April this year marks the 700th anniversary of the so-called Declaration of Arbroath, a seminal document and artefact in the history of Scottish independence and Anglo-Scots relations.

Once described as Scotland’s Magna Carta by Professor Archie Duncan, the document was drawn up in 1320 against the backdrop of the Wars of Independence, recently brought to life in all its gory detail in Netflix’s ‘Outlaw King'[ref]A A M Duncan, The Nation of Scots and the Declaration of Arbroath (1320) (London: The Historical Association, 1970), p. 174.[/ref].

The Declaration takes the form of a letter sent from the nobles and barons of Scotland to the Pope, asking for John XXII to recognize Robert Bruce’s claim to the Scottish throne and Scotland’s sovereignty as a kingdom. The latter had been under scrutiny from the 1290s when Edward I sought overlordship of Scotland in exchange for his arbitration of claimants to the Scottish throne, sometimes called ‘The Great Cause’. Edward was invited by the community of the realm of Scotland to arbitrate between multiple claimants (including Bruce’s grandfather) after the deaths of King Alexander III in 1286 and of his daughter Margaret, the ‘Maid of Norway’ in 1290[ref]The Great Cause was a crisis of the Scottish monarchy in the early 1290s. After the death of Alexander III, the only heir to the Scottish throne was his granddaughter Margaret, daughter of the king of Norway. But on the way to Scotland to claim the throne the infant had died, leaving a contested throne. Edward I was invited by the guardians of the Scottish realm to arbitrate, choosing John Balliol in exchange for overlordship in November 1292. The National Archives actually holds many records surrounding ‘The Great Cause’ in our collection, such as E 39/18 or the first entry of C 71/1.[/ref]. John Balliol was chosen to be king in exchange for doing homage to Edward as ‘Lord Paramount’.

The terms of this agreement soon became intolerable to the Scots and Balliol went back on his homage, rebelling against the English and leading to Edward’s invasion. The divided factions of Bruce and Balliol refused to unite even in the face of this threat, and Balliol abdicated in July 1296. The English king from this point directly ruled Scotland against the Scottish rebels.

For the English kings, Edward I to 1307 and his son Edward II thereafter, recognizing Bruce as a monarch meant denying their own claims of authority and relinquishing the de facto leadership they had assumed after Balliol’s abdication.

By comparison, the papacy objected on more moral grounds. In 1306 at the Franciscan friary church in Dumfries, Bruce had murdered his rival to the Scottish throne, John Comyn, a kinsman of John Balliol. To murder a fellow Christian on sacred ground was a grave sin. Bruce was excommunicated for this crime, damning his immortal soul.

In 1317/18, the papacy also placed the people of Scotland under an interdict for their continual support of Bruce and warfare against the English. The interdict meant that religious rites or services could not be performed, and many church livings could not be filled by new clergymen, jeopardizing their souls and access to salvation. In practice, the Scottish clergy ignored this order, but the Scottish Crown was under increasing diplomatic pressure and papal censures limited opportunities to make alliances. The Declaration was created in this climate and aimed to alleviate these pressures.

A contemporary copy of the Declaration is held by the National Records of Scotland, which is currently on display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh to commemorate the anniversary. The National Archives holds many records of military, territorial, economic and diplomatic dealings in Scotland, as a result of England’s enduring claims of authority in the 1300s. This includes documents from 1320 which can provide insight into Anglo-Papal relations in the year the Declaration was created and into the diplomatic struggle between two kingdoms.

