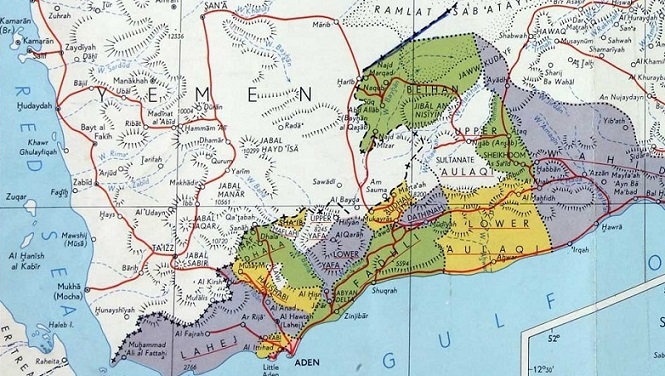

Detail of a map showing the Protectorate of South Arabia and the delineation of South Yemen borders (catalogue reference: FCO 8/370)

Wendell Philipps has often been described by the press as ‘America’s Lawrence of Arabia’, and by British diplomats as a real thorn in their sides. To quote from one of his books: ‘herein lies the story of a dream, which like many dreams occasionally achieved nightmarish qualities’. [ref]W. Phillips. ‘Qataban and Sheba. Exploring the Ancient Kingdoms on the Biblical Spice Route of Arabia’ New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1955. Preface.[/ref]

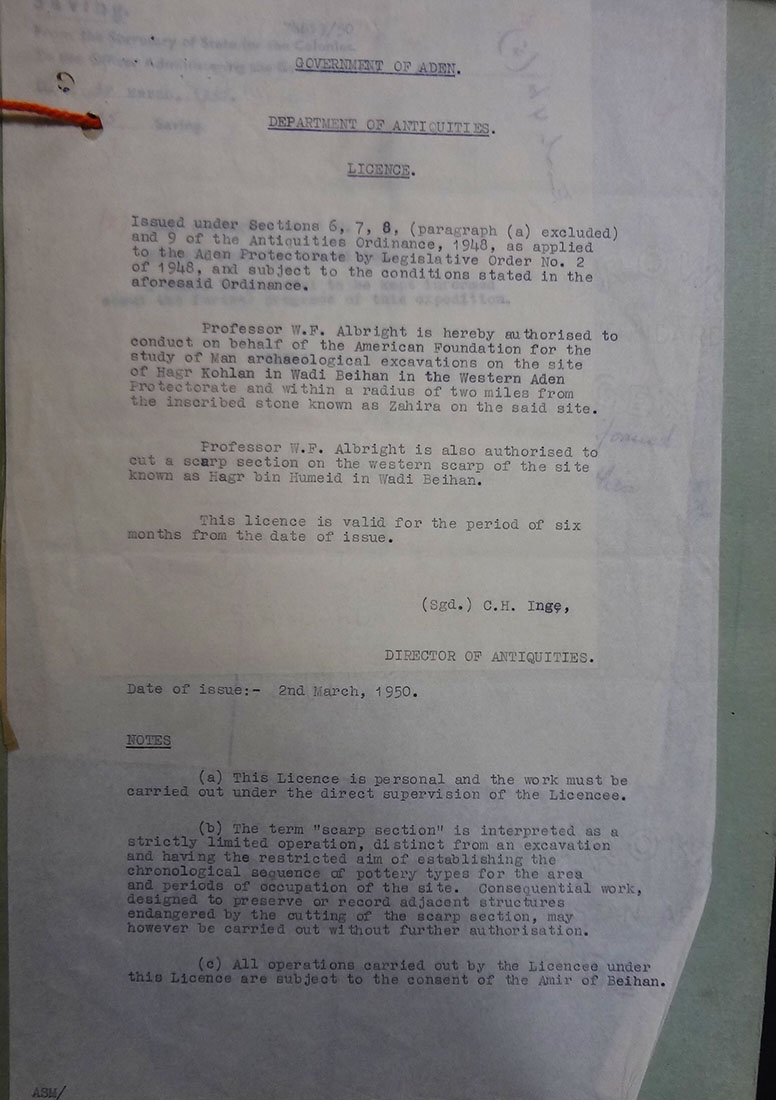

Wendell Phillips and his expedition, funded by the American Foundation for the Study of Man – which he had created the year before – arrived in Aden at the beginning of March 1950, and started excavating in the Beihan valley in April. There wasn’t much information about the site before Phillips started digging. The ancient Kingdom of Qataban, and its capital Timna, had been described by classical geographers; however, as Charles Inge, the Director of Antiquities recalled at the end of the season, up until then ‘information about the site was confined to the inexpert reports of Protectorate and Royal Air Force Officers’ (CO 537/6186).

