Archival records are a window to the past quite unlike any other. Their ability to illuminate historians’ research, through direct connection to contemporary documents, means that they can provide answers which may be impossible to find elsewhere.

Although The National Archives holds over 11 million records, it is important to remember that they are from the government perspective. Therefore, it can be most fascinating to read these records against the grain, as there is much to be discovered beyond what is explicitly written.

This blog will make use of a particularly interesting case study of pit brow women in Lancashire, to explore the complexities and opportunities associated with archival work. The women’s lives can be revealed through analysis of documents from sources in the Copyright Office, and the Ministry of Power collections.

By identifying strengths and weaknesses of records, they can be analysed with greater depth and nuance, so that they are used most effectively during an exploration of the past.

The lives and work of pit brow women

The women who worked above ground at mines and collieries across the North West of England were known locally as ‘pit brow girls’. Although women were known to have taken on these roles across the country, they were an especially familiar sight in the historic county of Lancashire throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Mining at these sites was difficult, dirty and often dangerous work. As a result, the 1842 Coal Mines Act stopped all women and children under the age of 18 from working underground at collieries. This was due to fears about the health and safety of those deemed less able to withstand the harsh condition of the mines.

While in many places, this legislation marked the end of women’s employment within the mining industry, this was not the case across much of Lancashire. The Act did not forbid women from working above ground, or at what was commonly referred to in the North West as the ‘pit brow’.

Unemployment meant a catastrophic loss of financial stability for most working-class families. Therefore, these women continued a longstanding but necessary tradition of maintaining paid employment alongside their domestic role, and thus transitioned into work above ground.

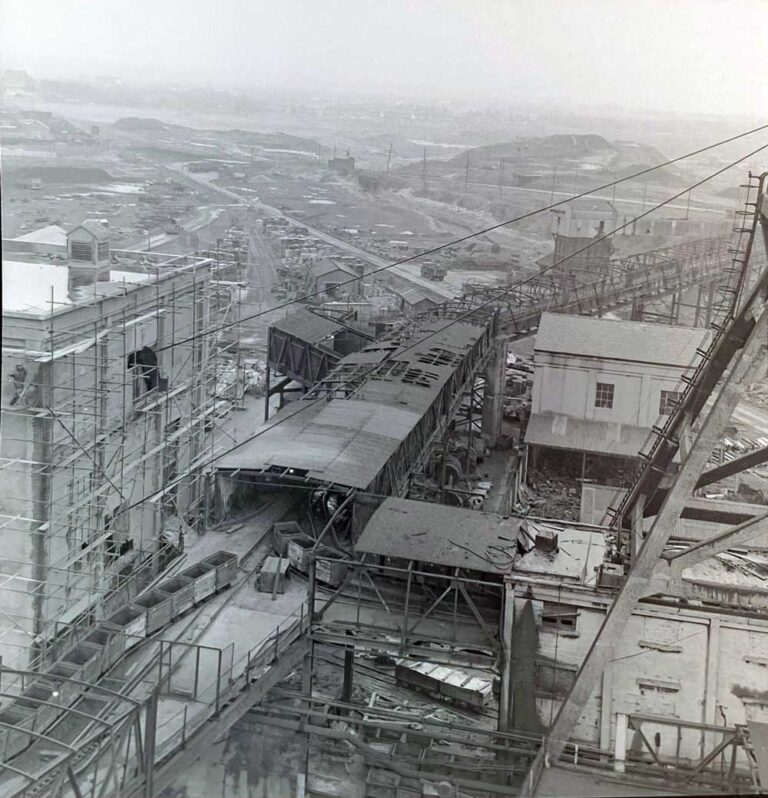

Pit brow work was far less dangerous than work at the coal face, with women’s roles mainly consisting of cleaning rocks and other debris from the coal, as well as transporting carts of coal around the site.

However, despite the fact pit brow work avoided many of the issues cited as important in the restriction of women’s work underground, it was still regarded by many to be inappropriate work for women. In order to explore why this was the case, it is important to clarify beliefs about gender roles during this period.

Women’s place in society

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, gender roles were very clearly defined, particularly amongst the upper classes. They were still also highly influential in daily working-class life, although the lines were often blurred. For women, this meant maintaining paid employment, alongside unpaid work within the home – something which was very much the case for pit brow women.

Described by Coventry Patmore as the ‘Angel in the House’, a woman was expected to prioritise her supposedly natural domestic role, rather than focusing on paid employment (see footnote 1). It is because of this belief that much of the controversy surrounding pit brow women existed, often thinly veiled by discussion of health concerns.

Sarah Edge notes that ‘the masculine outside world was one constructed in opposition to the feminine domestic space, as immoral, dangerous, dirty and corrupt’ (see footnote 2).

The middle and upper classes were especially constrained by the idea of separate spheres for men and women – men in public, and women in private. This highly normative understanding of gender roles within the upper echelons of society inevitably affected the decisions made amongst the most powerful – an important point to remember when exploring the lives of working-class women.

