This is the first of a two-part blog exploring the records at The National Archives that can help us understand the impact of the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic.

Just over a century ago, an unusually deadly influenza pandemic broke out, killing an estimated 50 million people worldwide. Globally, it claimed around five times more lives than the fighting in the First World War. In Britain, the first wave of the ’flu appeared in the spring of 1918, followed by a more virulent second wave in the autumn, and a third wave in the spring of 1919. Many of those afflicted died as a result of secondary bacterial pneumonia infections. In total, it is estimated that the outbreak claimed around a quarter of a million lives in Britain alone, affecting every section of society.

Public Health response

Britain’s public health system had undergone vast improvement in the 19th century yet the country was tragically unprepared for the pandemic, particularly as the influenza itself was not a notifiable disease. Infectious diseases, like cholera and smallpox, were classed as ‘notifiable diseases’ – meaning that medical practitioners and local authorities were supposed to notify the government in the event of an outbreak[ref]List of notifiable diseases by date: House of Commons debates, Written Answers, 17 December 1925, Hansard.[/ref]. The first wave in 1918 was relatively mild and, as it was not a notifiable disease, in some places it passed by unnoticed.

During the second wave in the autumn, the severity of the outbreak was hard to ignore and the public health response, which happened on a local level, was to control entry to places of public gathering, namely theatres, cinemas, and dance-halls, and to isolate those who were ill. Many schools across the country were also shut at one time over the course of the three waves, commonly for a period of two weeks, which was then extended if required[ref]School reports for some select public schools can be found in FD 1/537: Schools reports on cases and treatment of influenza, 1919.[/ref]. This was enacted by the local Medical Officers of Health.

At the time, the branch of government that dealt with health was the Local Government Board; however, it tended to focus on the administration of the Poor Law and the health care of citizens tended to be left up to local authorities, with some guidance from the centre.

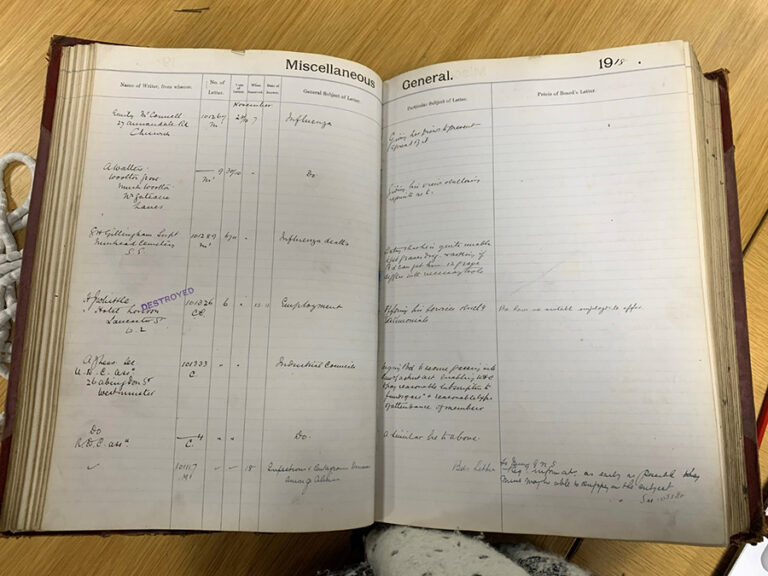

The indexes of miscellaneous local government correspondence found in MH 60 show that individuals and organisations wrote into the centre asking what the government intended to do about the outbreak. People offered up theories as to the reasons behind the transmission of the disease, including that it was spread by infected rats (letter dated 26 October 1918 from an anonymous Englishman); and spread by the foul air in the underground (letter dated 29 October 1918 from G W Buckthought).

Many medical practitioners thought the ’flu was caused by a bacteria called Pfeiffer’s Bacillus. There was, however, much doubt surrounding this theory as the bacteria was not found to be present in all cases. And indeed, we now know that the ’flu is not caused by bacteria but by a virus, which is much smaller.

