‘There can be no doubt that with regard to two of the defendants they have been in the habit of presenting themselves in public sometimes in the character or disguise of women, and at other times in the own habiliments in the dress of men, but still under circumstances which produced a public scandal by their assuming the gait, and manners, and carriage, and the appearance of women, with painted and powdered faces, so as to produce a general impression, though in male attire, that they were of the opposite sex.’

TRIAL OF BOULTON AND PARK (Lloyd’s Illustrated Newspaper, Sunday 21 May 1871, 8) (British Library Newspapers)

It has been 150 years since the trial of The Queen v Boulton and Park, yet the lives of these individuals, the sensational trial that followed their arrest, and the documents detailing the events are still relevant to us today. In this post, published during LGBT History Month, I will be discussing what we can learn from Thomas Ernest Boulton and Frederick William Park, better known as Fanny and Stella, and the importance of archival materials in understanding and highlighting diverse histories such as theirs. I will call them Fanny and Stella throughout.

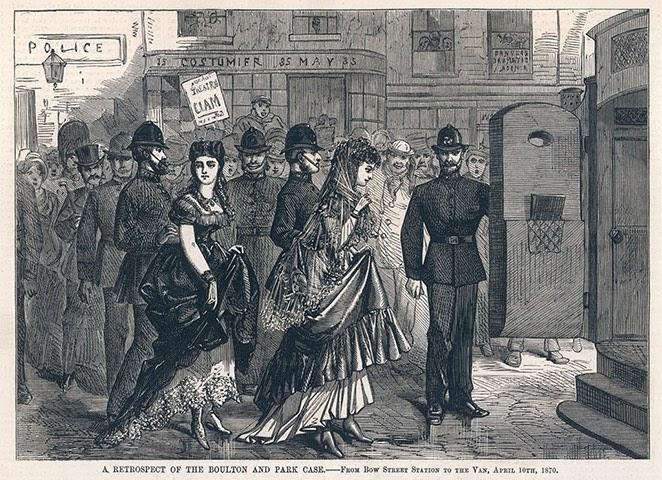

In April 1870 at London’s Strand Theatre, Mrs Fanny Graham and Miss Stella Boulton were arrested and subsequently charged with ‘commit[ing] the abominable crime of buggery’[ref]p.35 McKenna, ‘Fanny and Stella: The young men who shocked Victorian England’ (Faber, 2013)[/ref], conspiring ‘to induce and incite other persons feloniously with them to commit said crime’, and ‘disguis[ing] themselves as women and frequent[ing] places of public resort, so disguised, and to thereby openly and scandalously outrage public decency and corrupt public morals’.

This was not a solitary incident, for the two were known throughout the mid- to late-19th century for their cross-dressed pursuits on the streets and the stage. As part of a theatrical troupe the duo toured the South East of England as Boulton and Park performing ‘Fanny and Stella’. But, as Morris B Kaplan notes, ‘Fanny and Stella wandered off of the stage and outside the confines of a sexual underworld’[ref]p.47 Kaplan, ‘Men in Petticoats’ (Imagined Londons, ed. Pamela K Gilbert, SUNY Press, 2012)[/ref]. ‘Parad[ing] openly on the streets of central London, they challenged conventional assumptions about gender and sexuality, respectability and transgression, business and pleasure’[ref]p.47 Kaplan, ‘Men in Petticoats’ (Imagined Londons, ed. Pamela K Gilbert, SUNY Press, 2012)[/ref]. In fact, in court it was revealed that Fanny and Stella’s reputation offstage had led to them being placed under surveillance for over a year before their eventual arrest.

A year later, following a sensational six-day trial, a jury found Fanny and Stella not guilty and the two were acquitted. In their reporting of the case, the Lloyd’s Illustrated Newspaper notes that ‘Boulton fainted upon the verdict being returned, and upon his recovery the prisoners left the court with their friends’ (Sunday 21 May 1871, p.8). The transcripts from the trial are held at The National Archives (DPP 4/6) along with records relating to the copyright of images of the duo, as well as depositions and letters that were included as evidence (KB 6/3). It is rare that such transcripts survive; the trial records give a unique insight into how the trial played out in court.

While for Fanny and Stella their trial ended in the best possible way, their ‘not guilty’ verdict is believed to have inspired a damning change to the law in 1885 called the ‘Labouchere Amendment’. Infamously convicting both Oscar Wilde and Alan Turing, the Labouchere Amendment ensured that in instances in which ‘sodomy’ could not be proven, an individual could still be charged with gross indecency. In this instance, Fanny and Stella’s clothes, their demeanour, their names or even how they were perceived by society could lead to their arrest and conviction.

Sadly, it is all too common to find traces of LGBT history among the legal documents and newspaper articles that documented alleged ‘crimes’ such as Fanny and Stella’s. Laws and attitudes have changed significantly in the 150 years since their court case, and this is precisely why archival material such as trial transcripts are important to us today, for they demonstrate the prejudices and injustices of the past.

