It is a thoroughly unremarkable occurrence to see a letter in The National Archives addressed ‘To my most loving brother’. Literally thousands of pieces of correspondence bear some version of this rhetorical commonplace. Only one, however, does so in Irish.

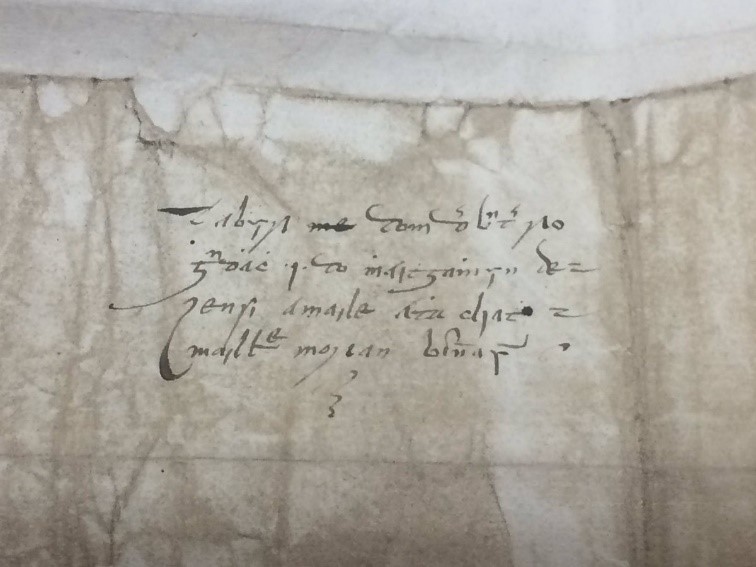

Writing in 1618, Brian Coghlan of King’s County – present day Offaly – addressed a letter to the German colonial adventurer Mathew de Renzi with the endorsement ‘Tabuir dom dearbratear ro gradhach .i. do mhaithgamhuin de rensi a maile atha cliath maille re (?) moran bEnnacht’, which we might translate as ‘Give to my most loving brother .i. to Matthew de Renzi in Dublin with many blessings’.

Brian Coghlan writing to Mathew de Renzi. WALE 31 7

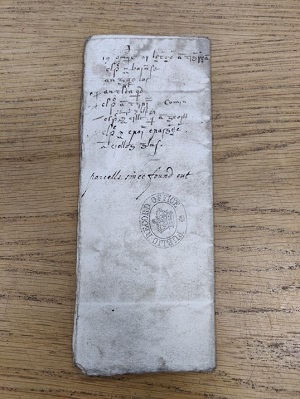

The endorsement came to the attention of archivist Dr Daniel Gosling while working to catalogue a cache of documents related to early seventeenth-century land disputes in the Irish midlands, principally in County Offaly. It was not the first Irish language discovery in the WALE 31 cataloguing process, however. A few months prior the world had been introduced to some mysterious text on the outside fold of a small, folded petition.

Mysterious text on a small, folded petition. WALE 31 7

Keen to spread word of the discovery, and to crowdsource its transcription and translation, Dr Paul Dryburgh posted images on Twitter. These came to the attention of the present authors courtesy of Dr Neil Johnston, who looped us into the conversation given our association with a collaborative project that promotes the reading of Early Modern Irish, Léamh.org. The text turned out to be the names of townlands contested in a dispute pitting de Renzi and members of the local elite family of the MacCoghlans.

The dispute – traceable over dozens of petitions, letters and the like – is of immense historical value for the richness of detail it provides into land holding and settler-indigenous relations. Perhaps more interesting, still, is the light it sheds on the active role of Irish Gaelic participants in common law procedure, their links to the state, and the range of positions they took vis-à-vis the settler community. We are conditioned to think of Irish-English relations in the seventeenth century as grounded in conflict driven by imperial expansion, horrific violence, and culture destruction through ‘Anglicization’. And rightly so. But interests, affinities and alliances could cross political, religious and ethnic lines, Coghlan’s letter to ‘his loving brother’ serving as case in point.

The importance of the WALE 31 find, thus, lies less in the brief text itself but in how it puts English-language sources into conversation with Irish ones. In this way, the value of the Gaelic materials at The National Archives far outweighs their number or volume.