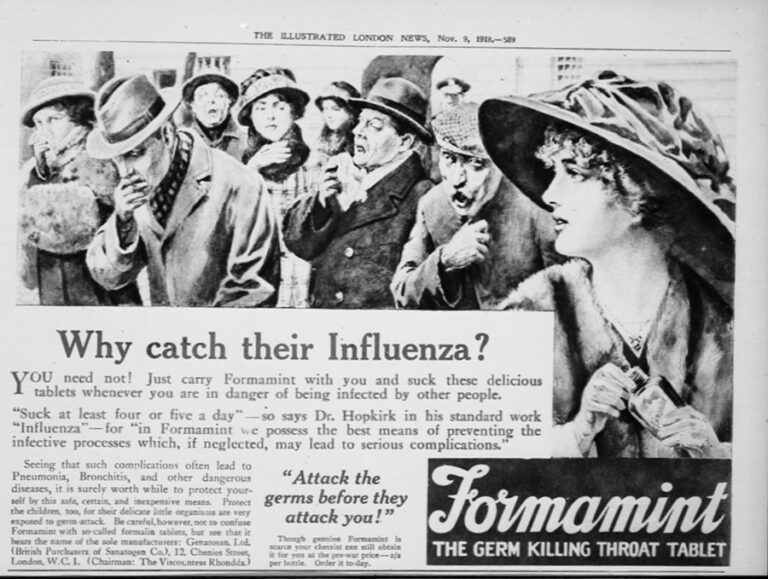

The unknowns surrounding the disease meant that there was a lack of consensus in the medical community about how best to treat the ’flu. The reality was that doctors were essentially powerless against the ’flu, able to only treat its symptoms, leading to a reliance on commercial remedies for prevention and treatment. Remedies included Condy’s Fluid, a branded version of permanganate potassium, as well as throat lozenges, medicated wines, and carbolic vaporizers. Individuals also wrote into the centre offering the government advice on how to treat the ’flu. One correspondent suggested consuming yellow brimstone (natural sulphur) in milk, noting their own brother had cured his wife with it (letter dated 29 October 1918).

Despite precautions some localities became overwhelmed with the number of fatalities. In the midst of the second wave of the ’flu, newspaper headlines like ‘Many Deaths’ and ‘More Deaths’ sadly became commonplace. On 29 October 1918 The Times wrote, ‘our obituary columns this morning bear melancholy witness to the ravages of the great plague of influenza and pneumonia’[ref]The Times, 29 October 1918, The Times Digital Archive.[/ref].

The MH 60 indexes show that the superintendent of Nunhead cemetery in South-East London wrote to the Local Government Board declaring he was unable to get sufficient graves dug. He requested that the Board supply him with 12 grave diggers and tools (letter dated 6 November 1918)[ref]Local Government Board, miscellaneous registers of correspondence, 1918-1919, MH 60/22.[/ref].

The end of the pandemic

Come November, the end of the war was nigh but sadly there was no relief from the ravages of the ’flu. The war diaries of the Director General of Medical Services reported that, in the week that peace was declared there were 7,409 cases of influenza reported in the Army, and the following week, ending 23 November, this had risen to 8,008. The War Diary shows the breakdown of infections across the formations of the army[ref]War Diaries, Branches and Services: Director General Medical Services, November 1918, WO 95/48/10.[/ref].

The final wave of the pandemic took place in the early months of 1919 and primary pneumonia and acute influenza pneumonia was made notifiable by temporary Public Health (Pneumonia, Malaria and Dysentery) Regulations 1919, over fears that demobilisation would cause an upsurge in cases.

