Today, we are releasing new FCO 33 files for 1990, a large number of which relate to the German Unification. These files complement those already available in the PREM 19 and CAB 128 series.

Some of these documents have been published as part of the excellent DBPO volume on German Unification 1989-1990, but some I had never seen before. Taken together they make for excellent reading and give a fresh insight into one of the most momentous events of the 20th century.

Here are a few highlights.

‘The sound of 1989’

Writing at the beginning of 1990, the British Military Authorities in Berlin gave a colourful account of the events of 1989. They had been trying to promote Western values (which, incidentally, involved setting up ladders on the bank of the Spree ‘to help people who found themselves in the water to climb to safety’), and were very happy to report this era now belonged to history. They noted:

‘To have contributed to the establishment of a Berlin “whole and free” which stands as a symbol of international cooperation and the triumph of Western values would be an important achievement of British post-war policy’.

There had been momentous events in 1989, the review states, and one of them took place on 22 December when

‘under pouring rain, leaders from both German States and from both parts of Berlin spoke together at the Brandenburg Gate and the crowds poured through in both directions in a never-ending stream. Again, a British military band, together with its goat mascot, was on hand to bring colour and life to the waiting crowd’.

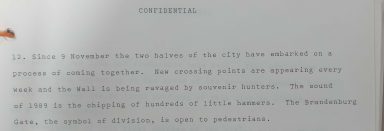

The review also mentions the Wall, or, rather, its dismantling at the hand of eager collectors (don’t we all have a piece of the Berlin Wall?):

‘Since 9 November the two halves of the city have embarked on a process of coming together. New crossing points are appearing every week and the Wall is being ravaged by souvenir hunters. The sound of 1989 is the chipping of hundreds of little hammers’ (FCO 33/10892).

- Berlin annual review for 1989 (catalogue reference FCO 33/10892)

- Berlin annual review for 1989 (catalogue reference FCO 33/10892)

‘Fresh worries piling up fast’

In February 1990, Margaret Thatcher met with former French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. Discussing the situation in Germany, she said ‘that we had entered the last decade of the century with high hopes. But fresh worries were piling up fast’ (FCO 33/10998).

And it is true that the situation was extremely fragile and volatile. Many different issues arose from the possible unification of Germany, from the border with Poland, to a monetary union, from social security and health to very complicated legal questions linked to Germany’s membership of NATO.

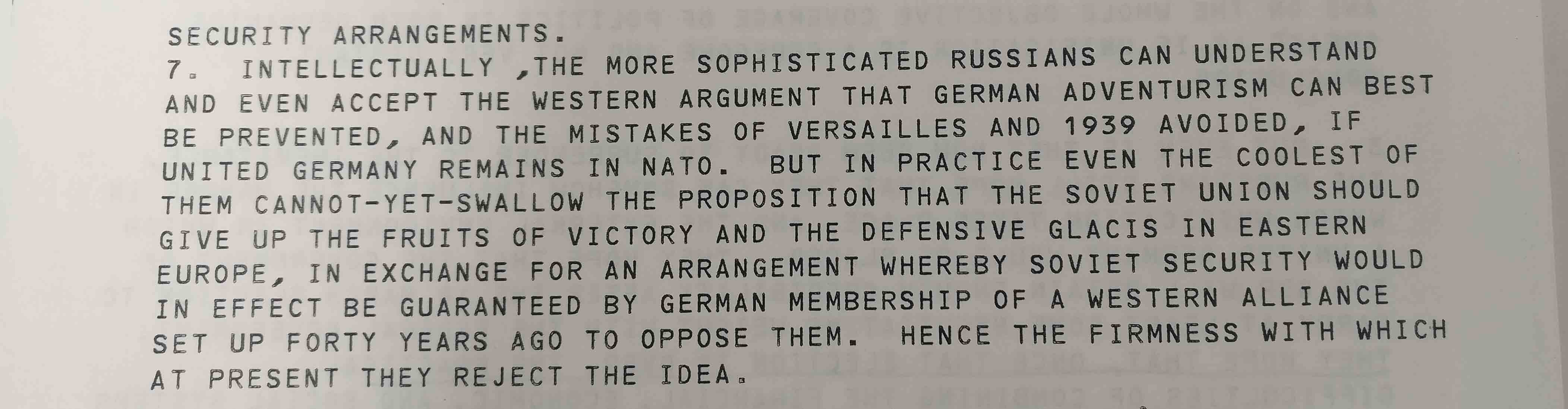

The NATO issue was a particularly difficult one, and not only because the Soviet Union was staunchly opposed to a unified Germany being a full member. The Soviets understood the logic behind the desire for Germany to remain in NATO, but

