This blog is the culmination of a number of years of work which started with a pilot workshop at Stillpoint Spaces London in June 2019, when a diverse group of people from different personal and professional backgrounds came together to look at the themes of race and racism. As part of the day, participants broke up into smaller groups. One of the sub-groups looked at how archives, education and engagement could address the themes of the day.

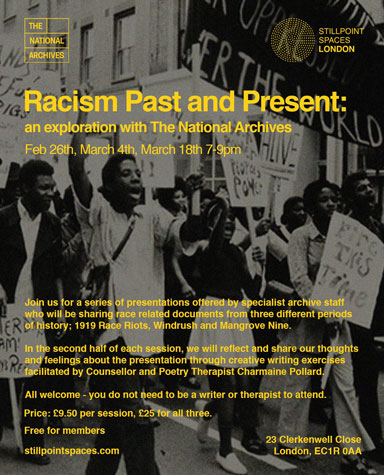

In response to this day, The National Archives developed a programme of workshops under the heading of ‘Racism Past and Present’, in collaboration with Stillpoint and the counsellor and poetry therapist Charmaine Pollard. One of the aims of the workshop series was to offer to tell the long story of the Black community in Britain from the end of the First World War though to the early 1970s.

For all of us on the project, this went to the heart of exploring race and racism: the need to take into account this wider arc of history, for example from colonial subject to British citizen, so that in talking about more contemporary events we would have a grounding not only in the immediate past but could look further back.

Now with increasing interest in what we have been doing, I, Iqbal Singh, hope that this blog can assist people in understanding what we have found out so far, and how we are planning to take matters forward. Here I will interview Professor Kevin Lu, University of Essex, and Dr Aaron Balick, Psychotherapist and Director of Stillpoint, about how our pioneering collaborations are now developing new methodologies that are scalable, based on their analysis of a collaborative workshop in March 2022 and the publication of a report that you can download here.

The highlights include:

Firstly, there is a need to integrate the presentation of archival research with quality psychological interventions that enable a personal relationship with that material. But, to be clear, this will not be group therapy.

Secondly, this requires psychologically safe environments so participants can share the impact that these records have on them, while learning from others’ experiences from different ethnic backgrounds.

Finally, it is essential to involve participants in the co-creation of something as a part of this process. For example, a light psychological intervention such as creative writing, based on themes in the material, which enables participants to process that material more holistically.

Iqbal, can you tell us more about this pioneering initiative?

As someone who works in a public engagement role, I am regularly introducing people into the archives, and devising projects working with archival records. Arriving at The National Archives in 2015 in anticipation of the 70th anniversary of the Partition of British India, and seeing for the first time records describing the extraordinary violence, I began involuntarily crying. I asked myself many questions including: was it my unique background, the only child of a Sikh mother and a Muslim father whose lives were so closely associated with the Panjab where the vast bulk of the violence and displacement took place that was the trigger? I was taken aback by what I was experiencing, finding myself choking up in front of visitors and unable to speak, or to hold back what felt like an ocean of tears.

I am aware that opinion is divided between those who want to hear about feelings in the archives and those who don’t, but what has become undeniable for me is that archival records can evoke emotions. This is informing my approach as I now mature into my role and employ the methodologies of a historian, dissecting the records and the projects I lead by asking deeper and richer questions and admitting more complexity in to my analysis.

Alongside the historical questions that fascinate me, the questions about why people feel the way they do when looking at archives, or talking about these histories, remains pressing. Is there some inter-generational trauma? Or is it a question of age? Would I have reacted to the archives in the way I did as a twenty-year-old in the same way as I reacted to them as someone in their early fifties?

In that sense, as I have said before, we are involved in a dual process of both dissecting the record but also attuning ourselves to those viewing the record or sharing it with others. Doing so affords opportunities to invite discussions that engage participants not only in discussions about records and histories, but also about feelings and emotions.

