This is the second of a two-part blog exploring the records at The National Archives that can help us understand the impact of the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic.

The impact of the influenza on persons from the front can be discovered using the record series MH 106, a record series at The National Archives that is a representative sample of the service personnel medical records that were created during the First World War.

About half of the medical sheets from the series have been catalogued to item-level (meaning they are searchable by name and/or regimental number) by a project funded by the Wellcome Trust. Three volunteers are currently working on enhancing the catalogue descriptions of the second half of these records, with help from The Friends of the National Archives, who have lent financial support to turn it into volunteer-led project.

’Flu on the Front

The Western Front bore the brunt of the early outbreaks, with reports in April 1918 that influenza was prevalent at several military bases. One of the earliest reports of the pandemic can be found in Cabinet Office minutes from 17 May 1918, where it was reported that the docking of the ship HMS Weymouth was postponed due to an outbreak of 211 cases of influenza on board[ref]Cabinet Office Minutes, 17 May 1918, CAB 23/6/35.[/ref].

The war diaries for the Director General of Medical Services from June 1918 give us further insight into the first wave of the pandemic. On the 22nd it was reported that:

‘A widespread epidemic of highly infectious fever of short duration has been raging throughout the British Armies as well as on the Lines of Communication and at the bases and still continues. The incident has been greatest in the First and Second Armies and amongst other troops in the Northern Part of the British zone. French and Belgians both civil and military are affected, and in all probability the German troops also, as captured documents refer to an epidemic of fever which is keeping units out of the line.’

War Diaries, Director General Medical Services, 22 June 1918, WO 95/47/5, p. 128

The first wave, however, was relatively mild and there seemed to be no real cause for concern; men were fit to return to duty from 7 days to 10 days. The war diaries also show what attempts were made to curb the spread. It was relayed that:

‘Steps are being taken to limit as far as possible the spread of the epidemic, by distributing troops as widely as possible in camps, billets etc. keeping drafts in reinforcement camps in separate lines for four days, airing blankets and kits, and arranging for troops to sleep in the open air if possible.’

