The concept of a trade union, or a body of workers joining together to protect their own interests, has a long history stretching back to the Middle Ages. These associations attempted to protect the employment of their members through controlling wages, working hours, the admission of apprentices and the standardisation of working practices[ref]Catharina Lis and Hugo Soly, ‘An Irresistible Phalanx: Journeymen Associations of Western Europe 1300-1800’, International Review of Social History, 39 (1994), pp. 11-52, (pp. 24-5)[/ref]. Associations such as this have always been problematic for successive governments, and as early as 1549 it was made illegal for groups, ‘confederacies or conspiracies’ of workers to determine rates of pay or the amount of work to be done in a given time[ref]Ibid., p.27[/ref].

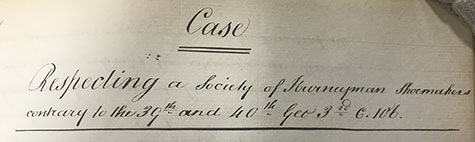

Extract from the Treasury Solicitor papers relating to the prosecution of Ladies Shoemakers under the Combination Laws, 1820. Catalogue reference: TS 25/2035

Towards the end of the 18th century the Industrial Revolution had caused even greater numbers of skilled workers to ‘combine’ in order to protect their interests, with the rise of mechanisation and automation across rural and urban trades[ref] Norman Lowe, Mastering Modern British History, 5th ed. (London: Palgrave, 2017), p. 251[/ref]. In an attempt to prevent any revolutionary movement from these organisations, trade unions were made illegal in 1800 under the Combination Laws. The Combination Laws, introduced by William Pitt, made it illegal for workers to form any combination ‘for obtaining an Advance of wages […] or for lessening […] their Hours of working’[ref]Ibid., p.252[/ref].

For radicals like Francis Place and their supporters in Parliament, including Joseph Hume and Sir Francis Burdett, these laws were not only crude reactionary hangovers from the war with France, when such associations were viewed with particular suspicion, they were also ineffective. Trade unions, or combinations, still existed in all but name, most calling themselves ‘friendly societies’. Making them illegal only caused resentment. What is more, some labourers found themselves compelled to join a society, as the 1820 case of Samuel Starling and James Mills illustrates.

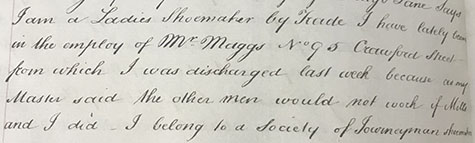

Samuel Starling, a ladies’ shoemaker, confessed that he had belonged to a ‘society of townsmen’ while he had worked in the employ of Mr Maggs. However, he explained:

I was discharged last week because my master said the other men would not work with me […] if I didn’t belong to a society of Journeymen Shoemakers […] I entered it about two years ago because my fellow workmen at the shop where I was employed said I should not have work if I did not belong to the society[ref]Catalogue reference: TS 25/2035, ff. 574-580[/ref].

Starling then goes on to detail how the society worked, describing how they met once a fortnight at 8 o’clock on Monday evenings. At each of these meetings a subscription fee of 3d. was payable from each member, along with covering the cost of a pot of beer, which was to be drunk ‘for the benefit of the health of members who did not attend’[ref]Ibid.[/ref]. However, it appears that Starling got behind with his subscription fees and ended up owing the society 5s. 3d. for which he was struck off from its membership. As a direct result of this, he then lost his job[ref]Ibid.[/ref].

Testimony of Samuel Starling from Treasury Solicitor papers relating to the prosecution of Ladies Shoemakers under the Combination Laws, 1820. Catalogue reference: TS 25/2035

Starling’s position appears particularly precarious: not only does he claim to have been pressured into joining the society in order to get work, and therefore breaking the law, but when he could no longer afford to belong to the society he was turned away from the society and found himself unemployed.

Starling was then questioned further about the operations of the society, about which he appeared to know very little:

I don’t at all know how the funds are applied – nothing that I ever heard was given to a member in case of sickness except perhaps to a favoured member. If there is a strike for work, I suppose there would be some support for a short time[ref]Ibid.[/ref].

The answers given by Starling indicate the type of subversive activity the government was trying to crack down on – namely organising and supporting strike action among workers.

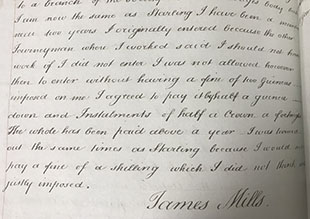

The testimony from James Mills followed. Mills was also a ladies’ shoemaker previously in the employ of Mr Maggs. Mills was turned out of the society and Mr Maggs’ employ at the same time as Starling because he would not pay a fine of a shilling, which he believed had not been ‘justly imposed’[ref]Ibid.[/ref].

Testimony of James Mills from Treasury Solicitor papers relating to the prosecution of Ladies Shoemakers under the Combination Laws, 1820. Catalogue reference: TS 25/2035

The outcome of this particular case was that both Starling and Mills were found guilty of an offence against the Combination Laws[ref] Ibid.[/ref].

Starling and Mills’ predicament was not unique, being caught between being a member of a potentially illegal society and forced to pay its fees or risk unemployment. In this unfortunate case, both Starling and Mills not only racked up debts to their society and lost their jobs, but they were also found guilty of being a member of an illegal association under the Combination Acts. The usual punishment for this crime was either two months imprisonment or three months hard labour.

It took a further four years before an inquiry was set up to investigate the Combination Laws. The convincing evidence given by the workers interviewed as part of this process played a significant part in their repeal. However, industrialists were horrified by this turn of events as hundreds of trade unions came out into the open, and hundreds of new organisations were formed.

Following the repeal of the Combination Laws, this proliferation of new unions led the government to institute the Amending Act of 1825, which clarified that while trade unions could exist and negotiate about hours of work and wages, they were not able to obstruct or intimidate[ref]Lowe, pp. 21, 252[/ref].

Labour unions, like all human organizations can suffer from corruption, but that does not mean they are all corrupt. Regarding the problem of individual workers not wishing to follow trade union rules, like closed shop, means that the main tool of unionized workers, the strike, will not be effective, so closed shop is something that union members need to accept if their union is to have the power to negotiate successfully with the employer