It is clear, therefore, that the lives of pit brow women challenged these rigid expectations. Not only was their work considered to be overly masculine (which will be discussed further), but they also subverted the stereotype of women living solely domestic lives, avoiding the male-dominated sphere of employment and public life.

The case against pit brow women

There was considerable backlash from multiple governments regarding women’s employment at collieries. There were attempts in 1872, 1886, and 1911 to restrict women’s right to employment at the pit brow. This blog will cover a range of records, connected to these three campaigns, which shared a common belief in the importance of women’s work at mines.

Government arguments consistently relied on a few key points that they deemed cause enough to prevent this work. The first was, as already mentioned, regarding women’s health, and their safety, as they were deemed too weak to cope with the exertion required within the role.

There are a variety of sources within The National Archives which reveal that these claims were, often, entirely untrue. Dr T. M. Angior, a doctor in Wigan, wrote:

‘I have been Surgeon to four separate Collieries for over 25 years, and I do not remember ever being called upon to treat a pit-brow woman for strain or any internal complication or complaint peculiar to woman, the outcome of their work’.

Appeal by the ex-Mayor of Wigan to Secretary of State to vote against amendment prohibiting the employment of pit brow women (1911) POWE 8/28, The National Archives

Similarly, arguments against the proposed legislation often highlighted the very good health of pit brow women, in comparison to the other ‘clans’ of female industrial workers (see footnote 3). Kate King-May of Manchester University wrote of the ‘healthy, breezy look’ of the women, and notes their strength and good physique thanks to their work (see footnote 4).

The second point made by the government was that the work was unfeminine, and damaged family structures. This links closely to the final point – that there was something about this work which was inherently immoral, and the government felt they were justified in attempting to legislate against it.

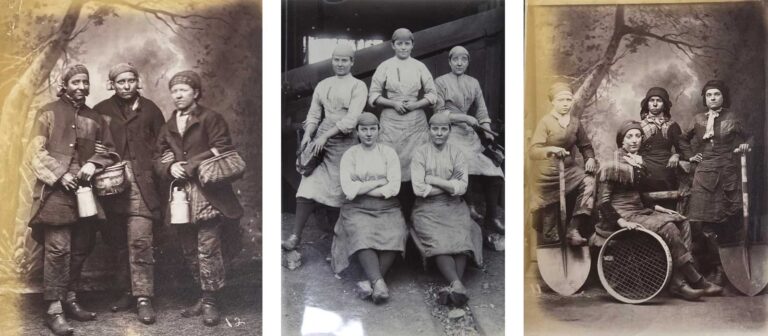

A key reason for this was due to the women’s clothing. They were noted for wearing trousers and clogs whilst working, which were both seen as highly unfeminine.

It has been noted that ‘considerable interest was shown in the “peculiarity of dress” of the Wigan Pit Brow girls. The Select Committee, doing its best to clarify this emotive issue of the girls wearing trousers, had gone to the trouble of obtaining photographs showing pit brow girls at work, and these were used when questioning witnesses about the girls’ tasks and their dress’ (see footnote 5).

Although by far the safest and most practical option for the women, wearing trousers led to considerable backlash from wider society.

The importance of the sources

Taken at face value, the records covered thus far demonstrate some key aspects of life for pit brow women very clearly. However, interrogating documents further can allow some important complexities to come to the fore, revealing even more about these women’s lives.

It is important to note the sheer number of photographs held by The National Archives of pit brow women. As a large number of records tend to be written, it is interesting that there are so many visual sources of these women. If one speculates as to why this may be, it reveals a lot about the contemporary context in which women were campaigning for their employment.

The North–South divide plays a prominent role in modern-day political discussions, and this was also the case over a century ago. It is possible that photographs were used as an important way to inform MPs’ decision making on legislation, particularly when the appearance of the women was so crucial to the debate.

In addition to this, the numerous photographs of individuals go almost exclusively unnamed. By stripping these women of their identities, they are homogenised and othered. These photographs present a distant and distinct group which could be viewed as a threatening and confusing entity by government.

Reasonable inferences made by closely considering the source material reveal not only the complexities of seemingly didactic evidence, but also the importance of questioning the nature of a source.

The National Archives is the official government archive, which means that what is contained within the records was considered important by the government itself. For those like pit brow women, who were opposing the government, and from a background and area which is often very disconnected from Westminster, it means that the sources often do not present them in a positive way.

Kate King-May fiercely challenges the portrayal, from the governmental perspective, of pit brow women as immoral. In her personal experience going ‘undercover’ as a pit brow worker, she described the women as ‘self-respecting, thriving working people’ (see footnote 6).

Pit brow women’s lives can also be illuminated by using records from a variety of sources. Whilst it is useful to discover the official viewpoint, and to see the evidence that governments were sent to challenge parliamentary popular opinion, this is often unrepresentative of the women’s own experience.

A 1947 interview with a former pit brow worker, named only as Mrs P Holden, echoes the description of these women made by King-May. Mrs Holden describes the difficulties she faced during her job, but notes in her old age: ‘I only wish I was a bit younger, I would tackle it again with a good heart’ (see footnote 7).