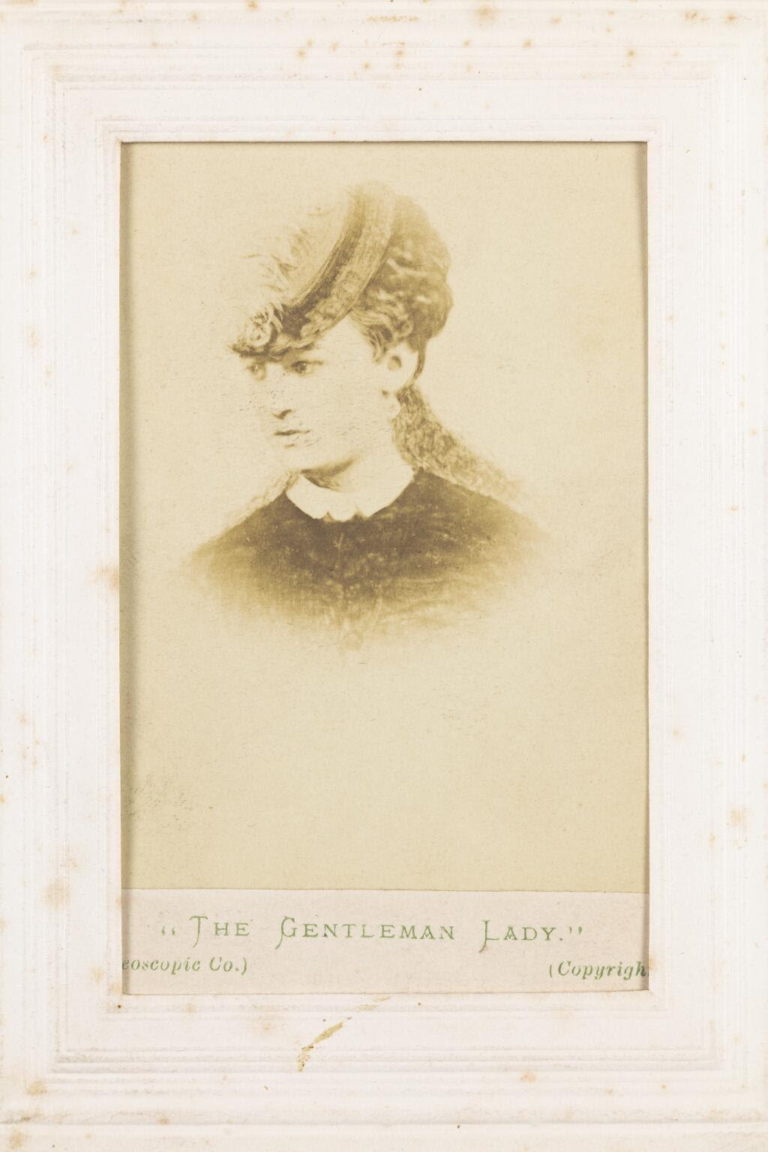

Newspaper reports, images of Fanny and Stella, and The National Archives’ records are also extremely important, for they highlight the ways in which individuals experienced gender and sexuality in non-heteronormative ways, especially during a time which we still regard as being renowned for its rigid gender roles and strict social ideals. Archival materials allow us to piece together the lives of these individuals, as Neil McKenna has shown in his semi-fictional biography ‘Fanny and Stella: The young men who shocked Victorian England’ (2013).

‘The clerks who recorded the proceedings got into a terrible muddle, littering their transcripts with crossings-out and corrections, turning ‘he’s’ into ‘she’s’ – and vice versa. The witnesses were equally confused, stumbling and tying themselves in linguistic knots.’

McKenna, ‘Fanny and Stella: The young men who shocked Victorian England’, p.35

Newspaper reporters, court spectators and the clerks were all unsure of how to refer to Fanny and Stella. As Neil McKenna observes, the trial transcripts are littered ‘with crossings-out and corrections, turning ‘he’s’ into ‘she’s’ – and vice versa’[ref]p.35 McKenna, ‘Fanny and Stella: The young men who shocked Victorian England’ (Faber, 2013)[/ref]. For some, the duo’s identities were baffling. Others found them to be an entertaining spectacle, which helped after the trial as the two began to tour Britain once more as a theatrical act. But of course there were those that were more hostile and less accepting, evident in the change of law some 15 years later.

Even today, continued and emerging research demonstrates that Fanny and Stella’s identities were likely more complex than men choosing to cross-dress. Simon Joyce’s article for Victorian Review explores ‘The Fanny and Stella Trials as Trans Narrative’, noting that it is ‘crucial to recognize that even though the 19th century had no single term that could serve as an equivalent to “transgender” today, there were nonetheless historical people who affirmed themselves and what we would term their gender identity in a context not only of public and legal hostility but also of surprising sympathies’[ref]p.98 Joyce, ‘Two Women Walk into a Theatre Bathroom: The Fanny and Stella Trials as Trans Narrative’ (Victorian Review, Vol 44, No 1, Spring 2018)[/ref].

Despite preconceived notions of the 19th century as being a time defined by gender binaries (male and female, husband and wife, public and private), Fanny and Stella reveal that individuals were still living their lives differently.

And the two were not alone – in fact six others were facing the same charges (three of which had absconded, and one sadly died). Records also detail the fervent support that Fanny and Stella received from friends who may have also been a part of a Victorian queer culture, with newspaper reports and transcripts describing the immense cheers that echoed throughout the court following their acquittal.

The Foreman: ‘Not guilty’ (loud cheers, drive of Bravo!”) ― His Lordship: ‘Upon all the counts of the indictment?’ ― The Foreman: ‘Yes, my lord. Not guilty on all the counts’ (renewed cheering, which was, however, soon suppressed).

TRIAL OF BOULTON AND PARK (Lloyd’s Illustrated Newspaper, Sunday 21 May 1871, p. 8) (British Library Newspapers)

Documents relating to the trial demonstrate the difficulties that were faced by LGBTQ+ Victorians, while simultaneously highlighting that these individuals existed. And while we can’t say for certain how Fanny and Stella may have identified, what we do know allows us to piece together a rich and diverse history, one that provides visibility for historical LGBTQ+ lives.

A wonderful article, so informative and enlightening. Thanks so much for sharing.

Archives forever 💖