War Diaries, Director General Medical Services, 22 June 1918, WO 95/47/5, p. 138

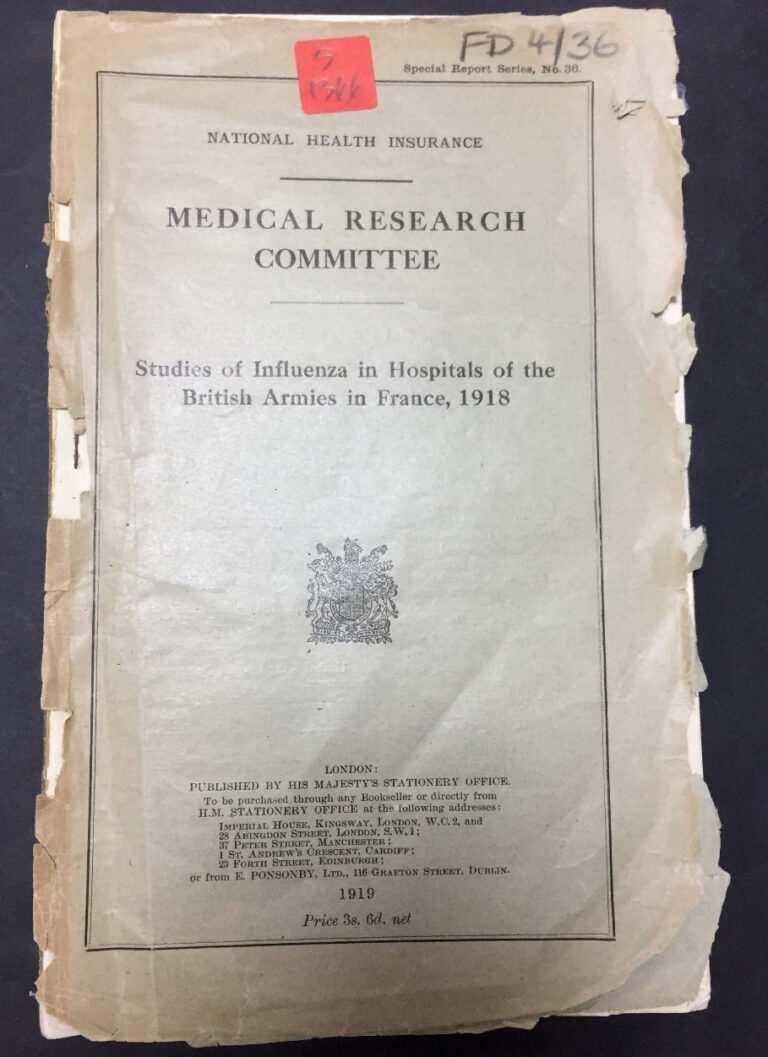

The Army went on to carry out a lot of the earliest work on the outbreak under the auspices of the Army Pathology Advisory Committee, working very closely with the Medical Research Committee over the course of the pandemic[ref]Army Pathology Advisory Committee to the War Office: MRC representation (1918-1929), FD 1/4261.[/ref].

Sadly, the relatively mild nature of the outbreak was short-lived and the autumn saw a more virulent second wave. In most cases of the influenza it is commonly the most vulnerable people – like the very young, sick, or old – tending to fall ill. However, the virus responsible for the 1918-1919 outbreak was unique, in that the mortality of healthy young adults saw a distinctive rise – thereby impacting many of those fighting on the front lines.

MH 106: Service personnel afflicted by the ’flu

William Robert Bruce-Clarke (MH 106/2202/245)

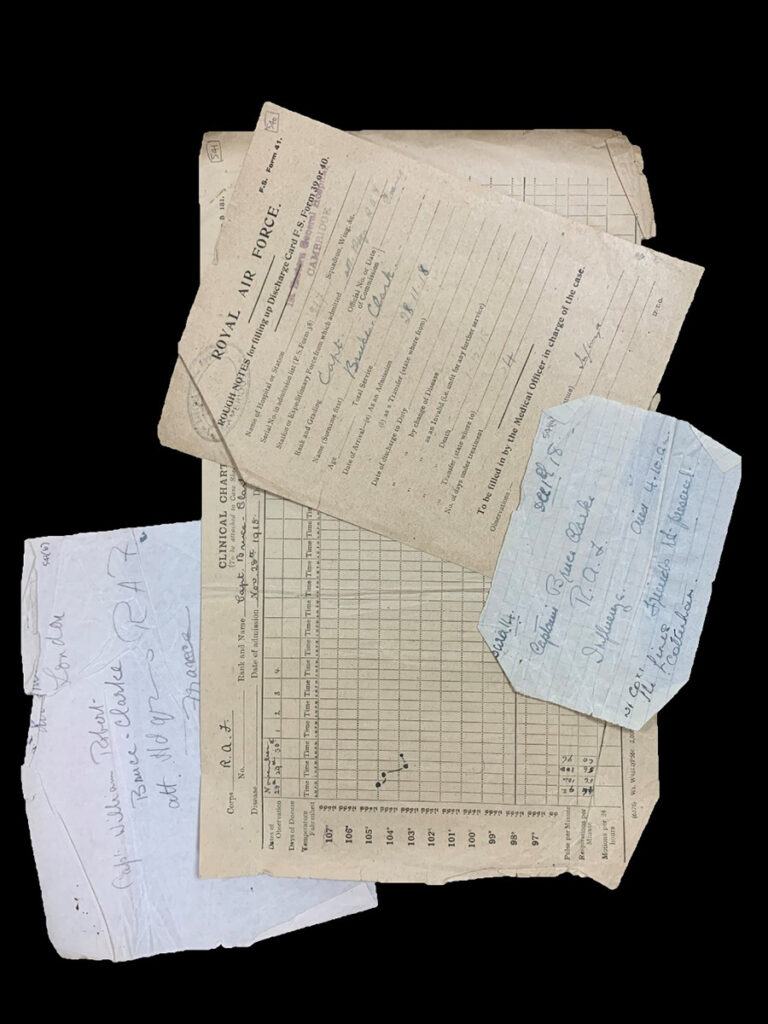

William Bruce-Clarke, born 24 June 1886, was educated at Harrow School and went on to study engineering at Trinity College, Cambridge, graduating in 1909. His service record relays that he had ‘conversational knowledge of French and German’[ref]Department of the Master-General of Personnel: Officers’ Service Records. Bruce-Clarke, William Robert, AIR 76/90/122.[/ref].

