This blog is published as part of Disability History Month (22 November to 22 December 2019).

Contemporary definitions, diagnoses and cures for the neurological condition commonly known as falling sickness in the early modern period, and now known as epilepsy, were subject to development and change as the Renaissance was succeeded by the Enlightenment, reflecting broader changes in theological and scientific thinking.

The approach to the illness was complex as it manifested itself with what were perceived as both physical and psychic symptoms. Also, scepticism grew over the belief that epilepsy represented demoniacal possession, with the causes of the disease increasingly viewed as naturally derived and potentially capable of being cured with natural substances.

The term ‘epilepsy’ was in use, but the seizures known as ‘falling sickness’ were also described as the ‘falling evil’, ‘grand mal’ or – harking back to antiquity – ‘the sacred disease’. The conditions identified as such could often include other convulsive conditions or cases where the senses were distracted.

The natural causes of the disease were debated extensively. Various explanations were proposed including rising vapours within the body; black bile and other bad humours; elemental similarities to thunderstorms; and excessive pride (leading to a fall).

The possible cures for the falling sickness were also wide-ranging and varied in their availability. The hermetic physician, Paracelsus, recommended mistletoe, blood from a decapitated man, pieces of the human skull, preparations of gold and coral or spirit of vitriol (now known to contain ether). Another treatment, based on the doctrine of signatures (which used herbs which resembled particular body parts to heal those parts), was powdered soap-wort seed, offered for three months at the time of the new moon; this was a substance which frothed when rubbed in water.

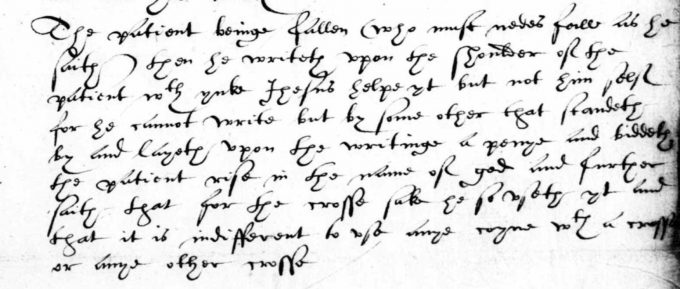

The case of wandering quack, James Middleton, gives an example of the continued use of supernatural treatments in the 16th century. Middleton was interrogated in Lichfield in 1587 for declaring himself to be a Stuart, descended from Scottish kings, and endowed with the ability to cure the falling sickness. His interrogators heard ‘upon his owne bragge that he could cure those diseases without phisicke or Surgery, but yet by godly meanes’ but when putting this claim to the test he failed to cure the patient. Under questioning, Middleton described the detail of his approach which involved prayers, striking the patient with ‘a little wande’ and then writing upon the shoulder of the fallen patient with ink ‘Jesus help it’ and lying a penny on the writing.

Detail from the report on James Middleton’s manner of curing the falling sickness. Catalogue ref: SP 12/206, f 93

A case heard in the Court of Star Chamber in 1622 hinged upon the effects of falling sickness and gives us another example of popular remedies. Alice Woodrowe sued Dorothy Crispe, alleging that her late son, a mercer of Cheapside, who had been staying at Crispe’s house in order to be cured of the falling sickness, had been married to Crispe’s daughter immediately after suffering a fit and while not in his right mind. Crispe denied the charge but explained that she had helped Thomas to reduce the number and duration of his fits, so they occurred no more frequently than five or six days apart and lasted no longer than an hour. After a fit had ended, she claimed that he was ‘sadder and not of so merry cheer’ for up to 12 hours, but was not ‘void of understanding’ once the fit was over. The plaintiff accused the defendant of carrying out incantations and of hanging spells around the neck of Thomas, but Crispe said she only administered remedies she had used with other patients, which included a bag of roots hung round his neck.

Extract from answer of Dorothy Crispe. Catalogue ref: STAC 8/295/13

Public attitudes to the falling sickness could vary greatly. Although usually viewed as a negative affliction, there was also a thought that the condition was associated with genius or greatness. It was popularly understood that Julius Caesar was epileptic and Shakespeare drew attention to this in his eponymous play. Hercules and the Emperor Charles V were also understood to be epileptic.

The 16th-century Dutch physician Levinus Lemnius wrote that falling sickness was evidently caused by the motion of the humours and ‘that men may not fear so much, when they see their mouths draw awry, their cheeks swoln, and strutting forth with a frothy humour: and should not be dismaid to come near them, and lend them their help’. This was particularly important because he thought some sufferers were buried alive because people were scared to check for vital signs, but ‘…some have broken the Coffin, and lived again’.

