Content note: This blog post contains details of the maltreatment of enslaved people in the 19th century.

This blog is the result of a three-month placement I undertook at The National Archives in 2021 during my PhD at King’s College London. While here, The National Archives invited me to help them better understand the content and structure of the records of the Foreign Office’s ‘Slave Trade Department’.

What are the records of the Foreign Office’s ‘Slave Trade Department’?

Under the Slave Trade Act of 1807 the, ‘Purchase, Sale, Barter or Transfer of Slaves… in, at, to or from any Part of the Coast or Countries of Africa’ was ‘abolished, prohibited and declared unlawful’. Although practices of slavery continued in the British Empire after 1807 in a variety of ways, over the following decades the British government invested increasingly heavily in suppressing the enslavement of Africans for sale overseas.

Between 1841 and 1882 the ‘Slave Trade Department’ of the Foreign Office had responsibility for some of this work. The department was responsible for international treaties against slavery, and for agreements with foreign powers to seize the ships of those engaged in the trading of enslaved people.

Much of the correspondence of the department was with the ‘Slave Trade Commissioners’. The Commissioners worked with representatives from other countries to adjudicate cases relating to seized ships; dividing the profits from selling the ships and their goods, and liberating the enslaved. These ‘Mixed Commission Courts’ were held in Africa, North, South and Central America, and the Caribbean.

My research focussed on the records relating to slavery in the Indian Ocean in the second half of the 19th century. Across two blogs I’ll describe some of the findings. First, I’ll look at what the series can tell us about the experiences of the enslaved; in a second blog I’ll explore the role slavery played in regional diplomacy.

What the correspondence reveals

FO 84 and FO 881 series records are composed of the correspondence with officers of the ‘Slave Trade Department’ in the latter half of the 19th century, a time when the efforts of the British Government to suppress the trade in enslaved people were being concentrated more on the Indian Ocean.

These records reveal a variety of important information, from quantitative statistical data regarding the extent and geography of the traffic, to qualitative first-hand accounts of the experiences and conditions of those who were enslaved. These include harrowing tales of the escape and capture of the enslaved, dramatic reports of their liberation and manumission, and descriptions of the changes in the tactics mobilised by the British Navy and Foreign Office against the traders of enslaved people.

An account from an unnamed ‘sepoy’

Some of the most important records in FO 84 capture eye-witness accounts of the experiences of the enslaved. One of these comes from an unnamed ‘sepoy’ (a low-ranking Indian infantryman in service of the British military) who accompanied traders of enslaved people on their way to the East African coast, noting that ‘they were able to tell us at what cost of human suffering, at what price of crime, the domestic institution of slavery at Zanzibar is sustained’: how and where the enslaved slept, what and when they were fed, how and where they were transported, and how and for what reasons they were tortured as punishment or killed. The ‘sepoy’ concludes:

‘if we ponder upon the matter, if we allow our minds to dwell upon the accumulation of horrors that are begotten of the enslavement of the twenty or thirty-thousand Africans who yearly do reach the coast alive, is it possible to recognise any political necessity so great, any commercial interests so valuable, any rights… to enslave the African so absolute, any hope of ulterior good to Africa from the continuance of this sin-encompassed traffic so well-founded, as to justify its tolerance by a… nation which has the power wholly to prevent it?’

The unnamed ‘sepoy’. Catalogue ref: FO 84/1279, 154-158.

A boy’s liberation

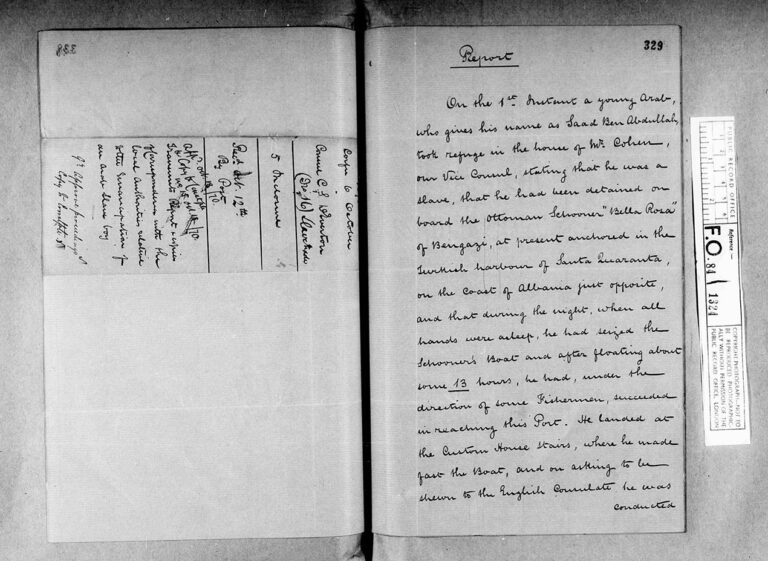

Another account describes the liberation of an enslaved boy named Saad Bin Abdullah who was detained aboard an Ottoman schooner. He escaped on a long boat in the middle of the night and reached Corfu after thirteen hours of constant rowing. He ran straight to the English consulate, where he was escorted to the home of the consul. Ottoman officials tried and failed to arrest the ‘fugitive’ but domestic staff in the Consul’s home barricaded the building. The Ottoman group tried to suggest he was not enslaved, demanding evidence of his slavery, but failed to prove their claim that he was a sailor.

Subsequent letters detail the medical and legal examination that Bin Abdullah underwent before being furnished with manumission papers, after which he was recaptured and then re-released by Greek police (catalogue ref: FO 84/1324, ff. 319-344).

‘overjoyed at their release’

In a third account, a man called Vernon Lushington encloses for the Foreign Secretary, Lord Clarendon, letters from the Commissioner, Dr. Kantzow, vividly detailing the dramatic capture of a dhow (a vessel characteristic of the Arabian Sea) by the British military which resulted in the liberation of two hundred and thirty-six enslaved people from so-called ‘forty Arab’ traders. Lushington describes ‘a volley of musketry from the beach. … The slaves on the other hand were healthy and in good condition, and overjoyed at their release’ (catalogue ref: FO 881/1703, 3).

Several pieces of correspondence describe the process by which rescued enslaved people in Egypt had to prove ‘their right to freedom’ before an assembly of local elders. One part of these proceedings was that if any man stated that he had taken an enslaved person as his lover, then those women were considered the legal wives of their masters (catalogue ref: FO 84/1324, 345-466).

The task of attempting to hear the voices of enslaved people who were denied access to the means of self-expression or were so dehumanised as to have their voices rejected and unrecorded is a difficult but important one. Most of the correspondence contained within these records pertains to diplomatic and military matters but occasionally such stories emerge, which begin to offer more insights into the lives of the enslaved, even if it is just a name, an age, a location, or the story of their escape, their liberation, their capture, their recapture, or even their freedom.

We need to be conscious that these stories are mediated by the diplomats or military men who recorded them, and aware of the power dynamics which characterise the narratives. Nevertheless, such rare literary artefacts still offer us opportunities to recover what we can of the experiences of those who were suppressed, ignored, and maltreated.

Rhys Sparey is a PhD student from King’s College London, who spent three months working with The National Archives on a placement in 2021 funded by the London Arts and Humanities Partnership.