The late 19th and early 20th century Royal Navy was an organisation, to borrow a quote, being forged in the white heat of a technological revolution. The Royal Navy was pushing the bounds of the possible with regard to submarines, fire control computers, and ship design, while Commander Henry Jackson was vying with Guglielmo Marconi to perfect ship-to-ship wireless communication.

This progress was being driven forward by a group of highly progressive and technologically-minded officers centred around Admiral Sir John Fisher, arguably the most influential officer of the era. Thus I was somewhat surprised to find a file hiding in the Admiralty records showing the considerable attention given by the Royal Navy, led in part by Fisher himself, to a far older form of technology: homing pigeons.

Photograph of homing pigeon ‘Admiral’ (catalogue reference: COPY 1/458/22)

The story began in 1893 when a young officer named Hugh Evan-Thomas drew up plans to establish homing pigeon stations at Malta and Gibraltar. Evan-Thomas is best known as the man who commanded the 5th Battle Squadron, the Royal Navy’s most powerful ships, at the Battle of Jutland, but at this stage he was Flag Lieutenant to Admiral Michael Culme-Seymour, commanding the British fleet in the Mediterranean (ADM 196/87/141). Evan-Thomas outlined how homing pigeon stations would allow British ships up to 200 miles from base to rapidly report the movements of enemy vessels. Such information he argued ‘might be very valuable’. Culme-Seymour in his covering letter to the Admiralty fully endorsed the report stating how useful such a facility would be in wartime (ADM 121/19).

Evan-Thomas quickly got Admiralty approval to begin establishing the homing pigeon station at Malta. He clearly had a background in pigeon racing and brought over a stock of his own homing pigeons. These birds were soon trained up, initially over short distances, but building up until they could cover the distance from Syracuse in Sicily, over 80 miles away, 50 of which was flying over water.

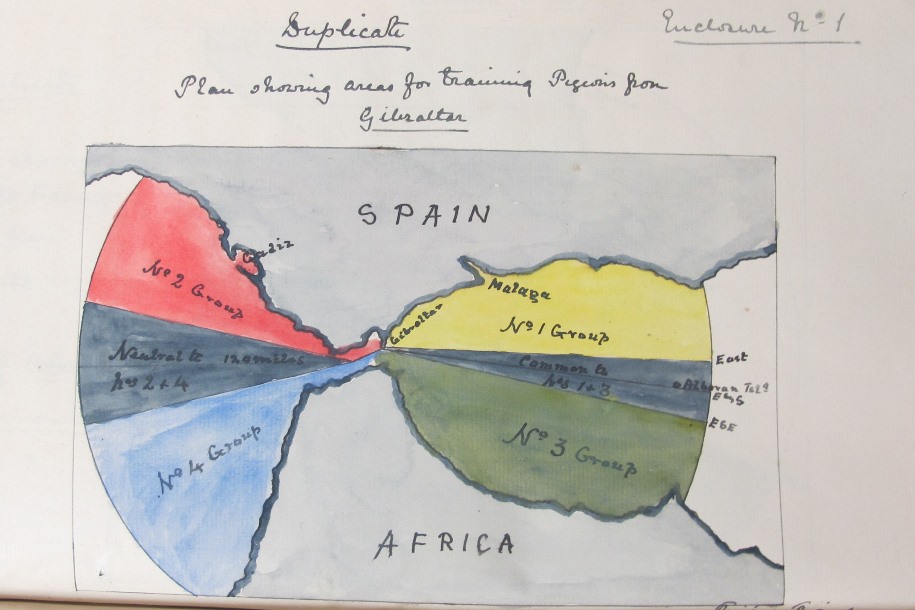

Gibraltar pigeon training zones (catalogue reference: ADM 121/19)

The pigeon service went from strength to strength over the next two years, until Evan-Thomas was called back from the Mediterranean to act as secretary to the Signals Committee. After this the standards began to slip. As Captain Henry Forbes Mackay, the fleet intelligence officer, noted the men who had taken over did not have the knowledge or the time to conduct their pigeon related duties properly:

