Today has seen the release of Prime Minister’s Office and Cabinet files from 1989 and 1990. Some of the most significant events of the period are represented, such as the reunification of Germany, the introduction of the Poll Tax (and ensuing disturbances in Trafalgar Square) and the end of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership.

As ever we are provided with a greater understanding of the concerns of the Prime Minister and the Government, how those concerns stretched into new areas, and the breadth of perspectives a release of files of this kind can provide.

Today, however, we take a closer look at some of lesser known events covered by the files: diplomats struggling on as Iraqi forces besieged Kuwait City; letters of condolence prepared pre-emptively (and prematurely) by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) for the death of Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping; and the interest the Home Office – and the Prime Minister – took in curtailing acid house parties.

Embassies under siege

In June 1985, the new ambassador to Kuwait, Peter Moon, complained about the state of the British embassy in Kuwait City, describing it as ‘shabby’ and ‘bursting-at-the-seams’ (FCO 8/5838). Luckily, he didn’t have to spend several months in the building, besieged by Iraqi troops. His successor’s successor, Michael Weston, did. You can read part of his story in newly released PREM 19/3080.

Map to show the limits of Kuwait and adjacent country, 1954 (MFQ 1/1229)

On 2 August 1990, Iraqi troops crossed the Kuwaiti border and captured the capital. On 9 August, Saddam Hussein ordered all diplomatic missions to close and move to Baghdad by 24 August. When they failed to comply, water and electricity were cut off, and a long siege began.

On 1 September, The Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Douglas Hurd, managed to talk to Weston by radio. Weston reported that they still had enough water and food to hold out, and that, in fact, ‘the quality of the food had improved since the departure of the cook.’

On 4 September, he was able to transmit a longer report on his situation as well as on that of other diplomatic missions. It had been suggested that they should all ‘congregate’ somewhere in town, either at one of the embassies or at a hotel. Weston thought it was highly ‘impracticable’. By that time, hotels in Kuwait City were used as ‘holding centres for foreign nationals’, and diplomats would no longer be able to communicate. Joining forces with colleagues wasn’t that easy either. The East German ambassador had tried to reach his West Germany counterpart’s residence, but was ‘picked up’ by the Iraqis and taken to Baghdad.

For that very reason, the Italian ambassador (‘a splendidly robust fellow’) was living in his chancery ‘in great discomfort’ as it would be too risky to ‘travel daily to and from his air-conditioned residence, 12 kilometres away’. The French, Weston said, were suffering as well but could probably hold out longer than they claimed: given the location of the French Chancery, in which the Chargé was besieged with three colleagues, they could ‘send out ‘pigeons’ and bring in supplies in small quantities.’

Weston didn’t know much about the situation at the Greek Embassy due to the Greek ambassador’s apparent lack of linguistic abilities, but he learnt from the Italians that he was ‘most uncomfortable.’ Morale, he said, was wavering, and he detected a bit of resentment towards Britain, held responsible for the whole situation by most of his colleagues except the Frenchman and the Italian. He thought some of them may be putting on a brave face but sorely tempted to just give up, and wrote:

‘The weak links are the Greek, the Spaniard, the Dane and the Belgian. The first three are basically lonely and have nothing to do, though the Dane keeps himself amused by sending messages on behalf of the others. I am fond of the Belgian, but he is old and tired, and very nervous.’

The typical stiff upper lip, for which Michael Weston was later praised by Margaret Thatcher and Members of Parliament, prevailed on the British side. The fuel situation was a bit worrying, but they were saving water by using the swimming pool to wash (even if its water was ‘stagnant’). In September, temperatures in Kuwait City are high in the 90s, and the ambassador confessed to suffering from ‘the heat and the insects and the lack of any fresh food,’ but he thought appearances had to be kept. After all, ‘the more ragged and smelly he and his colleagues were when they eventually left, the greater the propaganda victory for Iraq.’

Throughout the siege, the ambassador and his consul, Larry Banks, helped with the evacuation of several hundred British nationals to Baghdad, and managed to keep in touch with the remaining members of the British community and provide them with as much support as possible. The British embassy was one of the few diplomatic missions which remained open throughout the crisis. We do hope Weston and Banks got to sample the ‘pre-invasion vintage (both red and white)’ they bottled during the war, as well as the ‘special beer’ they were brewing ‘to commemorate the relief of the siege, whenever that may be’!