‘in practice even the coolest of them cannot-yet-swallow the proposition that the Soviet Union should give up the fruits of victory and the defensive glacis in Eastern Europe, in exchange for an arrangement whereby Soviet security would in effect be guaranteed by German membership of a Western Alliance set up forty years ago to oppose them’ (FCO 33/10899).

There were probably misunderstandings on all sides and a lot of it came down to perceptions. On 20 February, Sir Michael Alexander, of the UK Delegation to NATO, explained:

‘The German authorities are, as everybody here recognises, engaged in a singularly complicated operation. But it does not help the situation that they have succeeded (in the words of Odeja (Spain)) in giving the impression that they do not wish to take account of the views of the rest of the Alliance. They will have to work hard to remove that impression’ (FCO 33/10898).

In reality, Helmut Kohl did understand the necessity of taking into account the sensitivities of the rest of the Alliance, and the need for an ‘orderly process for change’, but, he told the British Ambassador to West Germany Christopher Mallaby,

‘his request to [Britain] was that we should not misunderstand the psychology of the Germans: they were not over the top nationalists, but were happy, as any normal people would be, at the prospect of unity’ (FCO 33/10895).

‘Britain’s public standing in Germany is at its lowest for years’

It probably didn’t help that, Margaret Thatcher and Helmut Kohl didn’t get on at all. British and German ideas were sometimes rather close or, at least, not diametrically opposed, but personalities definitely got in the way.

At the State Department, Robert Zoellick

‘said he found the language used by Chancellor Kohl and Mrs Thatcher about each other very distressing and even embarrassing. The Americans did not regard Kohl as an intellectual giant or their ideal choice as a dinner guest. But they had a decent respect for him and he was the head of government of an important ally’ (FCO 33/10893).

The general perception in Germany was that ‘Mrs Thatcher [would] do everything possible to fight German unity’ (FCO 33/10895). Margaret Thatcher was worried that things were going too fast, and wanted a proper structure to assess the political and legal consequences of unification, but the language she used on several occasions made it very difficult for diplomats in Britain and Germany to assert that the UK was wholly supportive of unification. The Prime Minister’s reservations were causing ‘growing resentment’ in Germany, and costing Britain its influence and weight in the ongoing negotiations. On 22 February 1990, Mallaby reported ‘Britain’s public standing in Germany is at its lowest for years’.

This caused a bit of a rift between Margaret Thatcher and her diplomats. Douglas Hurd, the Foreign Secretary, thought that Britain should be very cautious ‘not to appear to be a brake on everything’ and ‘should come forward with some positive ideas of [her] own’ (FCO 33/10998), but he had very little leeway. In the end, even though she eventually came to terms with the unification of Germany, the Prime Minister’s ‘strength of feelings’ cost Britain much time and prestige.

‘A day of joy for all Germans’

Despite all the legal and political hurdles, Germany was finally reunified on 3 October 1990. When the final decision was made on 23 August, Helmut Kohl declared at the Bundestag that it was ‘a day of joy for all Germans’ (FCO 33/10943).

The Treaty on final settlement was signed in Moscow on 12 September, and the Declaration suspending the operation of quadripartite rights and responsibilities was signed in New York on 1 October.

