The events of 1984 – including the murder of WPC Yvonne Fletcher outside the Libyan Embassy and the extraordinary IRA plot to assassinate the Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher by blowing up the Grand Hotel in Brighton – combined to make it one of the most dramatic years in contemporary British history. It is perhaps the miners’ strike of that year, though, that has had the most lasting impact on British society, with the dispute which lasted almost an entire year from March 1984 to March 1985 shaping the political landscape, media representations, and local communities in the decades since.

A police line in South Yorkshire during the 1984-85 miners' strike. By http://underclassrising.net/ (Flickr: Great Miners' Strike of 1984/85.) CC-BY-SA-2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The files from 1984 released today at The National Archives show how the Government attempted to deal with these events. The warnings received by the UK Government of potential violence ahead of the demonstrations outside the Libyan Embassy in London (PREM 19/1300), the possibility of slowing British-Irish negotiations following the bomb in Brighton (PREM 19/1288), and the seven hefty files on the damaged industrial relations with the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) (PREM 19/1329-1335) show the swirl of activity and the sheer variety of hefty issues which passed over the Prime Minister’s desk. [ref]1. As ever, of the Prime Minister’s Office files (PREM) and Cabinet papers (CAB) released, a selection have been digitised and are available to download from the website, free of charge for a month.[/ref]

But what can we learn about the miners’ strike, a subject about which so many texts have been written, after so many of its recriminations were played out in public? The firmness of Thatcher’s resolve to be victorious would not surprise many, and nor would the breakdown of negotiations between the NUM and the National Coal Board (NCB). The lessons we do learn from this file release may not play out perfectly in a succinct headline, but rather in a broader study of a dispute years in the making, with long-standing repercussions.