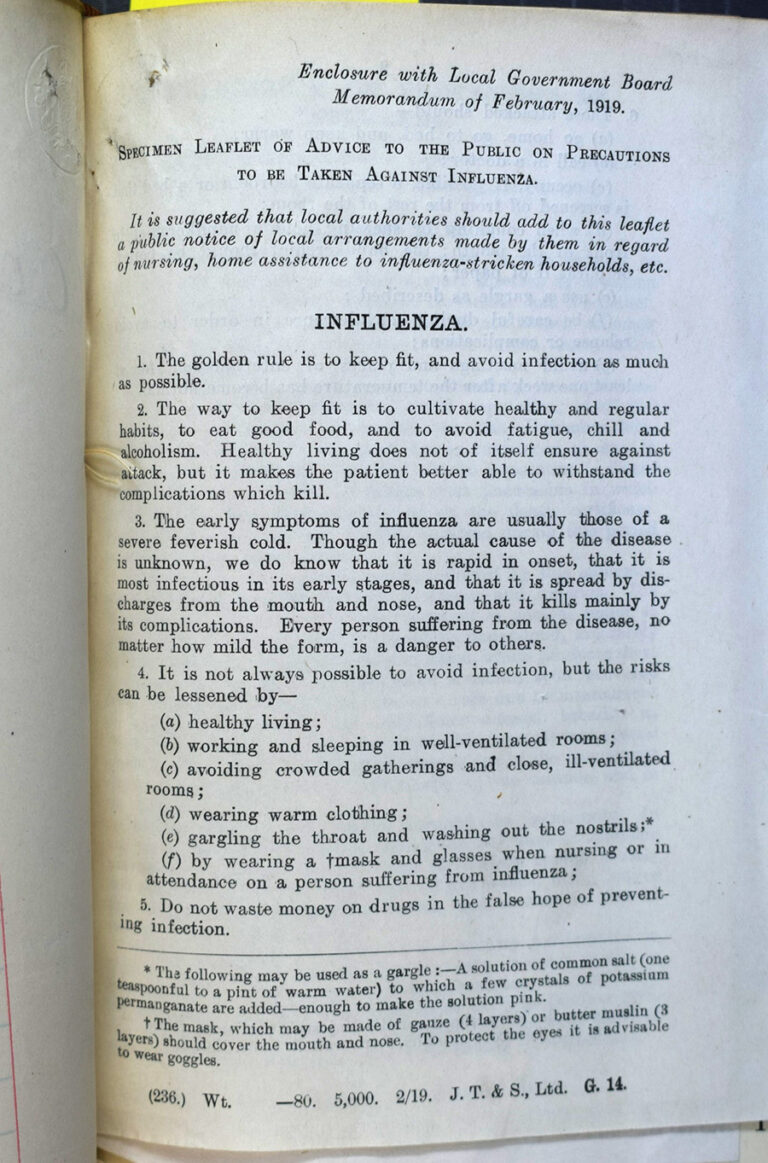

In February, when it seemed that the scourge of the ’flu would never go away, the Local Government Board cautioned citizens about the continuing menace through a circular sent out to local authorities, reiterating much of the advice that had been circulating already. Suggested measures included ‘wearing warm clothing’, ‘keeping fit’, and ‘avoiding crowded gatherings and close, ill-ventilated rooms’. It was recommended that people engaged in nursing the afflicted should wear goggles and a mask (made of four layers of gauze or three layers of butter muslin)[ref]Specimen Leaflet of Advice to the Public on Precautions to be Taken Against Influenza (February 1919), Local Government Board Circular Letters, Vol. 48 Pt. 1, 1919, MH 10/84.[/ref].

Arthur Newsholme, the Chief Medical Officer of the Local Government Board, also commissioned a film called ‘Dr Wise on Influenza’ which was a public information film that was circulated to local medical officers of health to show in their local cinemas[ref]Dr. Wise on Influenza (1919), BFI National Archive.[/ref].

The pandemic finally abated around May time, and the people of Britain could start rebuilding their lives.

Sadly, there were many cases of soldiers and workers from the front lines who survived the war only to fall victim to the influenza. The next blog will draw out some stories of service personnel, using records held at The National Archives found within our collection of First World War medical records in MH 106.

I came across around 20 fairly new-looking graves of Merchant Navy sailors in the San Michele Cemetery in Venice who all died around the same time in April, 1919. I don’t know whether this was a result of an accident to their ship or whether they all succumbed to the ‘flu pandemic. How would I find out more from here in Great Britain?

Dear Penny

Further enquiries could be made if you have the vessels name and registry via Lloyds of London as they detail shipping loss and accident. They also register loss of life and cause as they underwrite the Insurance of shipping.