution of the war’ (PREM 3/174/2).

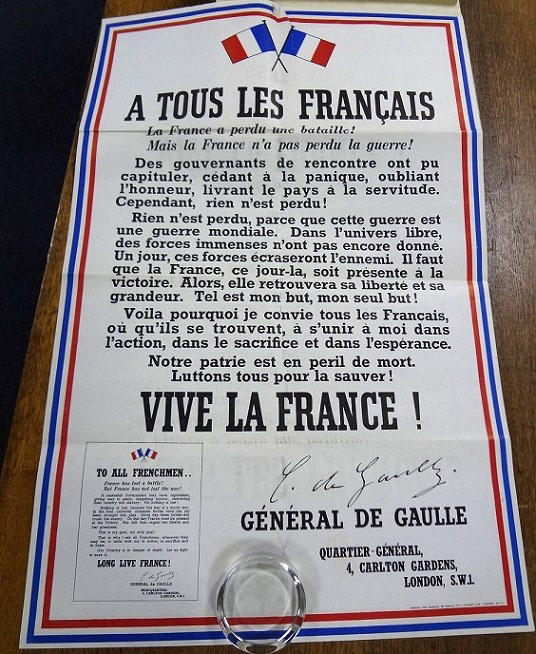

On 28 June 1940, de Gaulle was recognised as ‘the Leader of all free Frenchmen, wherever they may be, who rally to him in support of the Allied cause’. Later in the summer, posters called all Frenchmen to arms, bearing the famous words ‘France has lost a battle! But France has not lost the war!’ (FO 371/24350).

The French National Committee had been described by the French Ambassador to Britain, Charles Corbin, as ‘nothing more than a construct of the imagination’. Today, as we mark the 80th anniversary of the Appels of 18 and 22 June, and as the Légion d’Honneur was awarded to the City of London by the President of the French Republic, we celebrate this imagination. This imagination and ‘a certain idea of France’ allowed for a different narrative. This imagination enabled de Gaulle to declare on the BBC on 23 June 1940: ‘The war is not lost, the country is not dead, hope is not extinct’.

Although I am a committed Francophile (which doesn’t make me necessarily a bad person) there is no getting away from the fact that De Gaulle fought not just for France but also for De Gaulle – for example ordering Leclerc to breakaway and liberate Paris, then suggesting that the city had been liberated without Allied help and finally virtually ordering British units out of the city.

But as we are constantly discovering those in the public eye are rarely completely devils or saints.

The Franco-British Union was a remarkable proposal. In a sense it recognised the truth of the kingdoms in the Late Middle Ages, joined if in struggle across the Channel.

In 1946 Churchill also proposed a United States of Europe. One’s way of life can be preserved within a greater embrace.

The actual shape of national boundaries matter, until they don’t. What seems to be more important is the shared values and culture, especially those of regard for freedom and democratic rule of law. These are the threads that run between both countries.