It was on the back of my early encounters with the archives that I went about setting up a collaboration between The National Archives and psychotherapists at Stillpoint Spaces and the Black, African and Asian Therapy Network (BAATN). This was aimed at kick-starting these important conversations as well as psychological processing of challenging material relating both to 20th-century Black British history and Indian indentured history. I was interested in the ways in which these emotive and complex histories could be approached using a format that allowed participants to encounter the fruits of archival research and then work in a therapeutic way to address what the re-telling of these histories brought up for the participants. In designing content and spaces that allowed the processing of emotions, new methodologies – including arts- and practice-based approaches – emerged to engage audiences as co-researchers.

The aim is neither to sensationalise nor sanitise but to face up to the archives in a way we have to face up to so many other things. There is, therefore, an importance for me as a historian of taking the long view, inviting more complexity/ambiguity/paradox into my analysis of the past, for example, by drawing on different and competing perspectives.

A short reflection on my father recently passing away, and the emotional processing this entailed, reaffirms a call for more honest conversations with ourselves and with the archives. It also provides a unique opportunity to get in closer contact with the body and what can feel more ‘natural’: to be upset, to cry, and to want to talk/paint/write etc. While I would not want to equate the passing of an elderly parent or guardian with encountering an archival record, there is still something for me that is similar. I was not aware when my father would pass away; I knew it was something I would confront at some point, and for me the Partition story had a similar knowing: I knew there was no way I could avoid encountering it again. In grieving for my father, I had to invite in a lot more questions about his life and to allow myself space to physically grieve also.

Aaron, can you introduce us to the report you and Kevin have written on developing new methodologies?

Our aim in putting on the event in March 2022 was to apply what we had learned in our previous collaborations into a workshop that we could ‘road test’ with the input of several participants who would also act as co-researchers. We wanted the event to stand alone as a nourishing experience while at the same time subjecting it to a qualitative evaluation in order to develop a replicable learning methodology from it. To this end we invited a small group of participants that were known to us with the understanding that they would participate and feed back about the process.

The half-day workshop began with lunch with the intention of creating a shared intimate and informal space. Participants were reminded about the purpose of the workshop and were aware that it was being observed and recorded for research purposes. Two presentations were offered by records specialists from The National Archives, Vicky Iglikowski-Broad and Kevin Searle, followed by an opportunity to ask questions about the details of the archival records.

After this, the psychological and emotional components were brought into frame through the facilitation of a poetry therapist, Charmaine Pollard, who gave the participants writing prompts that encouraged a deeper engagement with the material, which was discussed in pairs, and then the larger group. The last hour was spent reflecting on the process itself, identifying what was helpful or a hindrance to our proposed integrated learning process. Our observations and recordings were subjected to a thematic analysis and written up in the report which can be used as a tool to develop this methodology further.

It was also proposed that any themes, productions, and outcomes could ultimately be fed back into some kind of archive of its own – such as a book or website.

Kevin, can you explain more about the report and its headline findings?

A preliminary analysis of the data gave rise to 6 overarching themes and several sub themes. The six major themes were: vulnerability and resistance; resilience; democratisation; embodiment; ancestry and family; and nostalgic disorientation. As the session progressed, it became clear that all participants were working in a liminal space and choosing to work within, and occupy, that very third space, i.e., the space between the individual and the social/collective; between individual memory and collective memory. This is perhaps a major reason why individual associations and memories were used as a way into, and to reflect upon, the archival materials. Not only were co-researchers describing the emotions that arose, they were using their own experiences as reference points that interweaved and created points of connection with the sources.

Acknowledging and honouring our subjectivity actually paves the way for a more nuanced and attuned engagement with primary sources. Having purposely created this space for reflection and making this known to co-researchers from the outset, my sense is that the group was more attuned and responsive to the presentations delivered by our archive specialists. Noting one’s subjectivity also allows one to be more mindful of the ways in which history encompasses us all; we do not live in isolation, and an understanding of our individual psychologies is incomplete without acknowledging the historical resonances and unresolved complexes that shape who we are.

Kevin, can you say more about the intersection between history, psychoanalysis and art?