All in all, Inge was satisfied by the progress made by Phillips, but he noted that, should the expedition wish to return on a larger scale, he would have to employ properly trained archaeologists. In June 1951, Inge put an end to the Beihan excavations after a second season. By that time, however, Phillips probably didn’t care that much. He had, very unexpectedly, been granted a concession to excavate at Ma’rib, in the western part of the Yemen – which he thought may have been the capital of the fabled Queen of Sheba. It was the very first time a foreigner was given such an authorisation by the King of the Yemen, Imam Ahmad bin Yahya. (FO 371/91261).

- Agreement between the Imam of the Mutawakilite Kingdom of the Yemen and the American Foundation for the Study of Man (catalogue reference: FO 371/91261)

It was a dream, obviously, but it was also when the nightmares began – for Phillips himself, but also for the British Officials who had to deal with him.

Ma’rib was in the Yemen, which wasn’t under British authority, but the only way to reach it was to drive through the Aden Protectorate. For this, custom duties had to be paid to the different chieftains whose territories were crossed. Phillips, however, wanted all his equipment, foodstuffs and supplies to be exempted from tax. As the Governor of Aden, Tom Hickinbotham, replied that only his archaeological equipment would be exempted, he telegraphed the British Prime Minister directly to get free passage through the Colony of Aden and the Eastern Protectorates (CO 1015/751).

- Phillips to Churchill, December 1951 (catalogue reference: CO 1015/751)

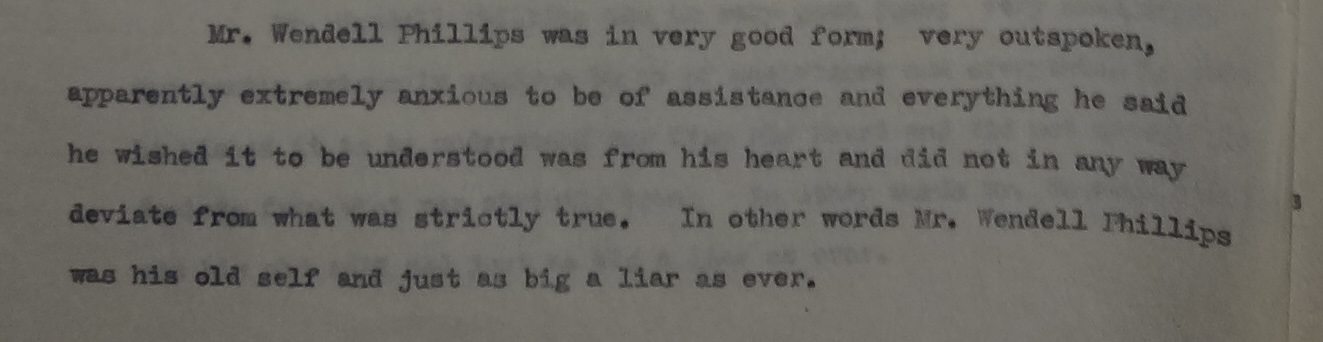

Phillips was very influential in Washington, and implied that the British authorities in Aden were making his life difficult on purpose because ‘they were jealous of his having obtained permission to excavate at Marib’. When Hickinbotham repeated that only his archaeological equipment would be exempted, Phillips replied angrily that ‘if [his] decisions were not favourable to him he was able at any time to have them over-ruled by using the influence of the important personages with whom he continually claimed acquaintance’ (CO 1015/751).

In January 1952, the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs was attacked on the subject in Washington by prominent Americans: Hickinbotham had to yield, ‘in deference to the Colonial Secretary’s anxiety to avoid a storm with the Americans over a comparatively minor matter’. Writing to Lambert at the Colonial Office, Hickinbotham made it very clear that he wasn’t happy with the decision. He felt that the ‘impoverished’ States were entitled to those custom duties which represented an important source of revenues, and that the whole affair was rather unfair, especially ‘in view of Phillips’ demeanour’.

Phillips’ attitude was not doing him any good in the Yemen either. Jacomb, the Chargé d’Affaires at Taiz, reported that he wasn’t very respectful of local sensitivities. He had been told not to bring gifts, but did so regardless, including a cheap kaleidoscope ‘not very different to those sold in San’a to the children’. He also telegraphed the Imam directly to obtain permission to enter the Yemen instead of going through the usual channels and applying for visas in Washington. This, and the fact that ‘the expedition [did] not seem to be very well equipped for the job’, led the Yemeni authorities to decide not to renew Phillips concession at Ma’rib. He would have to leave by 31 March 1952.

