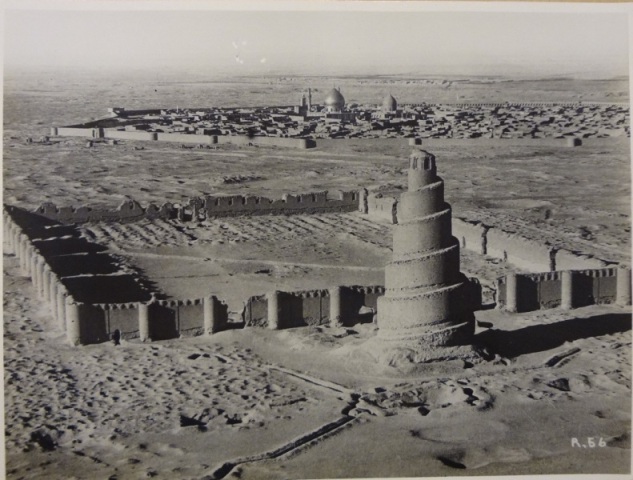

In my last blog, I mentioned antiquities discovered in Samarra that became the centre of a dispute between museums in England and the Mesopotamian authorities. At the same time, Britain was also squabbling over other Mesopotamian antiquities, unearthed by German archaeologist Walter Andrae and his team in Assur, in what is now Northern Iraq. The story of these antiquities, which took 12 years to reach Berlin from Basra, is a rather convoluted one.

When the excavations stopped in 1914, and as the Ottoman authorities had agreed to a division of the finds, Andrae packed about 700 boxes and set for Baghdad where the final division was to take place. Some artefacts were transferred to Constantinople and the remaining 448 boxes were loaded on board SS Cheruskia, supposed to take them to Hamburg, then Berlin, from Basra.

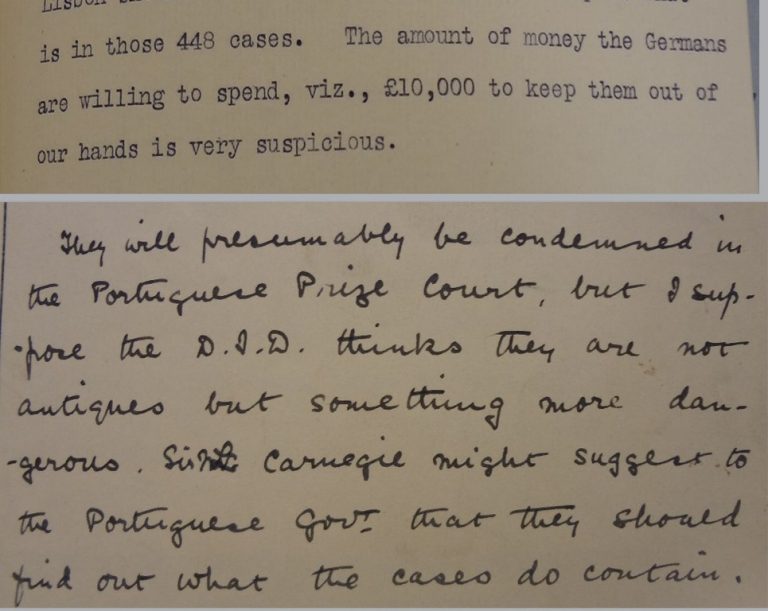

The Cheruskia left Basra on 27 June 1914 and, due to bad weather and technical difficulties, arrived in Portugal after the declaration of war. As the country was still neutral, it sought refuge in Lisbon. In January 1915, Germany attempted to transfer the boxes on board Danish SS Finlandia, which led the Intelligence Division to believe something much more sinister than Mesopotamian antiquities may be in those cases: ‘the amount of money the Germans are willing to spend, viz., £10,000 to keep them out of our hands is very suspicious.’

The Portuguese seized the ship in April 1916, and the Foreign Office instructed the British representative at Lisbon to find out what the cases actually contained (FO 372/873). In November 1916, eight random cases were opened and ‘found to contain most carefully packed various archaeological objects apparently coming from excavations in Assyria and Mesopotamia’ (FO 372/874).