Letters of condolence

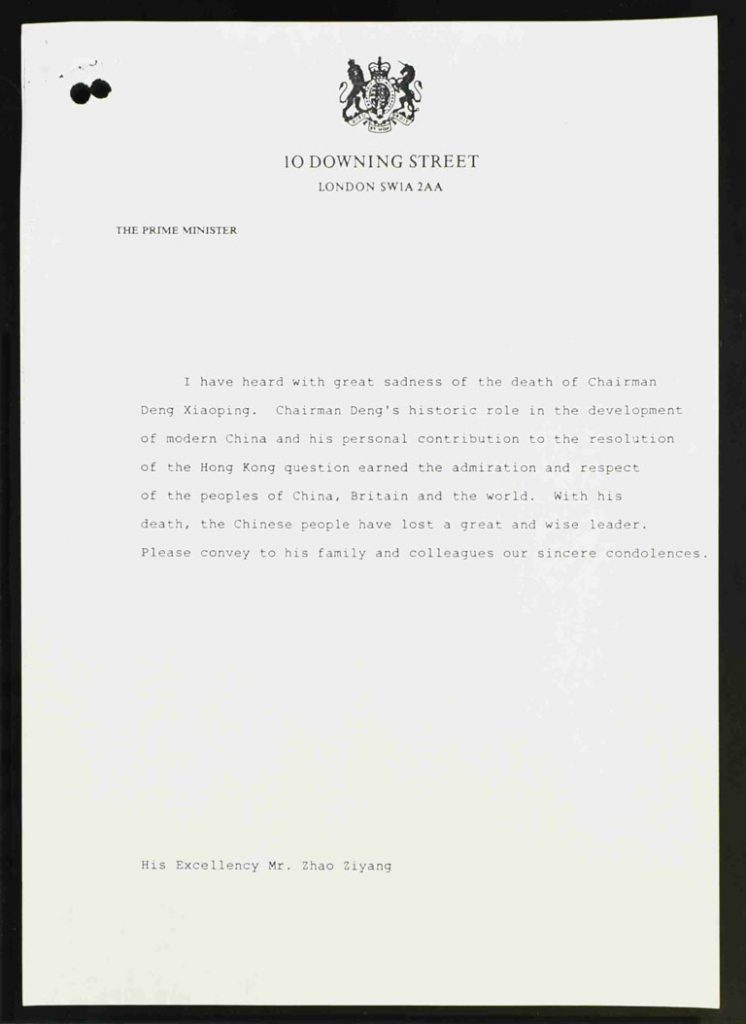

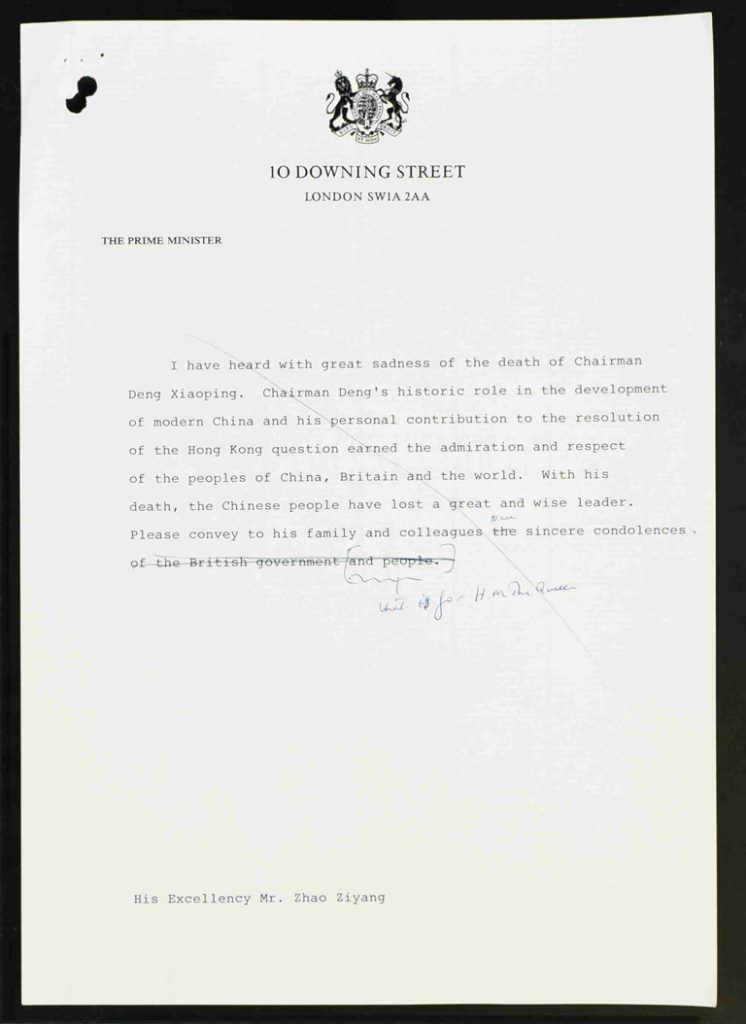

Browsing through PREM 19/2597, a file on the internal situation in 1980s China, we were somewhat surprised to come across a letter on headed 10 Downing Street paper offering condolences on the death of the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping. Deng was one of the most influential Chinese leaders of the 20th century and we were sure that he had not died until well into the 1990s. Following some frantic checking we confirmed that Deng had not passed away