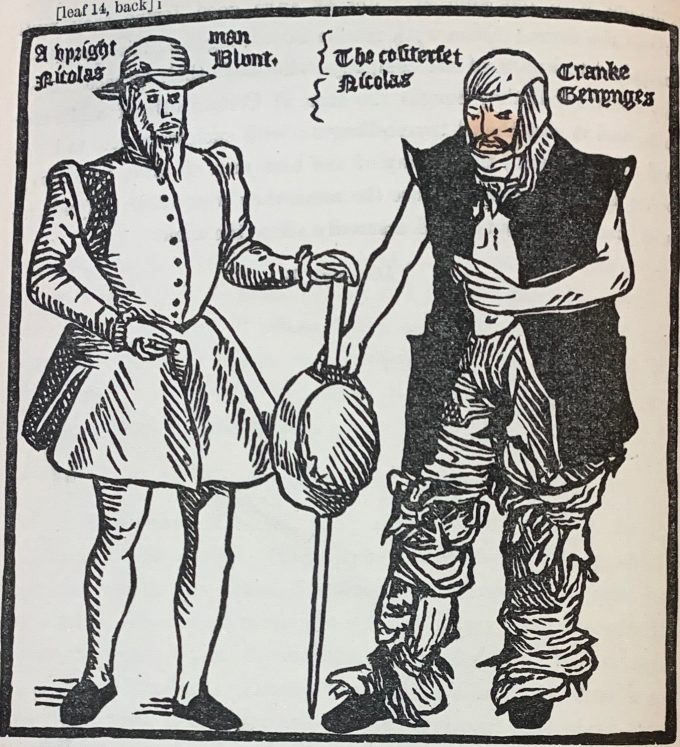

The falling sickness also produced compassion in some observers and it was believed that some people took advantage of that by faking fits in order to beg for money. Known as ‘counterfeit cranks’ and dressed with padding to protect their limbs during fake seizures, these beggars were described by Thomas Harman in 1567[ref]Thomas Harman, ‘A Caueat or Warening for Commen Cursetors vulgarely called Vagabones’, ed. E Viles and F J Furnivall, Early English Text Society, 1869, p. 50[/ref]. He wrote,’These that do counterfet the Cranke be yong knaues and yonge harlots, that depely dissemble the falling sicknes’, explaining that ‘crank’ was beggars’ cant for the disease.

Comparison of an ‘upright man’ and a ‘counterfeit crank’ from Thomas Harman’s Caveat on Vagabonds

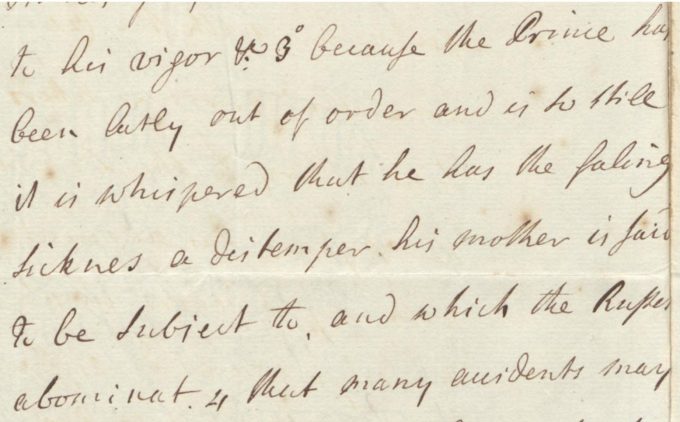

Attitudes may have varied between countries. In this letter of 1733 from a British representative in Russia to the Secretary of State in London, the likelihood of a marriage between the Prince of Bevern and the Princess of Mecklenburg was said to be undermined by a number of factors, not least that the Princess did not like the Prince. One of the other drawbacks listed was that ‘it is whispered that he has the faling sicknes a distemper his mother is said to be subject to, and which the Russes [Russians] abominat[e]’.

Extract from letter from Lord Forbes to Lord Harrington, dated St Petersburg 12 September 1733. Catalogue ref: SP 91/15, f 70v

The early history of the falling sickness is a fascinating one with a deep connection to the history of ideas. As a condition, it had a place within popular culture as well as within medical handbooks and it therefore features in many of The National Archives’ records, from petitions and court cases to diplomatic correspondence.

Further reading

Owsei Temkin, ‘The Falling Sickness: A History of Epilepsy from the Greeks to the Beginnings of Modern Neurology’ (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971 (2nd ed, revised))

thank you for this blog