William fought in France during the War and managed to make it home in November 1918 on 48 hours leave to visit his wife Ethel who had come down with the ’flu[ref]H Gault, ‘WWI and the flu pandemic: life, death and memory’”, The Historian, (Autumn 2015), pp. 42-43.[/ref]. Ethel recovered but tragically William caught it and – after four days of treatment – died at the 1st Eastern General Hospital in Cambridge on 1 December 1918, aged 33.

His records in MH 106 include a discharge form from the army, a clinical chart and two notes.

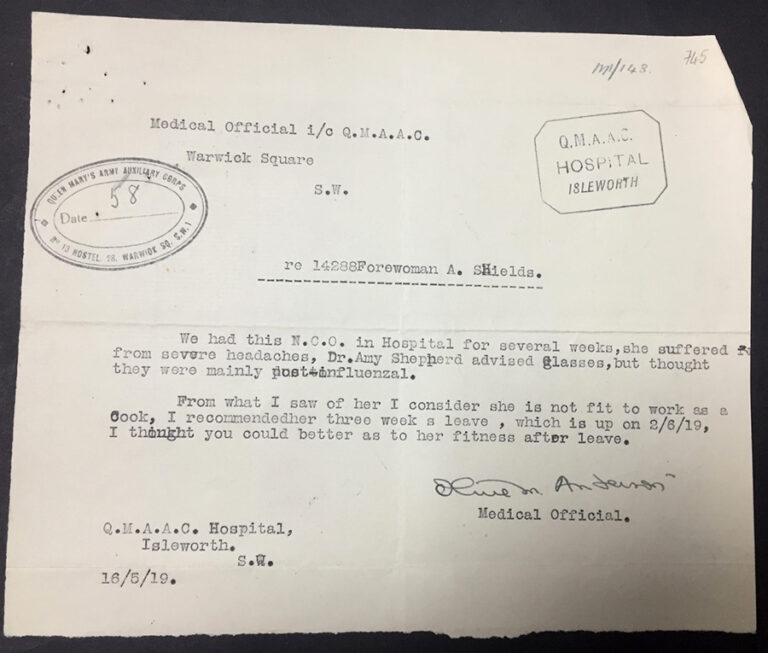

Alice Shields (MH 106/2208/284)

Another story we can draw out is that of Alice Shields, a cook in the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps. Alice came down with the influenza in June 1918 at the age of 34. The records tell us that she wasn’t discharged until over one year later in July 1919, after five periods of treatment for debility. We have her diet chart, which interestingly shows that Bovril was a mainstay of her treatment and also indicates that while most people recovered or died from the ’flu in a short period of time, some cases had lasting effects, with symptoms lasting many months or even years.

Her records include two medical case sheets, five diet sheets, five clinical charts, one morning sick report, one medical board slip and four notes.