Working in a multidisciplinary manner, we are taking the best from the growing field of psychoanalytic approaches to practice as research and turning our attention to history and the social, i.e., acknowledging that who we are and what we become cannot be divorced from the collectives we inhabit and to which we contribute. Individual development and greater awareness of who we are is both relational and historical, and a more holistic approach to understanding both subjectivity and history requires a dialogue and holding a space of delicate tension in which new knowledge may arise.

History as a discipline is suffering; student intakes across universities are in decline and established departments of excellence are under attack. We need to address this and hold up a mirror to ourselves: why is this happening? One way to begin this important work is to open up and develop the ways in which history already includes the ‘I’; it can be a discipline that works psycho-socially, one that embraces subjectivity, maintains a deep respect for the past and the historical record, while creating new avenues to embed a serious study of emotions that intersects with, and becomes the bridge between, psychology and history.

The past can be traumatic, for individuals, collectives, nations, etc. Many have written on this, including Robert Jay Lifton, Vamik Volkan and Karl Figlio. We cannot understand the intricate relationship between history and memory if we do not allow room for, or have a framework to understand, the myriad of ways in which emotions are also ‘stored’, archived and embedded in the past, waiting for us to rediscover them, work with them, and ultimately, work through them.

Our method is aiming to facilitate this by providing an arts-based approach to encourage and create a space for the expression of these very emotions. In our pilot session, we utilised poetry; in future, we could be mobilising the creation of images, thereby generating our own group memory and artefacts to encapsulate moments of recognition and, potentially, reparation. Images may also capture the intricate transference/countertransference relationships in such engagements – not only transferences circulating within the group, but our transference/countertransference reactions to the archival materials themselves.

Aaron, where do you see this development going?

The experience of running the workshop was positively received and nourishing to all who attended. We feel that the feedback and further development through incorporating the feedback and the findings from the thematic analysis provides a clear roadmap for replicating these groups around a variety of themes via the use of archival material. Due to the sensitive emotional material that such workshops may provoke (and are intended to provoke, safely), much thought and care would be required in running further workshops based on this methodology.

A basic framework of these workshops would require:

• An individual with experience facilitating groups where emotional material is discussed and worked through (a mental health professional), and this person should be trained up in the proposed methodology.

• A second person proficient in the therapeutic use of their medium (whether that be writing, drawing, painting, dance, etc.) as this is an arts-based practice.

• A records specialist to deliver the presentation based on the specialist theme.

• An observer/researcher to be present to collect themes and materials to be fed back into a final production (e.g. an anthology, art installation, or website).

Iqbal, do you have any concluding thoughts?

In rolling out this collaborative practice, we are sensitive to the past but also clear that this is facing up to pasts means we cannot hide anything. We need to see the pasts for what they may have been and allow interrogation. In my experience, what may appear the most innocuous of documents or references relating to past tragedies or injustices can also be a trigger, and therefore there is no foolproof way of protecting us. It makes more sense to prepare individuals to face these histories. Often, we find that the stories are never straightforward and that if we invite nuance into our arguments and approaches, then matters are also never quite black and white.

The archives are not detached from our emotions and in that sense, they are about both facts and feelings. It’s our ability to be aware of this mix that, going forward, is so important to me. The projects I have led are practice based, interdisciplinary and now very much located at the heart of our role as a public facing archive. As we delve deeper into questions about how we as individuals experience the archive and how we relay these stories to one another, emotions will continue to play a central role: not only our own emotions but also those of the subjects we study.

References

Ancelin Schützenberger, A. (1998). The Ancestor Syndrome: transgenerational psychotherapy and the hidden links in the family tree. London: Routledge.

Figlio, K. (2017). Remembering as Reparation: Psychoanalysis and historical memory. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Langer, W. L. (1958). ‘The Next Assignment.’ American Imago, 15(3), pp. 235-66.

Lifton, R. J. (1985). Home from the War: Learning from Vietnam Veterans. New York: Basic Books.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma. London: Penguin.

Volkan, V. (1998). Blood lines: from ethnic pride to ethnic terrorism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.