‘(G)ood results with pigeons can only be looked for when the birds, having been carefully trained, are handled by men who thoroughly understand them.’ (ADM 121/19)

In 1899 Vice-Admiral John Fisher assumed command of the Mediterranean Fleet. As part of his thorough examination of the workings of the fleet the pigeon service came to his attention. In a report Fisher’s Flag Captain, Daniel Riddel, recommended that the Homing Pigeon Service in the Mediterranean be put on a firmer footing and that Commander Lionel Tufnell, who had run the Pigeon Service in home ports, take charge.

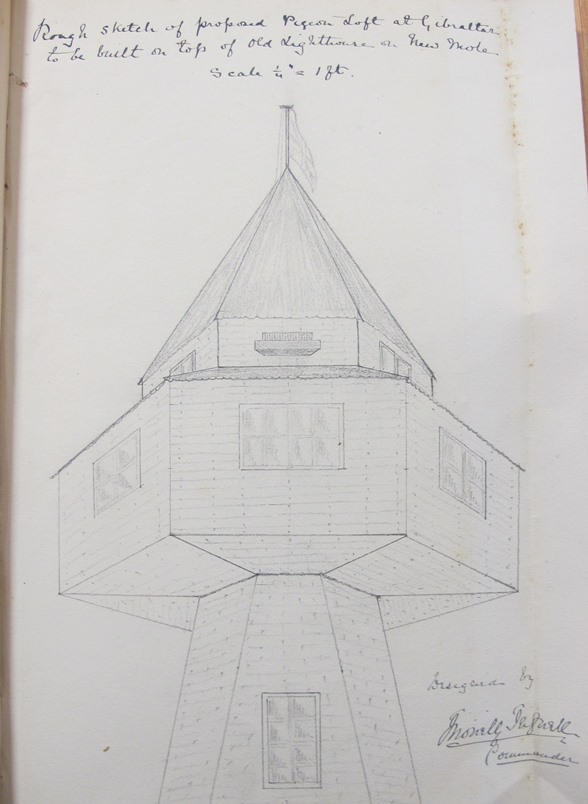

Tufnell immediately began retraining the birds and soon had the Pigeon Service at Malta up and running again. He also pressed for an expansion of the service, calling for new lofts to be established at Gibraltar, Port Said and Alexandria. Fisher took up the cause writing to Lord Cromer, British administrator in Egypt, demanding his assistance, stating how the pigeons would be of ‘immense service to us in war time’ (ADM 121/19).

These efforts soon began to bear fruit, with Tufnell able to report in May 1900 that all four pigeon lofts were established and training going well. He went on:

‘I therefore venture to state that before the end of the year there is no reason to doubt that the Pigeon Service on the Mediterranean Station will be making good progress in every respect.’

Location of pigeon loft Port Said (catalogue reference: ADM 121/19)

Tufnell’s work continued, but was overshadowed by new technological developments. In December 1899 Henry Jackson joined the Mediterranean Fleet, commanding the torpedo depot ship Vulcan, tasked with operationalizing wireless communications. The initial experiments on this front had been very successful and Jackson continued this work in 1900. By spring 1901 the results were such that the Admiralty decided that time was up for the Pigeon Service in the Mediterranean and cut off any further funding (ADM 121/19).

Pigeons were given a brief reprieve when it was realised that fitting all vessels with wireless was expensive and would take time, but by 1908 it was decided that the Naval Pigeon Service should be abolished. The birds, including over 1000 at Home Ports in Britain were auctioned off, as in the words of one Admiralty official ‘there is no strong reason why a Government Department should make a gift to the Volunteer Pigeon Fanciers’ (ADM 1/7992).

The decision did, however, proved somewhat premature: carrier pigeons made a comeback in both world wars, particularly in intelligence work. For some roles the old methods remained the best.

Thanks for sharing article with us. I will be back whenever you will add new posts. Keep posting please. good to see this.