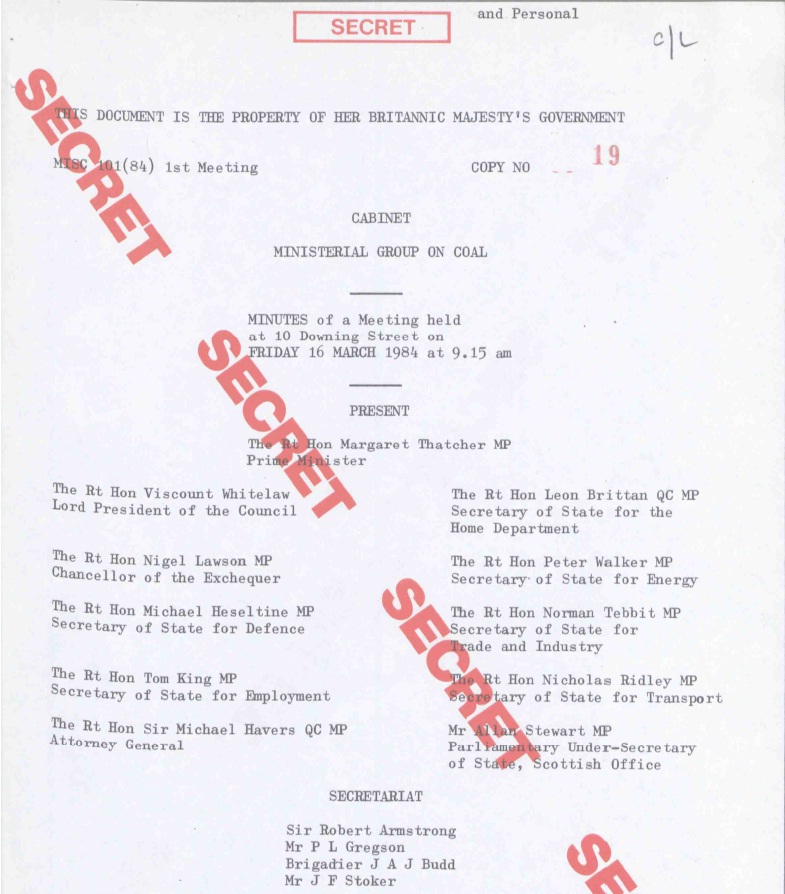

For years the Government had been planning for a miners’ strike, by replenishing coal stocks to reinforce power station endurance. The possibility of power cuts and a repeat of the political disaster of the three day week during Edward Heath’s premiership ten years previous was unimaginable. Indeed, in the months leading up to the strike – in the second half of 1983 – we can see from the files that preparations for industrial action were ongoing and were limited to an increasingly small group of ministers. At a particularly revealing meeting in September 1983, only the Prime Minister, Chancellor Nigel Lawson, and Secretaries of State for Energy and Transport – Peter Walker and Tom King, respectively – were present (PREM 19/1329). When industrial action began in March of the following year, a similarly small group of ministers met to discuss the government’s reaction. This theme continued with the establishment of MISC 101, the Ministerial Group on Coal, the papers of which can be found in CAB 130/1268.

The smaller Ministerial Group on Coal met for the first time on March 16th 1984 (CAB 130/1268)

The interesting element of this centralisation of ministerial decision-making is the cautiousness surrounding the sharing of information even within the Cabinet, and indeed it even echoes ministerial activity during the Falklands War. The over-riding desire was to, as PL Gregson of the Cabinet Office stated, avoid ‘misunderstandings’. It is this question of misunderstandings – perceived or otherwise – which drove another element of the Government’s activity during the strike, the attempt to influence public opinion at the same time as keeping at least a veneer of separation from the NCB and their confrontation with the miners.

Throughout the dispute the government – usually through the prominent Peter Walker – placed pressure on the NCB and its chairman Ian MacGregor to improve its communications, as public opinion largely remained on the side of the striking miners. It was vital for the government that it was clear the NCB was making the decisions but equally important that the aim of closing uneconomic mines and establishing an efficient mining industry was expressed effectively.

Importantly, though, it is clear from such a file release that a more nuanced view of the dispute can be established. For all the firm rhetoric, there were pressure points during the dispute – particularly when other unions threatened to strike – that the government was less than certain that the coal stocks so carefully cultivated, would last beyond the winter of 1984/85.

In July 1984 as a dockers strike threatened the import of coal from abroad the government looked into the procedures for declaring a state of emergency (PREM 19/1331) and in October, when the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers (NACODS) threatened their own dispute, the option of a three day week was discussed (PREM 19/1335). As those other unions compromised, though, the NUM was left isolated and the NCB and the government was able to strengthen its position.

As ever, it is the new insight into government discussions, decision-making, and even organisation which make these file releases so interesting.

Whilst these files are interesting it is only part of the story and one hopes that the Treasury would release their files to complete the picture, given the financial interest they would have had. I don’t think we should be surprised that Government had plans to counter any coal strike, or indeed any public service dispute, or that only a few ministers knew about what was going on, that is what Government is there for. The fact that the Prime Minister had lots of issues to deal with should not come as a surprise.

David,

The point I was getting across is that by centralising decision-making to a group of ministers even smaller than the Cabinet the government was dealing with the strike in a manner that was unusual. Cabinet level decision-making is what one might expect, not an even smaller group to avoid ‘misunderstandings’.

It is true it is not a surprise that there were plans to counter a strike. Over the previous years the stockpiling of coal to ensure power station endurance was secret, but released in recent file disclosures, which you are free to view in the reading rooms. As ever, though, we learn a lot from these releases – about how government operates at times of crisis and what exactly a Prime Minister views on such occasions.

Thanks for reading.

Simon

I could be wrong, but my recollection of the period is that it was common knowledge that HMG had had a large amount coal etc stockpiled in the event of a Miners Strike.

I believe that it was general knowledge, but it would seem that the NUM did not appreciate that the high volume of coal at the power stations had tilted the field against them, and a strike could be left to run until it hurt them. If only Trade Union records were made public after a similar period.