until 1997, at which point we returned to the file to try and work out what on earth was going on.

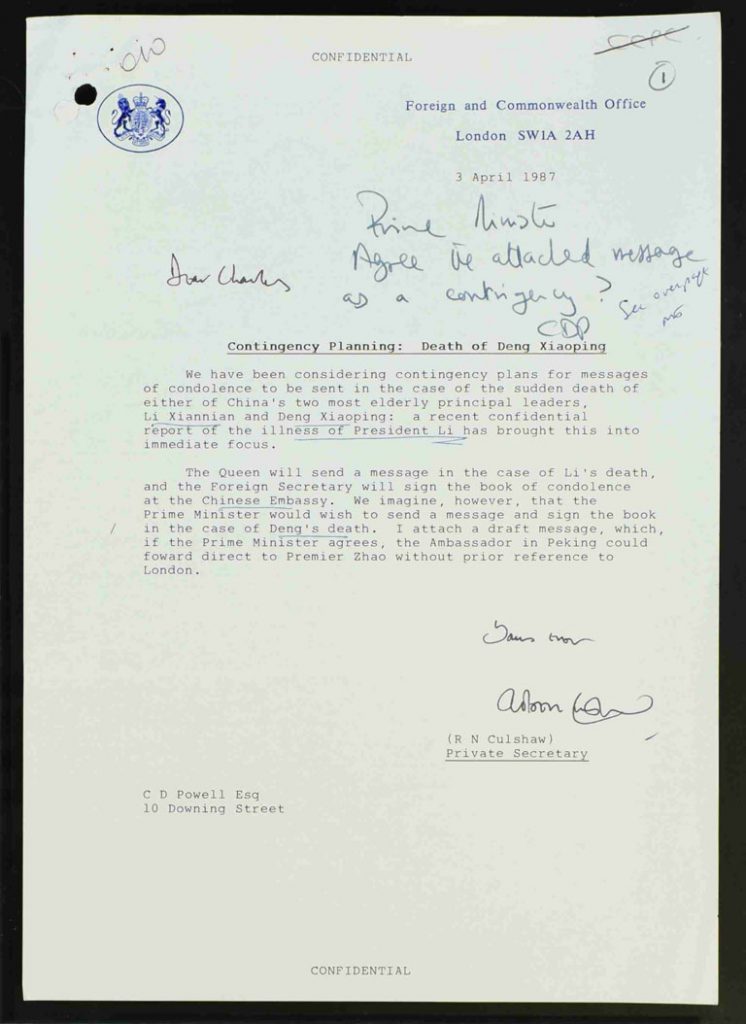

A letter from Robert Culshaw at the FCO to Charles Powell, the Prime Minister’s Private Secretary in April 1987, sheds a little more light on the situation. The FCO, concerned following the recent illness of President Li Xiannian, had been preparing contingency plans ‘in the case of the sudden death of either of China’s two most elderly principal leaders’.

- FCO contingency plan for deaths of Chinese leaders – Deng Xiaoping (PREM 19/2597)

