Recent advancements in AI, improvements to collaboration platforms, and new tools for telling stories offer exciting opportunities for how researchers and the public understand and engage with the past. To explore some of these, The National Archives is hosting a collaborative digital hackathon, online and in-person, on 27 and 28 January 2025.

Read on to find out more about the real historical data we’ll be using – records from the world of early photography – as well as the problems we’ll be working on, and how you can participate.

The world of photography copyright

In the 1860s, photography as a medium and industry was coming under scrutiny due to its rapid development. Issues of ownership and copyright were becoming impossible to ignore, and so debates ensued around how photography should be defined and protected under the law. This culminated in the 1862 Fine Arts Copyright Act, which in turn required the registration of photographs, paintings and drawings with the Stationers’ Company, a system which continued for almost 50 years.

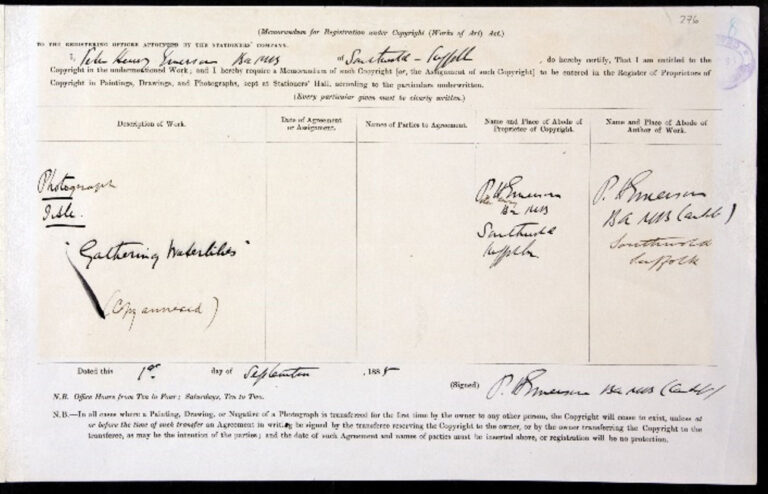

Those registering a work were instructed to enter a description of the work being registered, along with the name and place of abode of the copyright owner (or proprietor of copyright), and the name and place of abode of the copyright author (the artist or photographer). The forms were then dated and signed by the owner and in many cases a copy of the work (in the form of a print or sketch) was attached to the form.