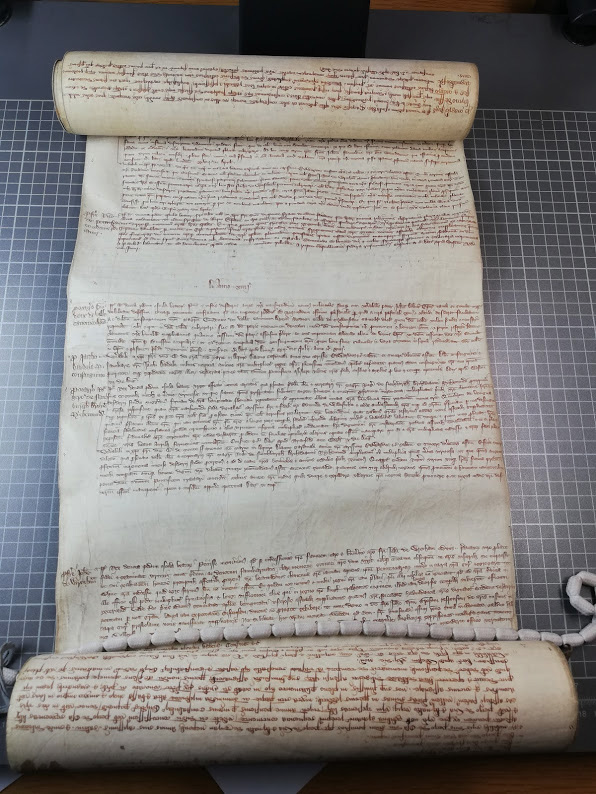

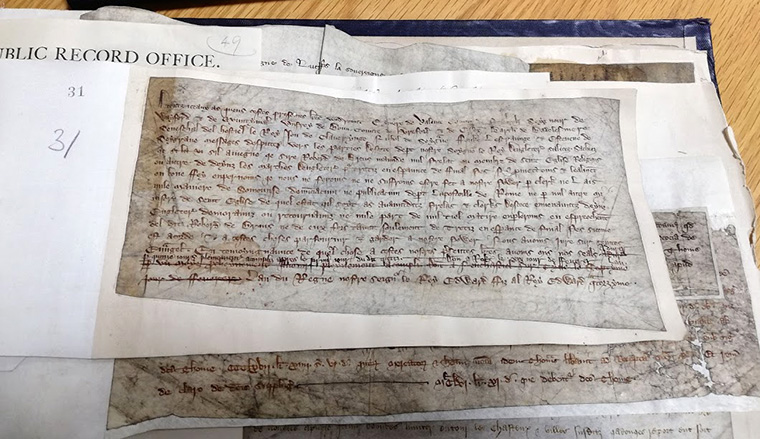

The two principal sources for Anglo-Papal relations for this period are the Roman Rolls (C 70) and the Papal Bulls (SC 7), which show the correspondence between the papacy and the English Crown. The Roman Rolls record outgoing letters, often abbreviated and copied onto long membranes of parchment, sewn head and foot (chancery style) for the purposes of record-keeping, and each roll can cover a year or number of years[ref]For more information, please see the guide to C70 here, or Barbara Bombi, ‘The Roman Rolls of Edward II as source of administrative and diplomatic practice in the early fourteenth century’, Historical Research, 85 (2012), 597-616.[/ref].