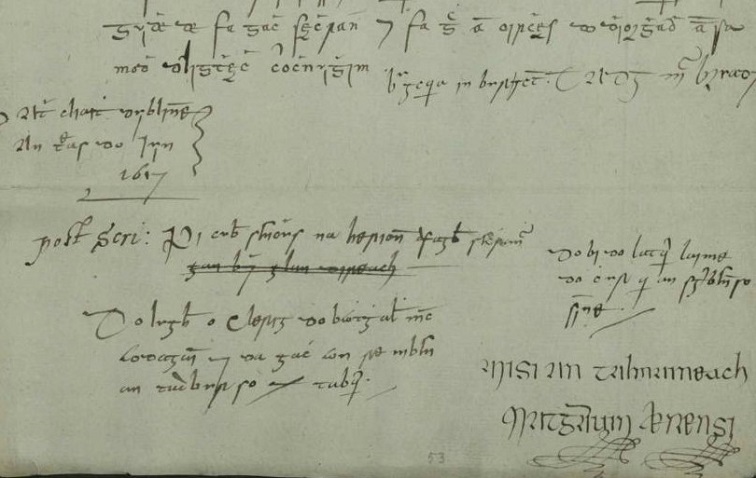

An extraordinary case in point, also drawn from the de Renzi papers [TNA SP 46/90 f. 50], is a letter from the hereditary poet Tadhg Mac Bruaideadha. Dated 1617, this is one of but a handful of extant examples of correspondence in Irish. No mere exchange of pleasantries and update on the kids, Mac Bruaideadha’s letter was an epistolary throwing of the gauntlet challenging bardic colleagues to a literary duel over the relative merits of Ireland’s northern and southern halves (Leath Cuinn and Leath Mogha, respectively). The ensuing debate, known to posterity as the Contention of the Bards (Iomárbhagh na bhFileadh), would generate dozens of poetic thrusts and parries extolling the virtues of the poets’ native regions and their historic kings while disparaging those of their rivals. Yet only the letter from Mac Bruaideadha, the sole copy of which exists in The National Archives’ holdings, gives a sense for the originating motivations and broader stakes and goals of the contest.

Drawn from the de Renzi papers, a letter from poet Tadhg Mac Bruaideadha. TNA SP 6/90 f. 50

While the primary story here concerns the manuscripts, it is worth noting the importance of the medium as well as the message. By blasting images of the Irish script on Twitter, The National Archives’ team connected to both Irish- and English-language scholarly communities.

Demonstrating the possibilities afforded by the platform, a number of scholars and online collaboratives, including Léamh, were alerted to Dryburgh’s query.

Within 24 hours, specialists in Irish history and Irish-language palaeography had come together on Twitter to work out collectively a transcription of the manuscript and the first steps toward a translation. Notable here was the way that relationships in real life translated into, and augmented, connections online, which in turn enabled real-time scholarly collaboration.

Also worth noting is how the affordances provided by social media encouraged a level of public risk-taking rarely available through more conventional means of scholarly communication (e.g. the printed book or the scholarly article). Because the tweet-and-reply framework allowed for an iterative approach to the work of transcription and translation, scholars were willing, and indeed eager, to help each other out, willing to risk getting something wrong and work collaboratively. In this way, Léamh and other online collaborations have helped nurture a loose-knit community of scholars and in a small way helped lay the groundwork for future scholarship that crosses linguistic and disciplinary boundaries.

That said, we should leave the last word to the manuscripts themselves. These documents are penned in Irish script and, with their many examples of abbreviations and contractions, reflect traditional scribal practice. Such scribal shorthand, though an integral part of the script, can make the deciphering of sources such as these a difficult task. While some of the contractions are clear enough (such as the ‘n stroke’, a single horizontal stroke above a character indicating that it is followed by the letter n), others can be more ambiguous, and a familiarity with Early Modern Irish language and grammar is often required to simply transcribe a text, not to mention translate it! This highlights the benefit of bringing together scholars from different fields – historians, linguists, experts in palaeography and manuscripts – to fully realise the potential of the archive’s Irish language sources.

There are some useful online resources for helping people to learn to read the Irish script as well: a detailed description of many common contractions and abbreviations can be found at Tionscadal na nod and the digitisation of dozens of Irish manuscripts on Irish Script on Screen has made a vast corpus of hitherto hidden material more widely accessible.

These examples from the archives afford us a mere glimpse into the wealth of Irish language material that is preserved in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century manuscripts and are a reminder of how Irish language sources can broaden our understanding of not only Early Modern Ireland, but that of England and Europe too. While the focus of Irish language scholars working on this period has been mainly on literature, and especially on Bardic poetry (which is, of course, a rich historical source in itself), these documents represent the broad range and variety of extant Early Modern Irish manuscript material, which includes petitions, letters, genealogies, prose and travel writings. Even signatures, notes, jottings and scribal marginalia, often dismissed as scribblings, can tell stories which are often obscured by more traditional sources. In the land petition above, for example, the note penned in English beneath the Irish script is a reminder of how the cultural spheres of ‘Gaelic’ and ‘English’ Ireland coexisted and cannot be understood as mutually exclusive entities, and thus reveals the complexities of relationships, cultural spheres and identities in Early Modern Ireland – topics recently explored to fascinating effect at the ‘Dominus Hibernie/Rex Hiberniae’ conference at The National Archives.

One thing reinforced at that conference is the rarity with which an Irish correspondent might address a settler colonist in the intimate terms Coghlan chose; another is that should some further linguistic treasure of the Irish past emerge in the archives, the watchful and social media savvy archivists of The National Archives will surely alert us using the 280-character epistolary conventions of our age. But what exactly is the emoji for ‘my most loving brother’?