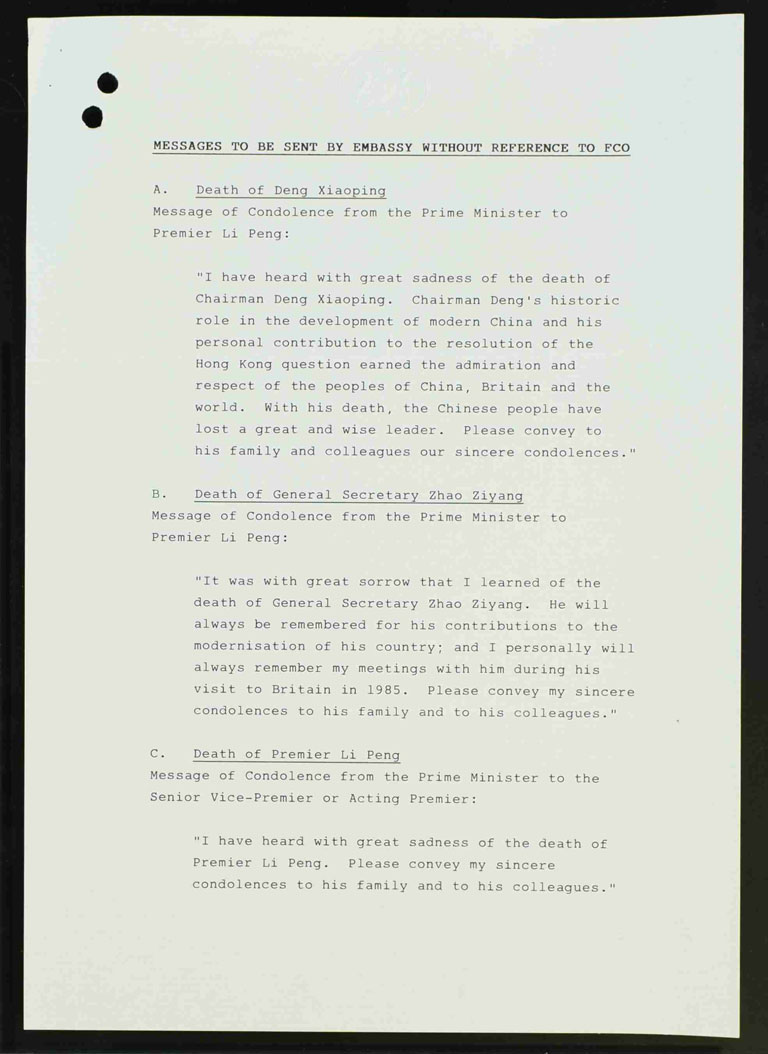

The letters drawn up were carefully reviewed by Margaret Thatcher and it was agreed that they could be sent out by the Embassy in Beijing without reference to London. Just over a year later the FCO decided that they need to update their contingency planning in view of changes in the Chinese leadership. As such they sent Thatcher a rather remarkable document with three draft messages of condolence for the major Chinese leaders, Deng Xiaoping, Zhao Ziyang and Li Peng. [PDF Image no 194]

Draft messages of condolence for Chinese leaders Deng Xiaoping, Zhao Ziyang and Li Peng (PREM 19/2597)

As it happened this level of readiness proved unnecessary. Deng lived on until 1997, Zhao until 2005; Li remains alive to this day.

The acid house ‘fashion’

Having emerged in Chicago in the mid-1980s the electronic music sub-genre of acid house had gained in popularity in the UK and by 1989 had firmly broken into the mainstream. The scene relied upon parties in large spaces without restrictive licensing laws, such as warehouses or open fields, but at the same time as devotees were declaring a Second Summer of Love, critical and exaggerated media depictions of drug-fuelled and hyper-sexualised raves organised by drug barons were leading a backlash.