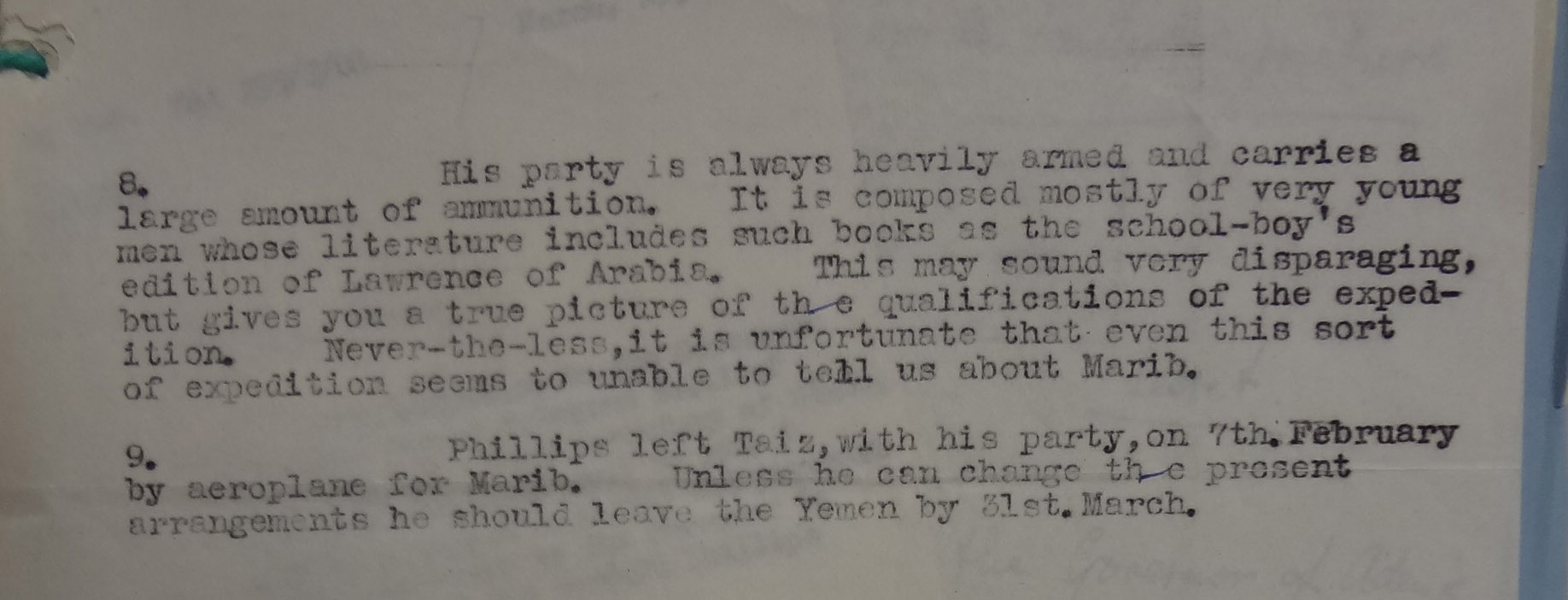

Recalling that it was, in fact, the ‘ineptness’ of the expedition which had led to the suspension of their authorisation to excavate in Aden, Jacomb wrote:

His party is always heavily armed and carries a large amount of ammunition. It is composed mostly of very young men whose literature includes such books as the school-boy’s edition of Lawrence of Arabia. This may sound very disparaging, but gives you a true picture of the qualifications of the expedition. Nevertheless, it is unfortunate that even this sort of expedition seems to be unable to tell us about Marib. (CO 1015/751)