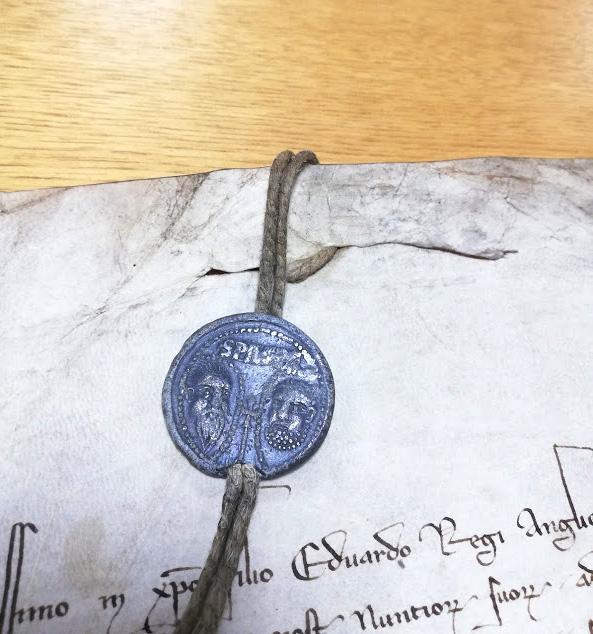

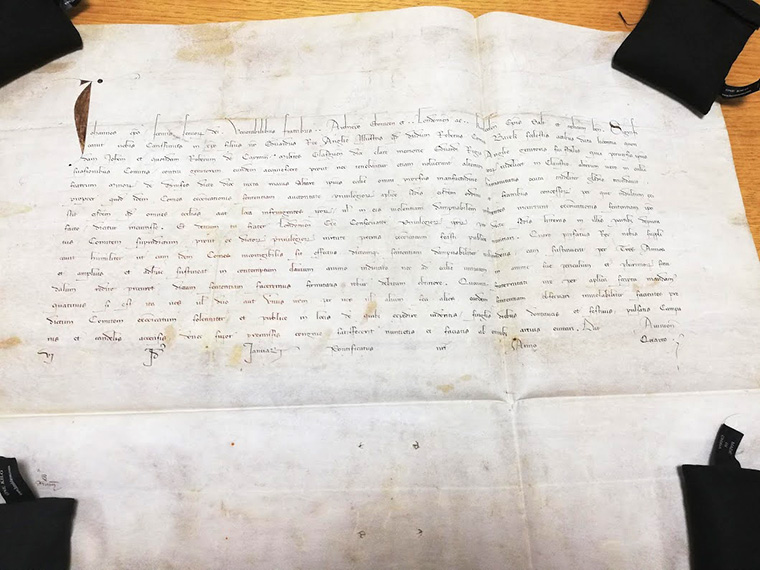

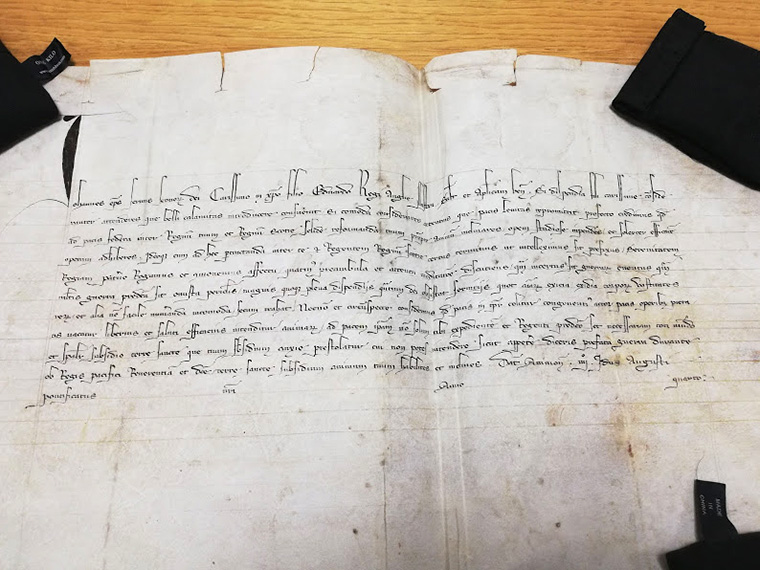

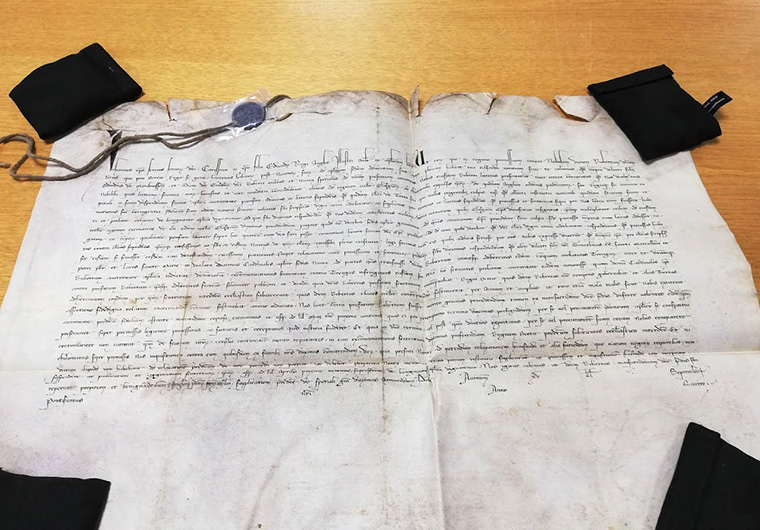

The Special Collections series of Papal Bulls are original letters – known as ‘bulls’ as they are authorized by the attachment of a small lead seal bearing, on one side, the name of the pope and, on the other, an image of the bearded Saints Peter and Paul – sent from the papacy to the English Crown. For the year 1320, three papal bulls survive which refer to Robert Bruce and a single Roman Roll which covers the years 1317 to 1321.

The first reference to Robert Bruce in the English records for 1320 appears to have been a papal bull addressed to the archbishop of York, William Melton, and the bishops of London and Carlisle, sent on 8 January. Pope John XXII requested that these leading churchmen publish the sentence of excommunication against Bruce and apply greater pressure upon his government. Oddly, Robert is incorrectly described as Robert earl of ‘Barek’, rather than Robert earl of Carrick (his title before being crowned king).

The bull recounts the murder of Robert and John ‘Caymin’ in detail, referring to the church of the Greyfriars in ‘Dymfes’ or Dumfries, reports that Bruce ‘crudeliter gladio trucidavit’ or cruelly slaughtered the man with a sword. The pope’s language was particularly damning and demonstrates that Bruce’s crimes remained unforgiven.

Letters from the English perspective, recorded on the Roman Roll, also cultivated a negative depiction of the Scots. On 12 January, Edward II requested the transfer of the English clergyman William Cassalen to the diocese of Ossory in Ireland because of the ‘hostiles et inopinatos agressus scottorum’ or the hostility and unexpected attacks of the Scots in his temporalities. This was undoubtedly a reference to the recent invasion of Ireland between 1315 and 1318 led by Edward, younger and only surviving brother of Robert Bruce, where the Scots brought fire and sword deep into southern Ireland without landing a decisive blow against English administration in Ireland.

Another entry from 13 March similarly asks the pope to continue opposing ‘rebellionem et obstinatam malitiam scotorum’ or the rebellion and stubborn malice of the Scots. This kind of inflammatory language was to be expected from the English Crown who were trying to ensure the pope’s continued support against the Scots and justify their own claims of overlordship. It was increasingly employed throughout the 14th century and has been linked by some historians to the formation of national identities[ref]Andrea Ruddick, English Identity and Political Culture in the Fourteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).[/ref].