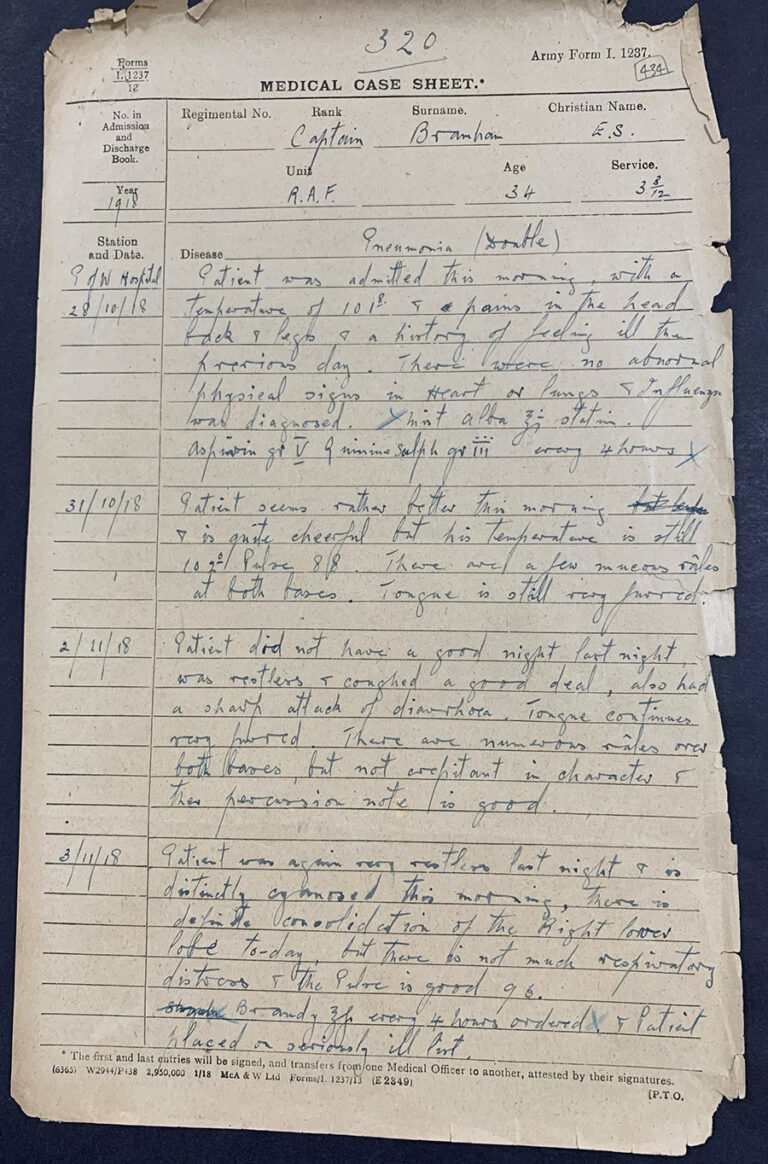

Ernest Stewart Branham (MH 106 2202/200)

Born on 14 June 1884, Ernest began working for the Great Western Railway (GWR) in the Goods department in Gloucester from the age of 15[ref]GWR Staff Records, Register of Clerks. Vol 8, 1835-1910, RAIL 264/9.[/ref]. In July 1915 – now aged 31 – he joined the Royal Flying Corps, where he rose through the ranks[ref]Department of the Master-General of Personnel: Officers’ Service Records. Bramham, Ernest Stewart, AIR 76/52/91.[/ref]. In September 1917 he married a French woman named Yvonne[ref]Gloucester Journal, 25 January 1919. British Newspaper Archive.[/ref]. However, the medical records show he was invalided home from France with debility that same month. After another period in France (now a Captain in the RAF) he returned to England in October 1918, where he caught the ’flu.

Captain Bramham was admitted to the Prince of Wales Hospital for Officers on 28 October 1918 with influenza and double pneumonia. Three days later it was noted that he ‘seems rather better this morning & is quite cheerful’, despite a high-temperature. On 2 November, however, Captain Bramham had a restless night and ‘coughed a good deal’. The next day he was prescribed brandy every four hours and placed on the seriously ill list. On 4 November a doctor stated he was ‘deeply cyanosed’, which meant his skin had turned blue. The next day he was delirious and he sadly passed away on 7 November, aged just 34.

His obituary in the Gloucester Journal noted that ‘Besides his friends and colleagues in the Electrical Engineer Department and in the GWR (London) Athletic Association, a large circle of friends, inside and outside the railway, deplore his loss’.

His records in MH 106 include four medical case sheets, a clinical chart and a medical board note.

