The counter-intuitive thing about being trapped in an embassy is that everyone involved always wants to get you out.

In the case of Julian Assange, rooming in Knightsbridge since June 2012, both the Ecuadorian and British governments have batted various schemes around to secure his exit. That August, William Hague warned of the Diplomatic and Consular Premises Act, which seemed to allow a Foreign Secretary to withdraw ‘consent’ from an embassy, stopping it, in effect, from being an embassy. It subsequently emerged that the Ecuadorians too were considering schemes to facilitate Assange’s departure, which included putting him inside a diplomatic bag, using ‘fancy dress’, a Bond-esque run across rooftops ‘towards a nearby helipad’ or via a trip to Harrods, where, it was presumably assumed, getting lost was virtually guaranteed.

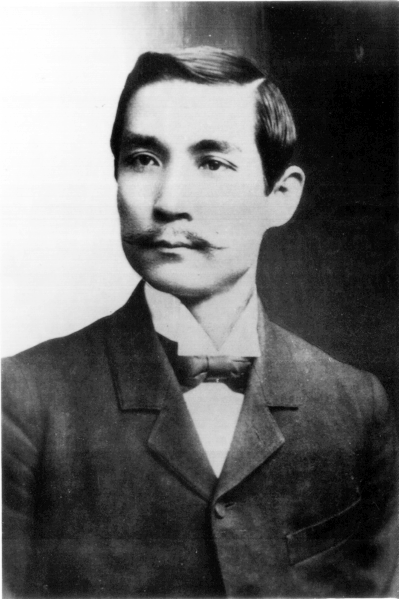

Sun Yat Sen, August 1900 (source: Wikimedia Commons)

The problem of extracting someone from a London embassy is a relatively unusual one, but not unique. In October 1896, Sun Yat Sen, the future revolutionary founder of modern China, was visiting his old friend and medical school teacher Dr James Cantlie in London. Sun was wanted by the Chinese authorities for attempting to organise an uprising in Canton (Guangzhou) against the Qing government the previous year; a number of his co-revolutionists were arrested or killed but Sun escaped, travelling to America and then on to Britain.

Sun claimed afterwards to the Metropolitan Police that his reason for visiting London was ‘with the view to continue my studies as Doctor of Medicine’. We can safely discount this; Marie-Claire Bergère, Sun’s modern biographer calls him a ‘professional conspirator’ in this period.

He spent much of his time in London at Cantlie’s house on Devonshire Street. Only around the corner was the Chinese Legation on Portland Place. Sun again rather unconvincingly told police he had no idea where the embassy was located. But in his published account of what followed, he recounts the doctor’s wife Mabel joking that he should avoid the building or ‘they’ll catch you and ship you off to China’. ‘We all enjoyed’, wrote Sen, ‘a good laugh over the remark’. He was not, unfortunately, laughing for very long.

Walking in Portland Place on Sunday 11 October, Sun, by his own account, fell into conversation with a Cantonese stranger who steered him, apparently unknowingly, towards the embassy. On arrival there two men came out and hustled him over the threshold. He was taken to a third floor room and there encountered the formidably bewhiskered figure of Sir Halliday Macartney, Secretary to his Excellency, the Ambassador.

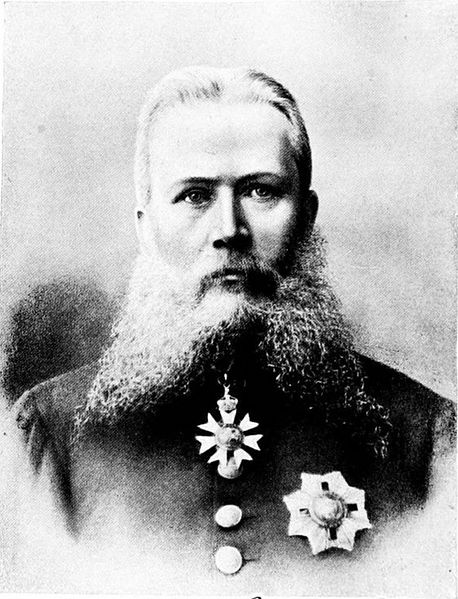

Sir Halliday Macartney (source: Wikimedia Commons)

‘He said’, recalled Sun, ‘you are in China now, here is China’. When Macartney left, the door was locked and guards were placed outside. Subsequent witnesses within the embassy claimed staff had already tested a number of rooms and rejected those whose position allowed easy exit out of the window.

