Today marks 50 years since the 1970 Equal Pay Act received royal assent – a significant moment in the history of women’s rights in the UK. While the battle for equality continues, this was a defining moment.

This was the first piece of UK legislation:

‘to prevent discrimination, as regards terms and conditions of employment, between men and women.’

The Equal Pay Act 1970 – https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1970/41/enacted

Essentially the right to equal pay for equal work.

Women had long been campaigning for equal pay; in the suffrage era, many women saw the vote not as an end in itself, but as a way of influencing the government on issues that were important to their lives. Pay equality was key, especially to working class women.

When Suffragette Alice Hawkins went to the Treasury as part of a deputation of suffrage supporters in 1913, she said, ‘Women have been trying to get the vote in order to alter their status in life'[ref]Women’s Suffrage: deputation from Working Women Suffragists. Catalogue ref: T 172/110.[/ref]. In her testimony to Lloyd George she spoke about her experience in the boot and shoe trade in Leicester:

‘The wages of women are very much less than the wages of men. We feel that very keenly in our Trades Union, because many of our women do exactly the same work as the men and we claim we ought to have exactly the same pay.’

From the testimony of Alice Hawkins. Catalogue ref: T 172/110

There have been constant demands for equal pay throughout the 20th century. Indeed, in the First World War equal pay for equal work was promised, if not actually realised, to female munitions workers, in part to protect post-war male wages[ref]The famous circular ‘L.2’, with its promise of ‘equal pay for equal work’ was issued in October 1915. /equal-pay-equal-work-female-munitions-workers/.[/ref]. In the 1930s, the Six Point Group, a women’s rights organisation, lobbied the government around six principle issues, one of which was ‘equal pay for men and women teachers’[ref]Extract of a letter from the Six Point Group regarding equal opportunities for men and women in the Civil Service, detailing their six organisational aims. Catalogue ref: CAB 27/226.[/ref].

So why the change?

Momentum had been slowly building and in 1964, the Labour government had been elected on a manifesto that included equal pay. However, the strike by women at Ford Motor Company’s Dagenham plant in 1968 added to the pressure on government and acted as a significant catalyst for greater change.

In a regrading exercise at the motor plant, the women’s work had been graded as less-skilled than the men’s, and therefore they were paid less. Frustrated with the situation, the women withdrew their labour. As the strike continued, production of the seat covers stopped. Prime Minister’s office files describe how the strike threatened complete closure of all Ford plants in Britain affecting 40,000 men[ref]Read more about National Archives records on the blog ‘Fighting a great fight: Women workers at Ford Dagenham’: /fighting-a-great-fight-women-workers-at-ford-dagenham/[/ref]. The actions of these women was having a vast impact on the motor industry and the economy.

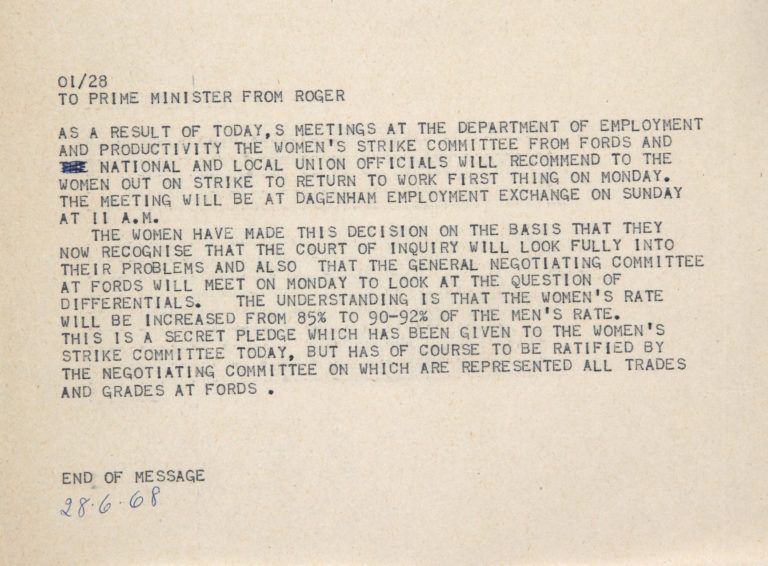

Government telegrams show the fraught behind-the-scenes conversations. Three weeks into the strike Barbara Castle, First Secretary of State and Secretary of State for Employment, was sent to intervene in person, which was significant in itself. Through a process of negotiation, it was decided the women’s rate was to be increased from 85% to 90-92% of the men’s rate.

The women workers settled for this agreement. While they did not win their specific demands, they had succeeded in putting huge pressure on the government and giving equal pay a spotlight.

The following years saw union membership grow fast among women and the government feared further industrial action around pay.

Behind the scenes

In the aftermath of the Ford machinist strikes Castle noted that, of the seven items listed in the chapter on workers’ rights in the Labour 1964 manifesto, equal pay was the only one on which ‘no move had yet been made’[ref]Conclusions of a Meeting of the Cabinet held at 10 Downing Street on 4 September 1969 at 15:00. Catalogue ref: CAB 128/44/42.[/ref]. In August 1969 It was estimated that of 8.5 million female workers, only 1.5 million had equal pay[ref]Equal Pay memorandum by the First Secretary of State and Secretary of State for Employment and Productivity, Barbara A Castle. 28 August 1969. Catalogue ref: CAB 129/144/13.[/ref].