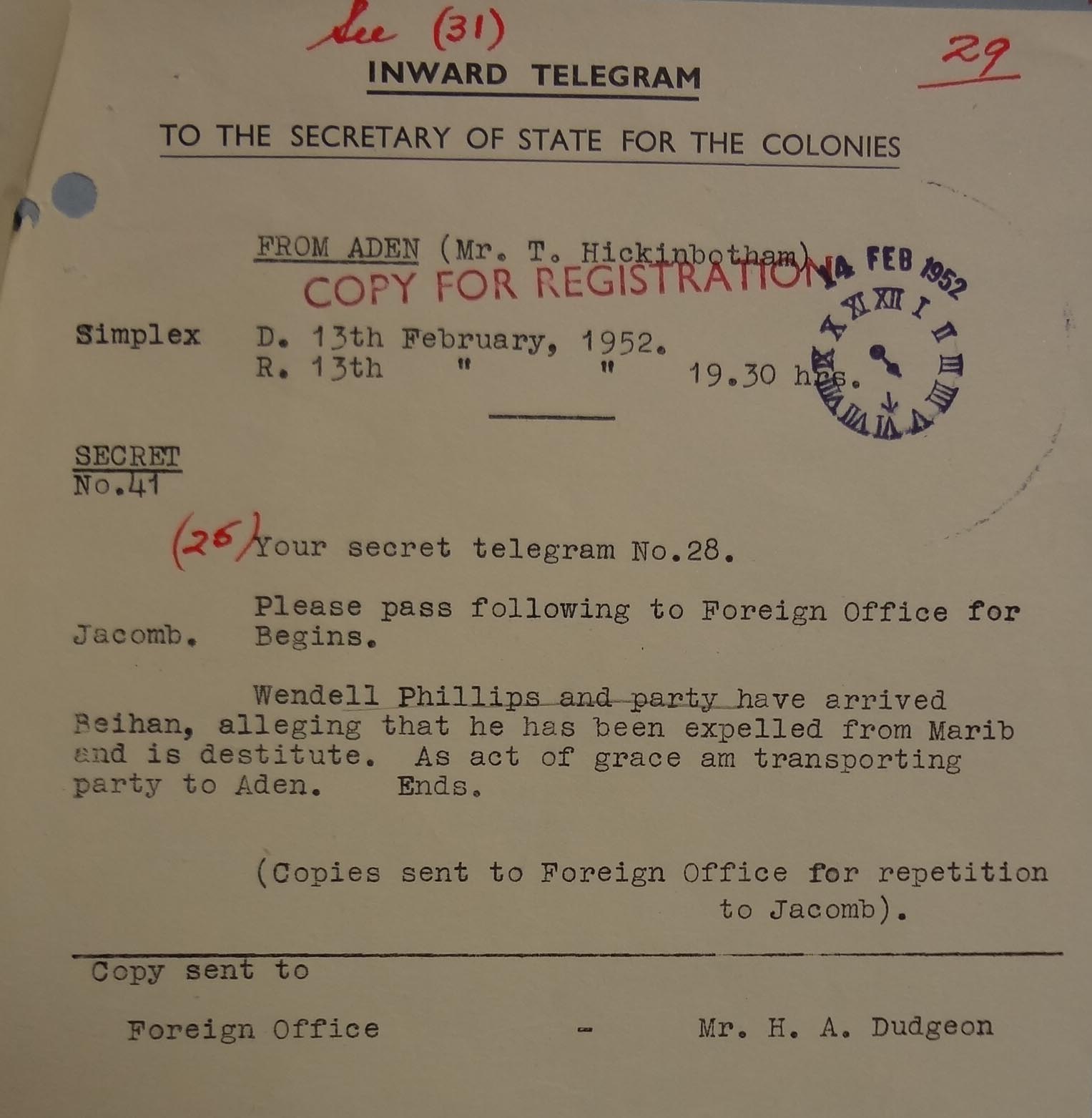

Just a few days after Jacomb sent this rather harsh assessment of the expedition, events took a dramatic turn. On 13 February, the Governor of Aden telegraphed: ‘Wendell Phillips and party have arrived Beihan, alleging that he has been expelled from Marib and is destitute. As act of grace am transporting party to Aden.’ (CO 1015/751)

What exactly happened at Ma’rib isn’t clear. According to Phillips, they had been harassed and detained by the soldiers guarding the site. His field director, he said, was beaten up; the whole expedition was kept awake at night by screaming soldiers and shots were fired. As a result, he said, they fled for their lives, with very little more than the clothes they were wearing. Jacomb reported:

When a vehicle started to leave at 2 a.m. one morning, shots were fired […] at its tyres to halt it. There was also an incident when the window of a vehicle was broken by the butt of a rifle and a muzzle was thrust in an American’s stomach. Apparently, at a different moment, a pet dog was killed in the room of one American. (CO 1015/751)

The Yemeni account of the story, unsurprisingly, is different. They conceded that soldiers were guarding the site closely, to make sure the members of the expedition were not stealing antiquities, and that some incidents had occurred. They denied all other accusations categorically. Phillips, they explained, had failed to comply with the terms of the agreement. He had not produced the requested documentation in time, and had not managed to gather enough experts; work had started eight months late and had been excruciatingly slow; various members of the expedition had misbehaved towards Yemeni official and labourers; and their ignorance had led to seven pillars of the temple of Balqis falling down. They added: ‘He has preferred to leave Marib in this suspicious manner to be able to smuggle […] some ancient and precious relics, to cover his incompetency and the failure of his mission.’ (CO 1015/751)

What we know for sure is that, on 12 February 1952, Phillips took the whole expedition, servants included, to the site and told the soldiers to dismount, as he wanted to take photographs. They fled in two lorries, leaving all equipment behind. The other thing Phillips left behind was a huge number of debts.