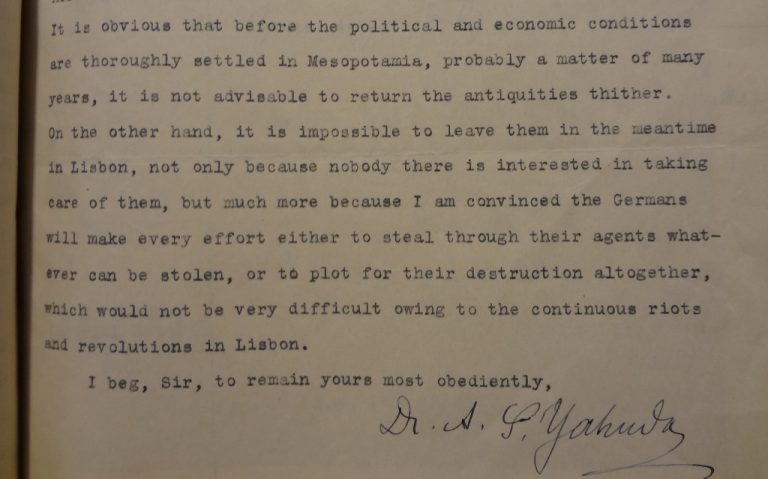

In July 1919, Dr AS Yahuda, a British national and a Professor at the University of Madrid, enquired about these antiquities which, he said, he had heard of while lecturing in Lisbon in 1916. He suggested ‘a small commission including an Assyriologist’ should go to Lisbon to examine the antiquities and ‘prepare the ground for negotiations with the Portuguese Government’ so that the objects could be transferred to London until they could be returned to Mesopotamia. The Foreign Office remained cautious, one official noting: ‘I cannot see how HMG or the future Government of Mesopotamia can have any legal claim to them.’

In August 1919, the Portuguese Minister of Finance declared that the antiquities should remain in Portugal if the National Society of Fine Arts decided it made sense. A legal adviser to the Foreign Office warned that if the antiquities had been condemned as prize, they legally belonged to the Portuguese Government, irrespective of their earlier history (FO 608/82).

It was agreed that ‘any overt action by His Majesty’s Legation would tend to excite Portuguese susceptibility’ and that Yahuda should be sent on a mission to have ‘discreet conversations with Portuguese scientists’.

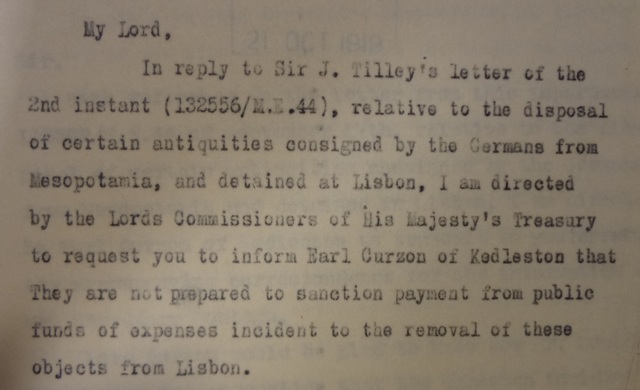

The main question then was – who would fund such a mission? Sir Frederick Kenyon, the Director of the British Museum, thought the Foreign Office should pay, but said the British Museum would refund them should they eventually acquire the objects. In October 1919, however, the Treasury made it clear that they were ‘not prepared to sanction payment from public funds of expenses incident to the removal of these antiquities’. In November, they finally agreed that the Mesopotamian authorities could fund the mission ‘provided that the amount involved was not unduly large’. Yahuda didn’t ask for more than his expenses, with a maximum of £400 which Treasury Officials immediately questioned as ‘very high’. In the end, the expenses amounted to a total of £114.17.6 – even the Treasury was satisfied (T 161/5/6).

