Legal judgments are important. In the UK they tell us both what the law is and lay bare the details of a case to show us how disputes are resolved fairly.

Find Case Law (FCL) is a service launched in 2022 as a central repository for important judgments and decisions from across England and Wales. At the same time the Open Justice licence (OJL) was established to protect personal data within judgments and to encourage people to re-use judgments in a responsible way.

This blog post is about how the Find Case Law team have supported people to use judgments safely, under the OJL. In the context of public anxiety around emerging technologies and concentration of knowledge, this licence is an important opportunity to build trust that judgments are being handled with care. It delivers on the principles of Open Justice – that ‘Justice must not only be done, but must also be seen to be done’. Greater access to judgments means greater potential for researchers to discover new insights or for organisations to deliver innovative and important services.

The OJL is definitive. It applies to all judgments. It clearly states that you can re-use judgments if you follow its terms, so users can be confident in what they can and can’t do. It’s free and you don’t need to apply to follow its default terms.

One of the terms is that you can’t do computational analysis on judgments. If you want to programmatically identify, extract or enrich information across judgments in bulk, you will need to apply to do computational analysis. This extra step is deliberate friction, designed to prompt people looking to re-use judgments as data – ‘re-users’ – to consider the risks of using judgments and to develop safe practices.

Building trust in responsible re-use

A licence is a symbol of responsibility for everyone. Licence holders want to demonstrate to the public that their service or research is reliable. The question is: what makes us collectively trust a licence? Here are three suggestions:

- Establishing safe practices

- Consistency and fairness

- Clarity and transparency

I’ll explain what I mean by each of these.

Establishing safe practices

Each judgment is hand-crafted by each judge to respond to the case before them, essential for justice being delivered. As more judgments are published, there is increasing value in understanding them all together. However, judgments have not been consistently structured in the same way as say, legislation. It’s not easy to aggregate them.

Large natural language models are an exciting development. They offer the potential to automatically derive structure and categories where they had not been assigned before, to hopefully generate new insight. But the methods used to do this can vary and produce different outcomes, with inevitable contradictions, hallucinations, and the potential to mislead.

Safe practices are needed. In 2023 the Ministry of Justice established nine principles for use of data. These principles provide us with a consistent framework for understanding responsible practice and appropriate risk for computational analysis. In response, we revised the application process to make it easier for applicants to tell us what computational analysis they wanted to do and how.

We moved away from just asking open text questions based on the five safes framework. The application is now in two halves, with a mix of open text and multi-select questions. The first half starts with basic questions designed using GOV.UK form elements. For more context-specific questions we used emerging design patterns from grant-funding applications as inspiration, to help consistently identify organisations and the purpose and benefit of their proposed analysis.

Through usability testing we observed how applicants wanted space to publicly declare their ambitions in their own words. This tied in well with our aspirations to be more transparent about the types of computational analysis that have been approved. Thus the public statement was born.

The second half of the application is more bespoke to the nine principles. In prototypes we tried a one-page-per-principle approach. This made the application very lengthy and restricted the applicant’s ability to relate to the principles. We replaced this with a quick series of Yes/No questions about the applicant’s methodology, warming them up to an essay question asking how applicants will meet the nine principles in practice, identifying any risks and how they will mitigate them. To encourage candidness we do not have plans to publish these answers.

Once the application is submitted it is reviewed by our licensing department . All decisions made on applications are reviewed by our governance bodies to make sure we are supporting safe re-use.

Breaking the application process down into focused sections has made it clearer for applicants to complete. It has increased confidence among applicants that everyone goes through the same process and has to provide the same level of detail.

Consistency and fairness

Find Case Law publishes judgments on the public web. This means everyone has free and equal access to the same judgments under the same licence. This is consistent, but we have gone one step further to make sure more people can reliably identify the judgments they need in the formats they need.

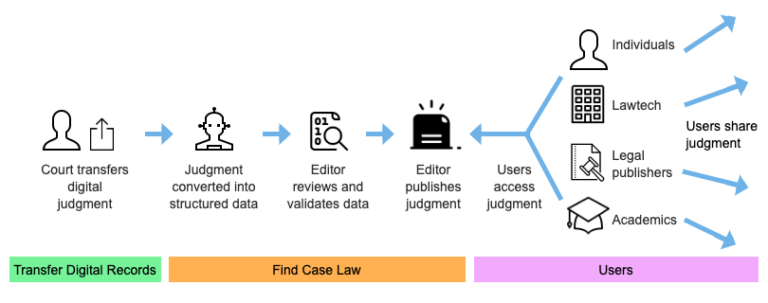

We publish every judgment as HTML, PDF and XML (a machine-readable format). We automatically mark them up against international data standard LegalDocML. We have done this by training a parser across thousands of judgments. The parser identifies information within the document, the most important of which is then reviewed and validated by our publishing editors, so people can be confident that the information is reliable.

After due diligence checks the judgment is published for the first time to both the FCL website and an atom feed that supports programmatic access to judgments. This means that everyone benefits by being able to quickly find the latest judgments. This consistent experience supports analysis across services and jurisdictions.

To ensure fairness, everyone who accesses judgments on FCL does so under the Open Justice Licence. We want to make sure anyone can apply to do computational analysis, so we’ve focused on being clear and transparent about the process and our decision-making.

Clarity and transparency

To increase confidence and build trust in the Open Justice Licence (OJL), we clearly define what is being licenced and all the processes involved. Our draft Open Justice Logo is designed to signify judgments are available for being used responsibly.

In 2022, for the first time, the OJL authoritatively defined terms of use. Only one sticking point remained: ‘What does ‘computational analysis’ mean?’. We’ve added examples such as computers programmatically reading, identifying, extracting and enriching judgments in bulk, but this is not an exhaustive list. ‘Computational Analysis’ can take into account emerging techniques as they are adopted. If in doubt, you can email our Licencing department, who are there to talk with potential applicants.

We have added pages about the application process to support potential applicants to prepare. We have also iterated on the questions, adding fictional example answers to bespoke questions such as the public statement, to help crack the blank paper problem.

Asking applicants for things like a public statement reflect our aspirations to be more transparent about the activities that have been licensed, and to publish these responses.

Data users are users too

We’re not done. We’re responsive to emerging users, needs and technologies. We closely monitor the service to see how we can improve it for all our users, including those who want to re-use judgments. If you want to share your experience of working under the Open Justice Licence, please contact us at caselaw@nationalarchives.gov.uk or volunteer to take part in research by completing this short survey.

You can read more about the licence and application process on the Find Case Law website.

Thanks to our Senior Interaction Designer, Terry Price, for creating the images for this blog post.

Of course it doesn’t apply to Scotland which has thankfully has a different legal system.