Understandably, the Imam refused to let anyone collect the equipment before those debts were settled. This was finally done a year later, when Phillips agreed on a sum to pay. The equipment was collected from the site and brought back to Aden, minus what the Yemeni Government had decided to buy for themselves: ‘a truck, a refrigerator, a deep-freeze machine, some cooking pots and a Coca-Cola machine’ (FO 371/104533).

The Foreign Office thought they were rid of Phillips, but he came back on their radar the following year, when he met with Hickinbotham in November 1954. He claimed to be the proud owner of several oil concessions, including one in Dhofar, in Oman; that he had been authorised by the Sultan of Muscat to negotiate a concession for the Gwadur territory of Muscat (now Gwadar, Pakistan); and that he had been appointed Director General of Antiquities in the Sultanate. Chauncy, at the British consulate in Muscat, commented: ‘The Sultan has a sense of the ridiculous […], I doubt if he would make any such appointment for Phillips.’ (FO 1016/361)

Notes of a meeting between Hickinbotham and Phillips, November 1954 (catalogue reference: FO 1016/361)

In 1955, Phillips enquired about the possibility of bringing an expedition to Dhofar in February 1956 and taking photographs in Aden on the way. This created a serious dilemma for Hickinbotham. On one hand, Britain was trying to ‘bring the Americans round to our way of thinking’ in the Gulf and, as a Foreign Office official put it, it was ‘not the moment to provoke a row with a highly influential American, however tiresome he [had] been in the past’. On the other hand, the Governor was trying to persuade the rulers to pool together their oil revenues. Phillips had made a fortune in the oil business, and couldn’t be trusted in the region as he was ‘a danger and unscrupulous’. Hickinbotham would probably have had to yield again if the Sultan of Muscat hadn’t withdrawn his invitation to excavate in Dhofar because of a border dispute with Saudi Arabia.

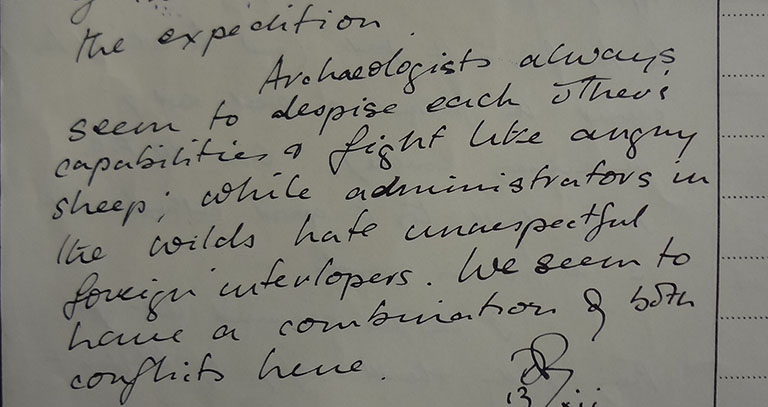

Whatever we think of Wendell Phillips, his methods and his achievements, I think we can conclude, with D M Riches, of the Eastern Department of the Foreign Office:

‘Archaeologists always seem to despise each other’s capabilities and fight like angry sheep; while administrators in the wilds hate unrespectful foreign interlopers. We seem to have a combination of both conflicts here.’ (FO 371/114571)

Minute by D M Riches, 13 December 1955 (catalogue reference: FO 371/114571)

Thank you for this entry. I looked into the archives in London for my research project on the ongoing (and past) situation in 2017. One of the other irritating correspondence bits I noticed in a letter from W. Phillips from February 22, 1963 presenting himself to the Commissioner’s Office when trying to get another concession for work in the field: “I am now the only European (sic!) explorer to have studied the three great capitals of Timna, Marib and Shabwa.” Interesting and important archive materials. Thank you for highlighting.

Seems like the typical British field lackey Hickinbotham was insanely jealous of Wendell Phillips, and was further incensed by Wendell’s victory in the first round. Outmatched, outplayed and embarrassed, Hickinbottom continued to make pathetic attempts to thwart the most accomplished American archeologist in history.