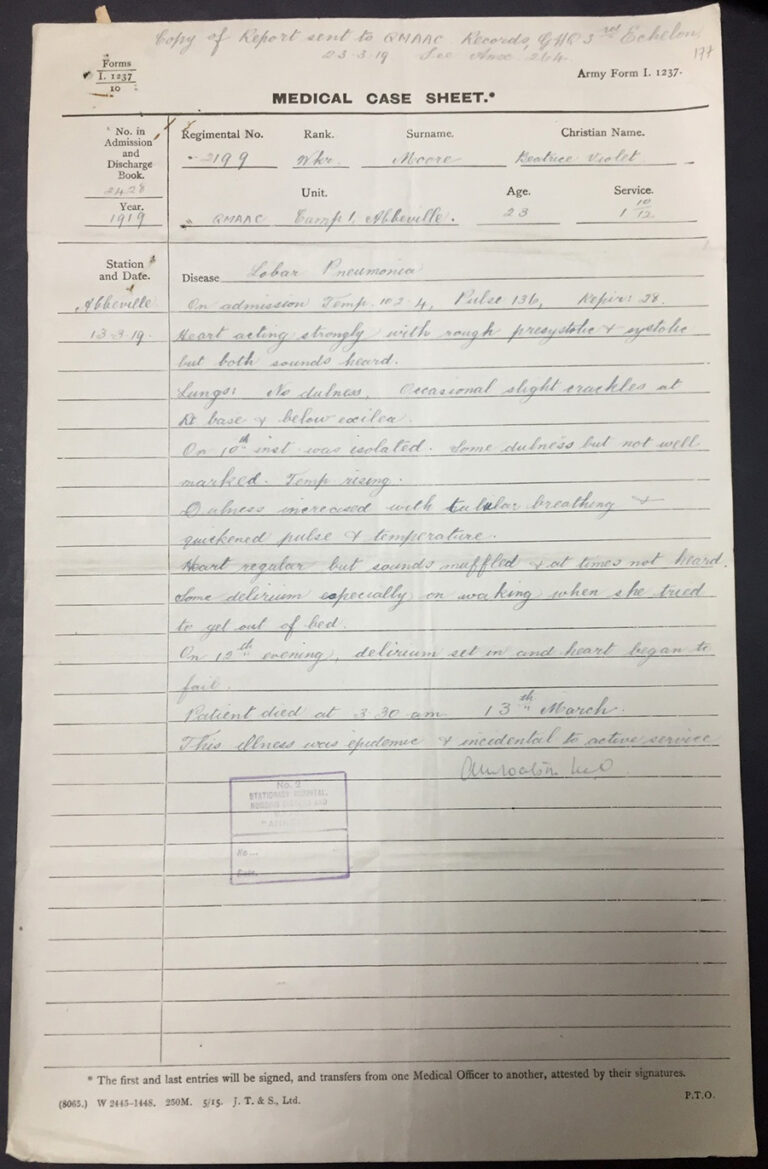

Beatrice Violet Moore (MH 106/2208/66)

The end of the war provided no relief from the ravages of the ’flu. Demobilisation from service following the conclusion of the war took a number of months, and many soldiers and auxiliary workers continued to serve into 1919. For example, the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAAC) were kept on in France after the war to help with the clean-up operation, as well as to tend to the newly created cemeteries.

When the final outbreak of influenza happened in the spring of 1919 many soldiers and workers were still abroad. Tragically it was during this outbreak that Beatrice Violet Moore, a worker in the QMAAC, caught the ’flu. Moore’s medical records sadly record her demise – as the 12th evening closed in she became delirious and her heart began to fail. She died on 13 March 1919, aged just 23. A note at the bottom of the record states, ‘This illness was epidemic & incidental to active service’.

Her records include a laboratory report and two medical case sheets.

How to search for records

MH 106 records are an excellent resource for military, medical, and family historians. Search the series for medical sheets here by name, regimental number, or type of affliction.

The series is still undergoing cataloguing enhancement, so please bear in mind that some medical sheets are catalogued by alphabetical name-range only. You can browse by hospital or regiment here.

These records are only a small representative sample of the medical records created during WW1. The majority of records were destroyed in the 1970s.

Digital images of the representative admission and discharge registers can be searched online through our partner FindMyPast, in the collection British Armed Forces, First World War soldiers’ medical records.

Astonishing that most of the record were destroyed in the 1970s, why did the Public Record Office not intervene?.

The first world war influenza is similar to today’s Corona viruse but now we hopefully have a better thing in the vaccine and vaccination.

Child mortality in the 1900s was at a high.