Although the Declaration had been sent around April, there were many delays before the pope received the letter[ref]Sir James Fergusson suggested this may have been a result of ‘adverse weather’, ‘danger of English ships’ or that it took time to gain an audience with the Pope at the papal court: J. Fergusson, The Declaration of Arbroath (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1970),p. 25. [/ref]. James Fergusson and Grant Simpson suggested they did not actually receive the Declaration until some point between 16 June and the 29 July[ref]Fergusson, p.26. Grant Simpson, ‘The Declaration of Arbroath Revitalised’, Scottish Historical Review 56, 161, Part 1 (1977), 11-33 (pp. 20-21).[/ref]. We know, at least, that the English king had not received news about the document before 25 June, when he wrote to the pope requesting the appointment of Richard of Pontefract to the bishopric of Dunblane in central Scotland to exert further pressure upon the Scottish Church.

A flurry of activity at the papal court (the Curia) seems to have begun in August when Edward was sent two further letters pertaining to Robert Bruce and the Anglo-Scots war. This time the papacy requested peace and the opening of negotiations, just as they had done in 1317. The attempts of 1317 had been motivated by English interests to relieve the siege at Berwick, ultimately captured by the Scots in April 1318, but Bruce had ignored these requests and Scotland had been placed under the interdict as a result.

Calls for peace in August 1320 were markedly different because they were motivated by Scottish interests laid out in the Declaration. A letter from 10 August, which informed the English king about the arrival of Scottish envoys to the papal court, even seemed to reuse phrases directly from the Declaration[ref]Catalogue ref: SC 7/25/29. This is the same text which is found in A Theiner, Vetera Monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum Historiam Illustrantia (Rome: Typis Vaticanis, 1864), no. 430, which was used by Fergusson to identify similarities between the English papal bull and the Declaration (Fergusson, The Declaration of Arbroath, p. 26). [/ref].

In both this letter and the second from 18 August, the papacy struggled to mediate the issue of Bruce’s title. In the first, he was simply identified as ‘regentem regnum Scotie’ or he who rules the kingdom of Scotland. While in the second he was called ‘nobilem virum Robertum dictum Brus qui pro Scotie Rege’ or the nobleman Robert called Bruce who calls himself king of Scotland.

The issue of Bruce’s title was something the Declaration had sought to address and correct. A few years earlier, Bruce’s reason for rejecting the presence of papal legates was because their letters did not correctly address him as king of Scots. This careful phraseology of his title hints at these past issues and highlights the papacy’s careful mediation of Bruce’s title when addressing the English king.

Mediation seems to have begun at this period and continued throughout the rest of the year, into 1321. The Roman Roll mentions arrangements being made for a peace treaty as early as 11 November. These negotiations seem to have been a sincere effort to end the ongoing war as internal struggles began to emerge in both kingdoms. Aymer de Valence, earl of Pembroke, and other English envoys are recorded as granting safe-conducts to Scottish clergymen hoping to enter England in February 1321. The aim of this was to negotiate a ‘final Pes’ or final peace between Bruce and Edward II.

Similarly, the Roman Roll describes plans for Scottish ambassadors to travel to the papal court in April 1321 to further these discussions. There seems to have been a real desire from the English at this time to put an end to the war, begun nearly 25 years before.

However, peace would prove elusive and was not achieved until the short-lived ‘shoddy’ peace of Edinburgh-Northampton in 1328, negotiated by Bruce’s envoys and representatives of the new king, the teenage Edward III, who was heavily under the influence of his mother Queen Isabella and her possible lover, Roger Mortimer.

The documents briefly discussed here, alongside others also held at The National Archives, can help to broaden our understanding of 14th-century diplomacy and shed important light on the English perspectives to the Declaration of Arbroath.

Jenny McHugh is a PhD student at Lancaster University researching loyalty and identity during the Second War of Scottish Independence (1332-1357). She undertook a placement at The National Archives for six weeks in January and February this year, which was funded by the generosity of the Royal Historical Society and the Scottish Historical Review Trust.

The copy of the Declaration is not on display at the National Records of Scotland due to the Coronvirus crisis, see https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/news/2020/declaration-of-arbroath-display-postponed

The Declaration of Arbroath is a wonderful document outlining the need for a continued homeland for the Scots. It’s real importance is to the world at large as it establishes and reinforces the need for a homeland for all groups of people free from conquest by foreign powers.

Now, if the Scots could declare themselves free from the SNP and the self-imposed suppression that comes from within Scotland and regain their heritage free from fear of being racist or whatever other label is used to guilt Scots into not being Scots.