Cabinet papers show some of the conversations that were happening at the heart of government. Castle repeatedly presented on this issue of equal pay to the rest of the cabinet. Her support for equal pay was clear, but also delicately delivered and carefully thought out. She was cautious to not associate herself with past feminist campaigns but rather present a pragmatic and economically sensitive argument for equal pay.

‘Expectations have been raised’

The issue of equal pay was becoming inevitable. Industrial action, such as that by the women at Ford put vital pressure on. The government worried that if they didn’t act on equal pay it, the issue would be forced by sporadic strikes.

Castle relayed to the Cabinet:

‘Pressure for equal pay was mounting steadily and it was clear that trade union leaders could not resist it even if they wanted to. Employers would increasingly be compelled to concede equal pay in the course of normal pay negotiations and the Government now had to decide whether to let equal pay come as a result of sporadic action or as a controlled operation in which the economic disadvantages were minimalised.’

Barbara Castle in the conclusions of a meeting of the Cabinet, 4 September 1969. Catalogue ref: CAB 128/44/42

Castle also noted, the government may ‘be storing up industrial trouble for ourselves’[ref]Equal Pay memorandum by Barbara A Castle. 28 August 1969. Catalogue ref: CAB 129/144/13.[/ref].

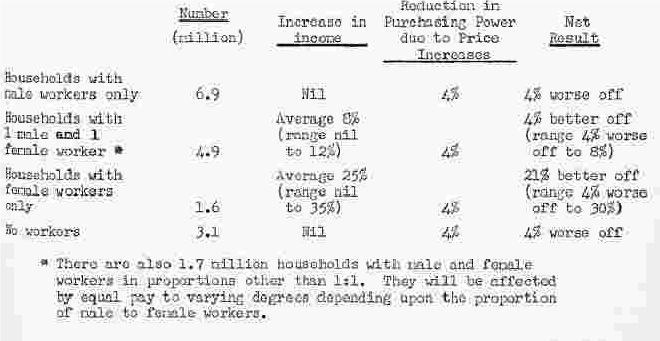

The costs of equal pay would have implications for the economy and household incomes; the price of introducing equal pay depended on the timing and definition used. However, it was anticipated that it would add to the national wage and salary bill by approximately 5%[ref]Conclusions of a Meeting of the Cabinet, 4 September 1969. Catalogue ref: CAB 128/44/42.[/ref]. A significant concern was the impact of equal pay on wages in general, employers would need to pay for it somehow and it was feared it would drive men’s wages down, particularly for the some of the lowest income families. Trade Unions were hesitant in their support. Presenting to the Labour Cabinet Castle said, ‘The introduction of equal pay, however desirable, was not so urgent a social reform as the raising of the wages of the lowly paid.’[ref]Equal Pay memorandum by Barbara A Castle. 28 August 1969. Catalogur ref: CAB 129/144/13.[/ref]

The economic and social implications of equal pay for women were investigated in depth by the inter-departmental group on equal pay for women and the TUC was consulted. Cabinet papers noted the concerns that industries wholly or mainly dominated by women were likely to stay at a low rate of pay. Many of the lowest paid women were likely to benefit least from equal pay, such as the female-dominated services industry. Legislation would not address the historic undervaluing of women’s work. These discussions also show an underlying sexist assumption that women were less efficient workers, and that equal pay would force women to deliver work of an equal standard to men’s work[ref]Equal Pay memorandum by Barbara A Castle. 28 August 1969. Catalogue ref: CAB 129/144/13.[/ref].

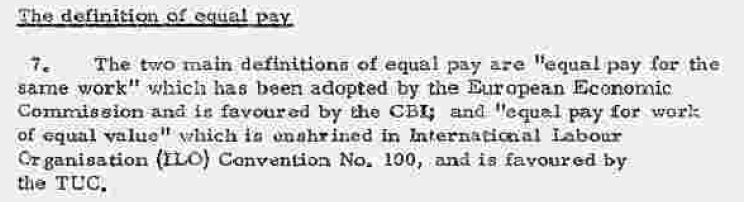

Ultimately, the economic concerns led to the final terms of the act. Different definitions of equal pay were considered, but eventually the act addressed equal pay for ‘equal work’, not equal pay for work to be considered of equal value[ref]This was considered to be more ambitious, difficult to define and ultimately more costly.[/ref].

While today is the anniversary of the act receiving royal assent, the law would not come into force until the end of 1975. In theory this was to give time for rates of pay to be adjusted and financed; in practice it also gave employers time to adjust job descriptions, which would create a loophole for continuing different rates of pay[ref]Reflection on the Acts limitations by historian Cathy Hunt: https://cathyhunthistorian.com/2020/05/26/dont-try-to-be-sexy-ms-smith-equality-in-the-1970s/.[/ref].

The decades of campaigning had brought the fight for equal pay the visibility it needed and forced the issue in the heart of government. The final act was limited in scope, but gave hope to women for further future change.

Equal pay was only valid as long as women did exactly the same jobs as men, so for example if women didn’t do lifting of boxes or repair cars then the pay that men received for such pay should not be equalised. There is of course an ongoing battle for equality, like men not being allowed to be midwives and excluded from legislation.