Macartney told Sun that he was acting on instructions from the Chinese Ambassador to the United States and that he needed to contact the Zongli Yamen (effectively a Chinese Council on Foreign Affairs) for clarification before he could permit Sun’s release. It was Mr Tang, the embassy’s interpreter and one of the men who had brought Sun into the embassy, who informed him of the reality of his situation: he would be taken to China.

‘I asked how I was to be taken from England and Tang said a ship had been chartered to take me to China and probably it would be one of the Glen Line Steamers… I said if I am to be taken away I must go outside this place through the streets and I can call for help. He replied you will [be] tied up and your mouth gagged put in a box or bag and taken on board of ship at night.’

This (and the rumour among the embassy’s staff and servants that Sun was a dangerous lunatic) constituted the plan to achieve his extraction from the capital. This plan failed. Glen Line informed Macartney that the vessel intended to transport Sun had been delayed and would not be available until mid-November. In addition, Sun began to attempt to smuggle notes out of the building, despite limited access to paper and ink, first by throwing them out of the window and then, after it was nailed shut, by way of the embassy servants. They proved reluctant to assist: the embassy’s porter George Cole accepted Sun’s notes and then passed them to Macartney. It was the embassy’s housekeeper, Mrs Hoyle, who likely met Sun only once, who had a note taken to Dr Cantlie’s house.

Extraordinarily, the original handwritten note delivered to Cantlie survives in the Home Office file. ‘It is a very sad case unless something is done at once for the poor fellar he will be hung as sure as he goes to china. I hope you will do your best at once. Dont take no excuses at the door he is here. You have got the truth.’

![Mrs Hoyle[?]’s letter (catalogue reference: HO 144/935/A58272)](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/01160303/HO144-935-A58272i.jpg)

Mrs Hoyle[?]’s letter (catalogue reference: HO 144/935/A58272)

Emboldened by Mrs Hoyle’s example, Cole now took a note from Sun to Cantlie. The British authorities now knew of Sun’s imprisonment. Cantlie failed to obtain a writ of habeas corpus at the Old Bailey but Foreign Secretary Lord Salisbury denounced Sun’s imprisonment as ‘an abuse of the diplomatic privilege’. Macartney played for time and denied that Sun had been induced into the embassy ‘by guile’ but his visits to the Foreign Office were accompanied by a further assault on his plan: silky threats from British officials. There was a story ‘provisionally’ on hold with the Times, did he want a great scandal? It was also pointed out that as a British subject his own diplomatic status could be withdrawn – in other words he could be arrested.

Macartney released Sun. On his release, wrote the Standard, ‘the official of Scotland-yard undoubtedly gave sound advice when they counselled him to have nothing more to do with revolutions.’ History amply records that Sun Yat Sen did not consider this advice to be sound.

Sun believed George Cole to have been instrumental in his release, and Foreign Office and Metropolitan Police files reveal that he supported Cole and later his widow. But behind every recalcitrant and rather feeble man is a great woman: it was Mrs Hoyle, whose testimony does not survive as she was not interviewed by the police, who seems to have instrumental in revealing Sun’s situation to the world.

For the Times, the incident showed that an embassy was not inviolable after ‘courteous notice’ and it went on with great prescience ‘there is also an agreement that, except possibly in Spain and in the South American Republics, the [embassy] is no longer an asylum for even political offenders.’

Today, Julian Assange does not need to pass notes to put across his message and his situation bears interesting but only very superficial comparison with that of Sun. But the essential problem remains the same: embassy staff, UK government and the man himself are united in wishing him outside the embassy, but with very different visions of how that exit should be effected.

The problem it turns out is not how to escape from an embassy but how to escape the consequences of what caused you to go inside.

[…] The counter-intuitive thing about being trapped in an embassy is that everyone involved always wants to get you out. In the case of Julian Assange, rooming in Knightsbridge since June… Go to Source […]

Very interesting! Except the Buzzfeed link about the “escape plans” is rubbish; the Ecuadorians were merely noting the over-excited ruminations of the British press at the time Assange first went into the embassy:

http://www.theguardian.com/media/2012/jun/21/julian-assange-escape-routes-ecuador-embassy

http://www.theguardian.com/media/2012/aug/16/julian-assange-ecuador-embassy-wikileaks

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2193217/Arrest-Assange-circumstances-Police-gaffe-secret-document-reveals-WikiLeaks-founder-dealt-tries-leave-embassy.html

But you’re right about the real problem being “how to escape the consequences of what caused you to go inside”. Look’s like the USA wants to put him in jail for 45 years if these US warrants listing his alleged “espionage” offences are anything to go by:

https://wikileaks.org/google-warrant/press.html