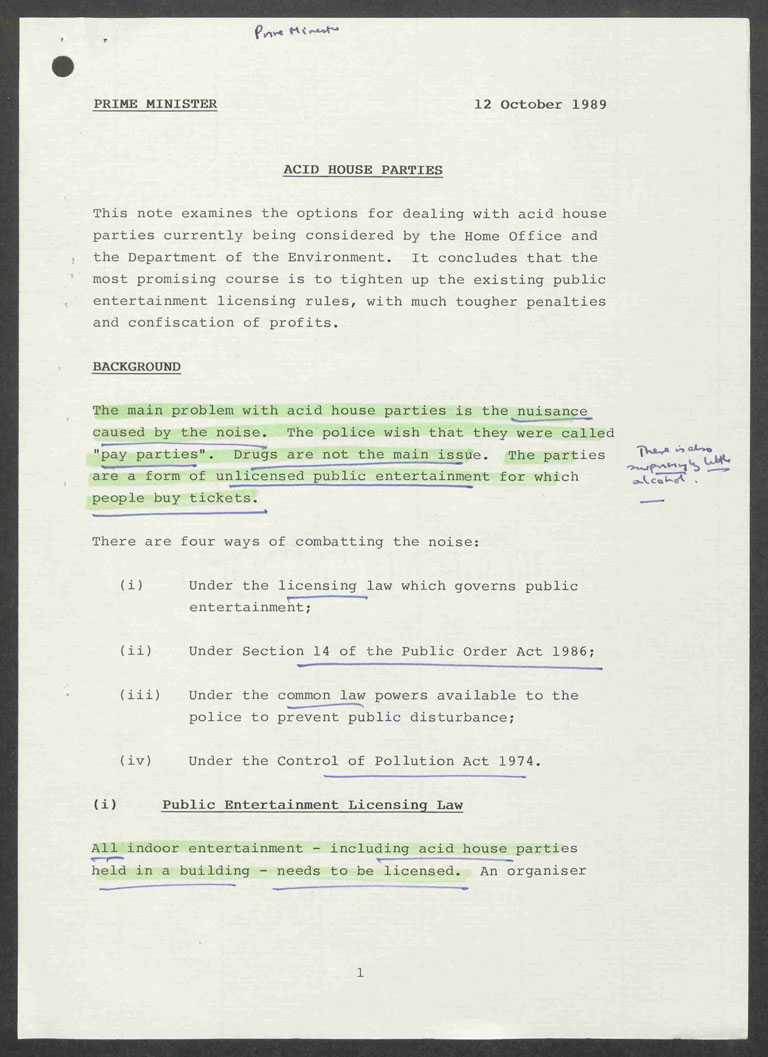

To that background a file released today (PREM 19/2724) shows us that the government – and Margaret Thatcher herself – took great interest in the phenomenon of acid house parties and took steps to curtail them, primarily on the grounds of excessive noise.

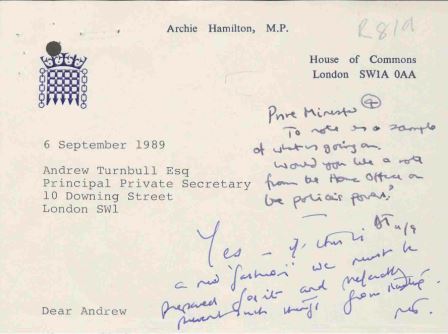

Archie Hamilton MP provided a letter in which his uncle – Gerald Coke – detailed the effects of an acid house party in the village of Bentley, Hampshire in August 1989. Coke explained how ‘virtually everyone in the village rang the police at some stage’ to complain about the noise of the party, which ran throughout the night.

Coke listed legislation he as a former magistrate felt could be used to restrict any future parties, but struck a generally pessimistic tone, noting disappointment in the police response. He also warned that locals may take matters into their own hands, warning ‘Such action would, of course, be quite fruitless and could well lead to bloodshed or serious damage to property’.

The note was provided to the Prime Minister by an adviser who asked whether she would like a note from the Home Office on current police powers for acid house parties. She replied, ‘Yes – if this is a new “fashion” we must be prepared for it and preferably prevent such things from lasting’.

The Home Office soon responded pointing to powers under the Public Order Act which restricted open air parties and indicated the possibility of using breach of the peace laws, especially if people were likely to take matters into their own hands after making complaints to the police. The Home Office also suggested that there could be a change to the Public Order Act to require party organisers to give notice to the police.

A note from Carolyn Sinclair of the Number 10 Policy Unit detailed some of the problems police had been facing – namely that making noise alone was not a criminal offence – and also provided some further suggestions, such as ‘hitting the profits made by the organisers’, adding, ‘this should discourage the craze’. She noted that the Home Office were looking at strengthening licensing laws but underlined the fact that – contrary to some of the media depictions of the parties – noise was the main problem to be dealt with, stating: ‘Drugs are not the main issue’.

Carolyn Sinclair’s note on acid house parties to the Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher: ‘Drugs are not the main issue’ (PREM 19/2724)

The rest of the file includes other cabinet ministers voicing their opinions on the matter as the Government moved towards strengthening licensing laws and increasing penalties for organisers. By March 1990 these changes were being debated in Parliament and subsequent alterations to the law – alongside a changing electronic music culture – saw fewer outdoor parties and raves and the development of a club culture that existed in spaces that could generally be policed, licensed and monitored more easily. Today, as a result of this file release, we learn how Margaret Thatcher and her Government contributed to that change.

I think that to understand the events you need to look at the background in the country and these files that have been released (not yet on Discovery) are a small part of Government and from a certain viewpoint (i.e. Margaret Thatcher). and you need files from other Government departments to see ‘the bigger picture’. I note the lack of any mention of the economy/economic issues. Incidentally as regards Kuwait, ‘East Germany’ and ‘West Germany’ did not exist but were the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany and the UK had long had an issue with allowing/agreeing to unification of the two parts of Germany.

[…] Direct to National Archives Blog Post About What’s Found in Files […]