Charter of the United Nations (catalogue reference: FO 93/1/263)

Today is the 70th anniversary of the first meeting of the International Court of Justice at The Hague, ‘the principal judicial organ of the United Nations’. It was set up to peacefully decide disputes between nations; as such it forms a central part of the modern system of international relations.

The settlement of disputes between countries by some form of arbitration or mediation has a long history. In the years preceding the First World War organised structures were put in place to support this, something that gained momentum after the war with the foundation of the League of Nations.

As part of the League of Nations, the Permanent Court of International Justice was set up to provide a regular and continuous space where the disputes between nations could be resolved peacefully.

Events around the world in the 1930s and the outbreak of the Second World War left the reputation of the institution in tatters, but many still saw judicial settlement as the best way to avert further conflicts.

Palace of Peace (image source: Wikicommons)

With this in mind in the British government began, in late 1942, to discuss what a new court would look like and how it would fit in the new world order. The American government proved unwilling to discuss the matter, something the Foreign Office decried as ‘very short-sighted’ (FO 371/31000). Despite this the British put together an international committee under the chairmanship of Sir William Malkin, Chief Legal Advisor to the Foreign Office, to draft proposals for the formation of a new court.

Charter of the United Nations (catalogue reference: FO 93/1/263)

In August 1943 Malkin wrote a memorandum on the future of a ‘World Court’. He was, in truth, candid about the limitations of the work of any future court:

‘It is no doubt possible to exaggerate the part which the judicial settlement of international disputes can usefully play in the world order, and I think that this was done to some extent in the period between the two wars. It is also possible to make the mistake of attempting to deal by judicial machinery with what are really political questions, and in this sense I should agree that “the only matters likely to be referred to a World Court with any hope of success would be matters of no political importance.”‘ (CAB 66/40/21)

Despite Malkin’s concerns the British were very keen to pursue the idea of an international court. This was given further momentum by the ‘Declaration of Four’ made by the United States, Britain, the USSR and China in October 1943. This stated that those powers:

‘recognise the necessity of establishing at the earliest practicable date a general international organisation, based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all peace-loving states, and open to membership by all such states, large and small, for the maintenance of international peace and security.’ (FO 93/1/252)

Within this it was clear that a new world court would be essential. In 1944 the committee formed under Sir William Malkin reported, and this text formed the basis for the British position at the discussions on the shape of the new court which were held in Washington in April 1945. These discussions were carried forward into the San Francisco Conference, which drew up the United Nations Charter. The Charter set out that ‘The International Court of Justice shall be the principal judicial organ of the United Nations’ and the court’s statute formed ‘an integral part of the present Charter.’

The statute made it clear that ‘only states may be parties in cases before the court’ and ‘the jurisdiction of the Court comprises all cases which parties refer to it and all matters specially provided for in the Charter of the United Nations or in treaties and conventions in force.’ In effect, the court was to become the final arbiter in disputes between nations (FO 93/1/263).

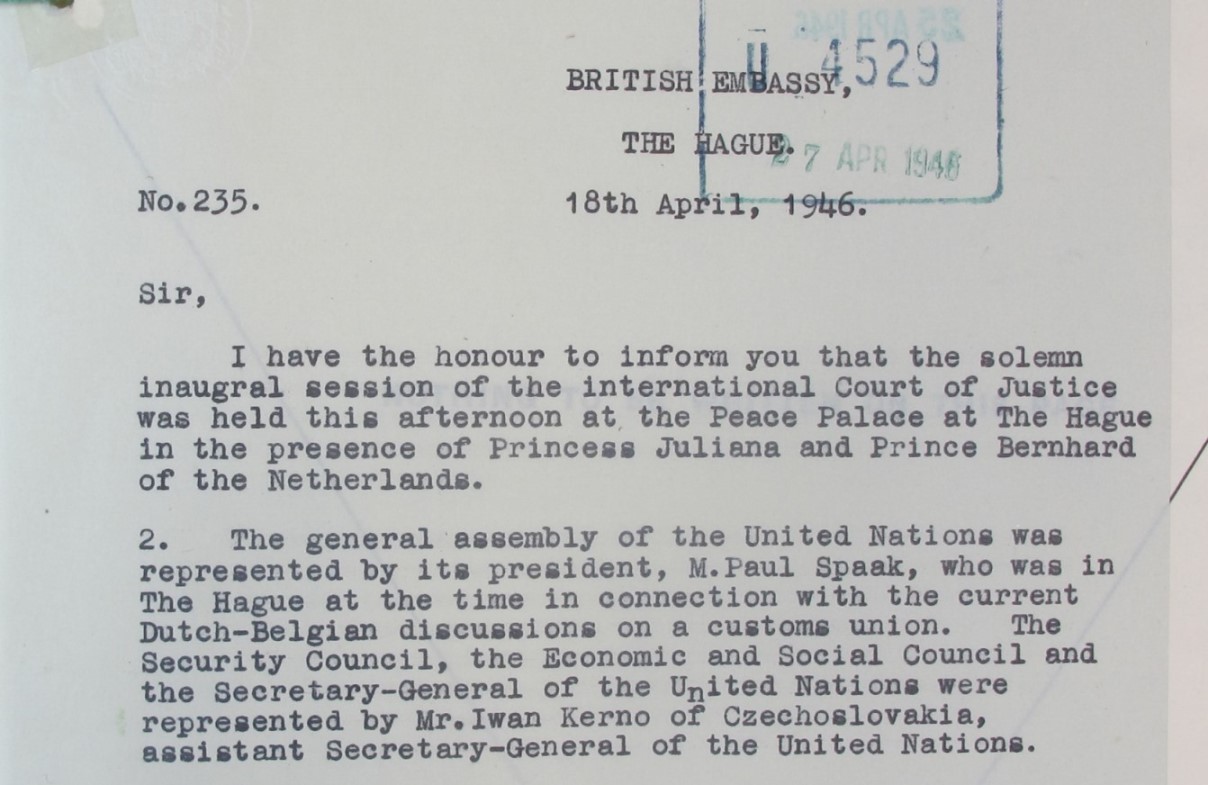

Letter from John Lambert to Ernest Bevan (catalogue reference: FO 371/57112)

70 years ago today the court sat for its inaugural session in the Palace of Peace, built by Andrew Carnegie at The Hague. As John Lambert, Secretary to the Embassy at The Hague, reported, ‘the ceremony was efficiently and impressively conducted and in simplicity and dignity was worthy of the historic nature of the occasion’ (FO 371/57112).

The first case heard by the court was brought by the British government against Albania over the laying of mines in the Corfu Channel. Since then the court has heard a further 160 cases and remains the final resort for judicial settlement between nation states.

Spelling mistake …should be PRINCIPAL ….ahem….

Thank you, I’ve updated that mistake.

Best,

Nell

More power!