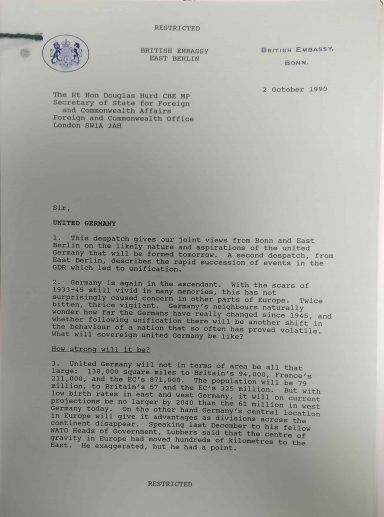

On 2 October 1990, Patrick Eyers, the Ambassador to East Germany, filed his final despatch, ‘farewell to an unloved country’, and wrote:

‘At midnight to-night the German Democratic Republic will cease to exist as a State (…). In what mood do the people of the GDR come to unity? (…) My impression is one of deep emotion, of contentment mixed with a certain trepidation in the face of the uncertainties ahead. But none of them is looking back’ (FCO 33/10706).

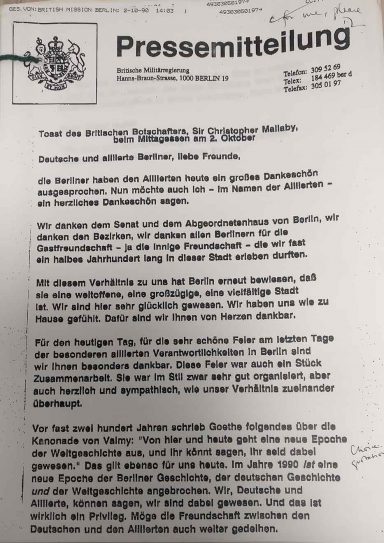

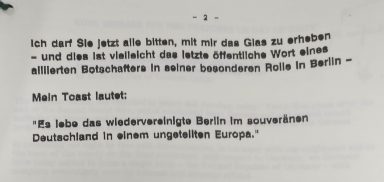

Around the same time, Mallaby was toasting Germany and Berlin over lunch. Thanking the German people, he raised his glass and said: ‘long live reunified Berlin in a sovereign Germany, in an undivided Europe’.

At the FCO, Hugh Salvesen commented: ‘a good little speech – but it’s a pity it was issued on Britische Militarregierung stationery…’ (FCO 33/10944).

- Mallaby’s speech, 2 October 1990 (catalogue reference: FCO 33/10944)

- Mallaby’s speech, 2 October 1990 (catalogue reference: FCO 33/10944)

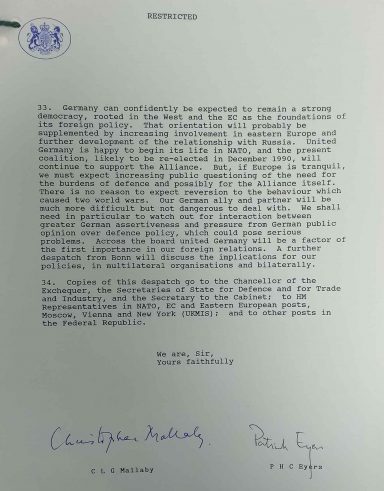

Eyers and Mallaby also filed a joint despatch entitled ‘United Germany’, looking at what ‘sovereign’ and ‘united’ Germany would be like. Their conclusion was very clear: ‘Our German Ally and partner will be much more difficult but not dangerous to deal with’.

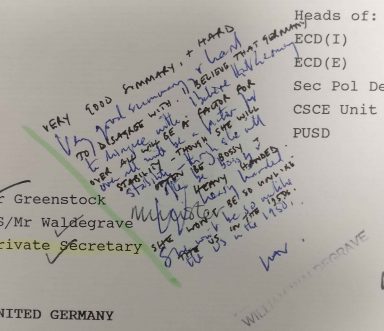

At the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, William Waldegrave concurred:

‘Very good summary, and hard to disagree with. I believe that Germany overall will be a factor for stability – though she will often be bossy and heavy handed. She won’t be so unlike the US of the 1950s’ (FCO 33/10944).

- ‘United Germany’, 2 October 1990 (catalogue reference: FCO 33/10944)

- ‘United Germany’, 2 October 1990 (catalogue reference: FCO 33/10944)

- Waldegrave’s comment on ‘United Germany’ (catalogue reference: FCO 33/10944)