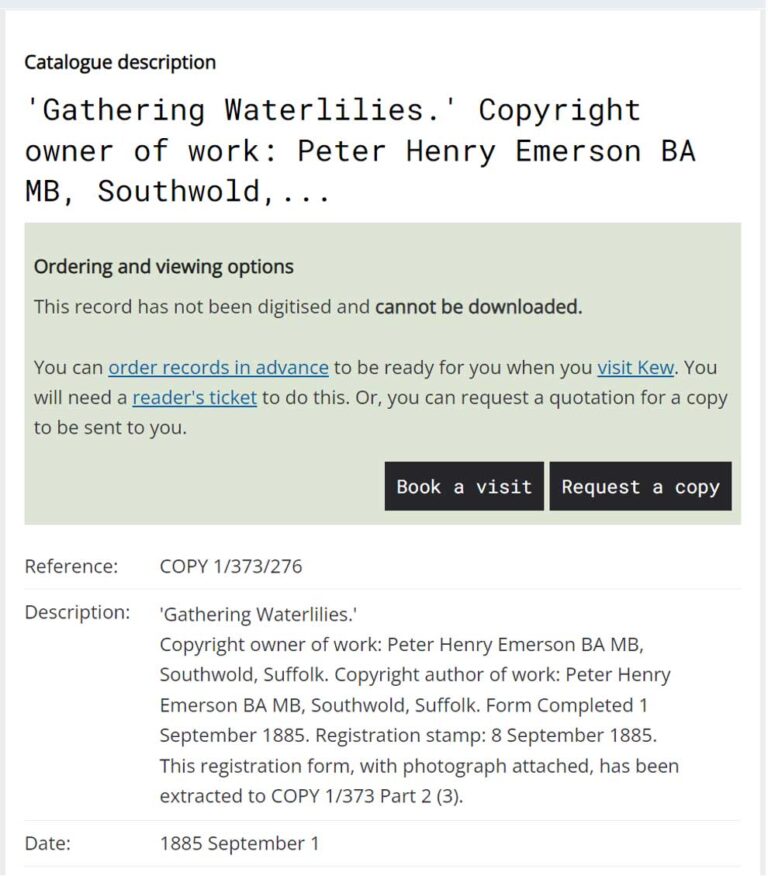

These registration forms and attached artwork, along with related registers and indexes, were eventually transferred to the Public Record Office, now The National Archives. This collection (COPY 1) comprises over 400,000 individual entry forms, and the entire photography collection (over 133,000 single items) has been fully catalogued thanks to the precious and invaluable work of volunteers. The metadata is openly available and downloadable from The National Archives’ online catalogue, Discovery.

The metadata includes each document classification and the full transcription of the description of the photograph, as well as the key stakeholders (copyright depositor and owner) and the location of the registration.

Making the data useable

The richness of this metadata can open exciting opportunities to research the world of early photography through digital methodologies, and to contribute to already-expanding research into the legal history of intellectual property, socio-cultural history and business history, to mention just a few. It has also the potential to open new interdisciplinary research avenues.

However, to do so, the data requires complex manipulation.

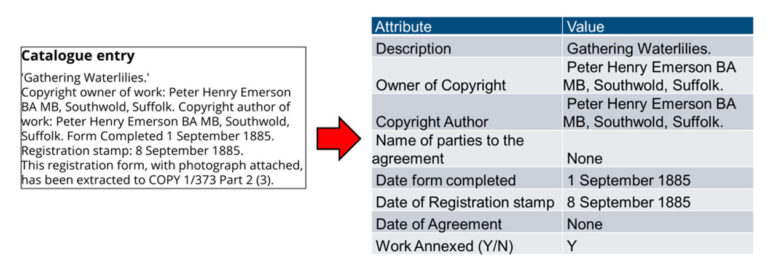

First, because it has to be ‘structured’ to be usable for analysis, because the content of the forms has been transcribed as free-form or semi-structured text to fit the catalogue’s requirements (eg all names, addresses and the description are one line of text).

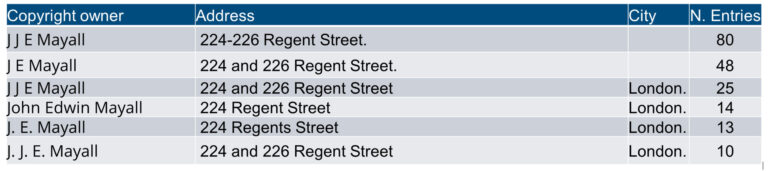

Second, because the original records have been transcribed faithfully as per archival practices, they reflect the many variations in spelling of names and/or places in the original records. While humans can see the variant spellings are likely to refer to the same things, computers need an exact mach. This means that to be able to connect records, the mentions of individual photographers, organisations and places in the descriptions need to be normalised and disambiguated (linked together even if they’ve been recorded differently).

This need for complex data cleaning creates problems for analysis, visualisation and digital storytelling. It also indicates that although precious data is available, it can be difficult to use to its full potential, limiting or excluding potential research opportunities.

Addressing the above has usually required either painstaking manual work or the application of programming skills. However, recent advancements in AI offer new methodologies and possibilities that help the transformation and cleaning of largely semi- and unstructured data. At the same time, hybrid collaboration platforms have become more robust, creating new opportunities to experiment with new forms of digital collaboration.

Collaborative digital hackathon

With all this in mind, we have decided to use the metadata of the collection of forms deposited to register copyright ownership of photographs between 1842 and 1912 (from COPY 1) to test data cleaning and processing methodologies, and to experiment with visualizations and interesting forms of storytelling related to the world of early photography. In addition to this direct research contribution, we will investigate the benefits and constraints of running a hackathon.

We want to bring new perspectives to exploring archival collections through metadata by experimenting collaboratively with tools such as AI, but also network analysis, entity extraction, disambiguation, and visualisations. During the hackathon we will encourage collaboration between teams onsite and online, each working on different parts of the problem but sharing data, tools and ideas.

If you have experience with coding, and are interested in digital humanities, computational linguistics, software development, digital research, and if you are interested in working with data exploring the history of intellectual property and early photography, you can now sign up to attend the digital hackathon.

To find out more and express your interest in attending, either online or in-person, please apply to participate.