Piecing stories together

Pit brow women succeeded in maintaining their right to work during every challenge posed by newly proposed legislation. Their employment ended only with the decline of the entire coal-mining industry in the latter half of the 20th century.

Despite the clear visual presentation of pit brow women in the records, their experiences, opinions, and even names, are almost entirely lost. The government perspective in The National Archives contains well-preserved records which, although limited, give valuable insight into the wider contemporary context.

However, if used together with records from elsewhere, which actively centre these women within the narrative, it allows for the piecing together of stories which are too easily lost.

Pit brow women are just one example of those countless others whose lives remain buried within records. By looking closely enough, there is a chance for them to be found.

Footnotes

- Coventry Patmore, The Angel in the House (Macmillan & Co 1863).

- Sarah Edge, ‘The Power to Fix the Gaze: Gender and Class in Victorian Photographs of Pit‐Brow Women’ (1998) 13 Visual Sociology.

- Appeal by the ex-Mayor of Wigan to Secretary of State to vote against amendment prohibiting the employment of pit brow women (1911) POWE 8/28, The National Archives.

- Pamphlet relating the experiences of a pit brow worker (i.e., female surface worker) (1911) POWE 8/26, The National Archives.

- ‘How a Victorian Gentleman Championed the Pit Brow Heroines’ [1979] The Observer Magazine.

- Pamphlet relating the experiences of a pit brow worker (i.e., female surface worker) (1911) POWE 8/26, The National Archives.

- Interview with Mrs P Holden, ‘True Story of a Lancashire Pit Brow Lass’ (1947) <http://nwlh.org.uk/?q=node/196> accessed 10 December 2022. [1] ‘How a Victorian Gentleman Championed the Pit Brow Heroines’ [1979] The Observer Magazine.

How were the occupation of the women recorded in the censuses? Were they hidden in plain sight?

Lovely read Elspeth! Really interesting see you around in HT 🙂

1842 Coal Mines Act forbade employment of children underground below the age of ten, not 18.

Very often the occupation of most women was not recorded. It often didn’t matter what women did, the records will be blank regarding occupation. I had a second cousin once removed who was a surgeon / gynaecologist and her occupation was usually missed out.

Great read. My maternal grandmother was a Pit Brow Lass at a pit in Ashton in Makerfield near Wigan. They were called “Lassies” as a good majority of them were young girls like my grandmother who worked on the Brow from leaving school until she married my grandfather – a miner. My grandmother – Edith Chadwick nee Edwards was born in 1908.

A very quick scan of Ancestry (searching for Holden, pit brow, Adlington, female) reveals some women were shown in 1910 & 1911 census records as working at the pit brow in coal mines – but the only ones I found were teenagers. A more extensive scan with a better understanding of the geography (who worked where etc.?) might be useful. I did extend my scan to include the adjacent census pages to those thrown up by the search. I didn’t find very many pit brow women but perhaps I was looking in the wrong location. More generally, there are usually no occupations reported for wives, in particular the wives of coal miners. However, the occupations of women in the cotton industry (including at least some wives) are reported. As you probably know, some historians are very critical of the way in which women and their occupations were reported in 19C census returns (and probably early 20C census returns as well). The blog and the interview with Holden raise important and fascinating issues.

Really enjoyed this posting. My ancestors come from Wednesbury, a Midlands mining town and I have seen some pictures in Canada(Nanaimo Archives) of pit brow women from Dudley with definitely a family resemblance. Always amazes me to think about the employment conditions of men and women during the 19th century in England and how they survived it. These women picking through coal don’t seem to have gloves on their hands! Years ago I picked up Angela V. John’s book, By the Sweat of their Brow: Women Workers at Victorian Coalmines. I’m encouraged to read it again and next time I’m in your archives I want to pull some of those pictures you refer to.

It is sad that these stories are not part of modern school social history classes. We do those that suffered in labour in past time are not recognised as heroic victims that were abused and denied the most basic of human rights. We stand on their shoulders and owe them debts of gratitude.

In Dearham, Cumberland where I think the pits were open cut, I have seen women described as Coal Pit Bank Pickers (1851 census). It sounds as though they were picking up smaller pieces coal which had fallen from a conveyor or otherwise left behind in the mining. In a particular case (a family member) she was an unmarried mother, so the work provided her with financial independence. It would have been less well paid than the coal hewers, and the men would not have wanted that work?

my observations are the scarves look like burqa’s. The heavy clothing suggests cold conditions were the norm (global warming). Brow means a hill. Hill tops would be first to erode, exposing the coal, so pits would work out from there. Most of the Wigan mines radiated out from Billinge hill. Bank pickers would possibly be working exposed seams such as the banks of a stream, or sea, or cutting of the M6 near Ashton-in-Makerfield. Maybe these girls were mainly young, because few grew old.

I understood that another reason for the banning of women working underground was the fact that it was common the work partly clothed because of the heat.