While the Foreign Office, India Office and Treasury were arguing about who should pay, Walter Andrae wrote a passionate letter to Gertrude Bell, explaining that he feared the scientific value of the objects would be lost if he didn’t examine them himself. He wrote:

‘I know very well that after the conclusion of peace, we Germans are not able to raise any claim for us. But perhaps we could rely on the help of some people of fair international reasoning in regard to scientific things.’

Bell wrote back from Baghdad in March. She had met Andrae in Mesopotamia in 1909 and 1911, and had described him to her mother in rhapsodic terms. Her reply, however, had a curt, administrative tone: she was clearly writing as a colonial officer. She pointed out that ‘considerations based on “fair international reasoning” would cut both ways’ and added:

‘I have reason to believe that you have in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, certain moulded bricks of the 14th century inscription from the Liwan in the courtyard of the Marjan mosque in Baghdad. I know that these were removed by the Germans here during the war and I hold that on fair international reasoning they should be returned to the mosque where the remainder of the inscription at present exists.’

Hardly friendly (FO 371/5186).

In the meantime, Yahuda was struggling to obtain leave from the University of Madrid. ‘Here in Spain,’ he wrote as an apology in February 1920, ‘one can never get rid of the eternal “mañana” which very seldom is identical with the day of tomorrow’. He finally made his way to Lisbon in March 1920 with a view to ‘finding out the nature of the Mesopotamian antiquities’ and ‘inducing the Portuguese to give them up in favour of Mesopotamia.’

Yahuda admitted in his report, submitted to the India Office on 20 April 1920, that he hadn’t been very optimistic as to his chances of success, notably because the issue had been raised in the press several times. Some curious suggestions, he reported, had been made:

‘there were some who suggested that the entire collection should be purchased by the Allied Governments and presented as a gift to the Belgian people, to compensate them for the monuments and art collections destroyed by the Germans.’

He thought that Portugal should be compensated in exchange for the antiquities and that £15,000 would be acceptable – a sum that could be realised by the sale of duplicates (FO 371/5186).

The India Office then called on a ‘Conference of the Departments interested in the possible recovery and disposal of the Mesopotamian antiquities now at Lisbon.’ Held on 10 May 1920 and gathering representatives of the India Office, the Foreign Office, the Treasury and the British Museum, the Conference agreed that:

‘it was clearly undesirable to offer a direct bribe to the Portuguese to induce them to give up articles which, although originally stolen by the Germans, have become to all intents and purposes a prize of war.’

At the same time, the Conference acknowledged it was unlikely the Portuguese would release the antiquities ‘without the prospect of a quid pro quo’. It was eventually suggested that in return for having preserved these antiquities, Mesopotamia should offer Portugal between £15,000 and £25,000 – a surprising sum to part with just after the war (T 161/5/6).

In November 1920, the Portuguese Government decided to keep the antiquities, which were presented to the University of Porto. The Foreign Office noted: ‘This appears to be that’ (FO 371/5186).

It wasn’t exactly true. The issue arose again in 1924, when Germany began negotiating the release of the antiquities to Berlin (FO 371/10118). Frustratingly, the relevant papers in Foreign Office Records, which I had found in the index, have not been preserved, but Walter Andrae wrote an account of the negotiations, published in April 1927 in the Bulletin of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. He recounts how, after several failed attempts, the Assur treasures were finally exchanged for objects ‘donated’ by all the departments of the Berlin Museum and travelled to Germany in the summer of 1926, arriving in Berlin on 2 September.

The Assur Treasures can still be admired today in the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, while the German ‘gifts’ to Portugal are housed by the Natural History Museum of the University of Porto. Perhaps it was, after all, ‘fair international reasoning’.

Of course it was not a dispute between “England” as stated at the beginning of the blog but one with Britain.

Hi David, thanks for reading the blog! The Museums involved in that dispute were the British Museum and the V&A – ‘museums in England’.

[…] ‘Fair international reasoning’ […]

Very interesting Julliete. I do hope you can come down to the Algarve and give a lecture!!

For a small country, Portugal has a fascinating history. And interesting that Gertrude Bell was involved–one of my heroines. Thanks for sharing this story.