Having located a map on a desk of a house in Dieppe, northern France, which showed the English Channel, the coast of France and the south coast of England, Privates Neil Campbell and Hugh Oliver, taking their course from the stars, set off towards home.

Halfway across the Channel, they came across the minesweeper Dalmatia, which they were permitted to board at 19:00. After remaining on board for two nights and a day, as the trawler was engaged in minesweeping operations, they arrived in Portsmouth on Sunday 7 July 1940. The account of their escape is one of a number of those detailed by those who succeeded in their attempts, and are available in the collections of The National Archives.

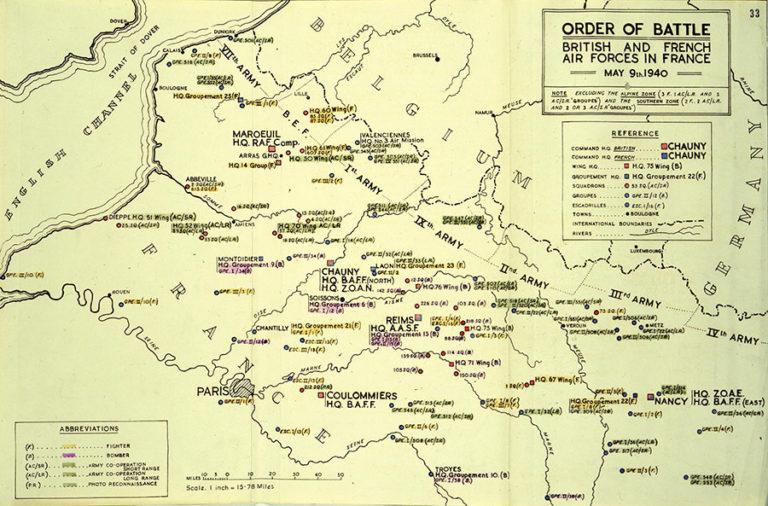

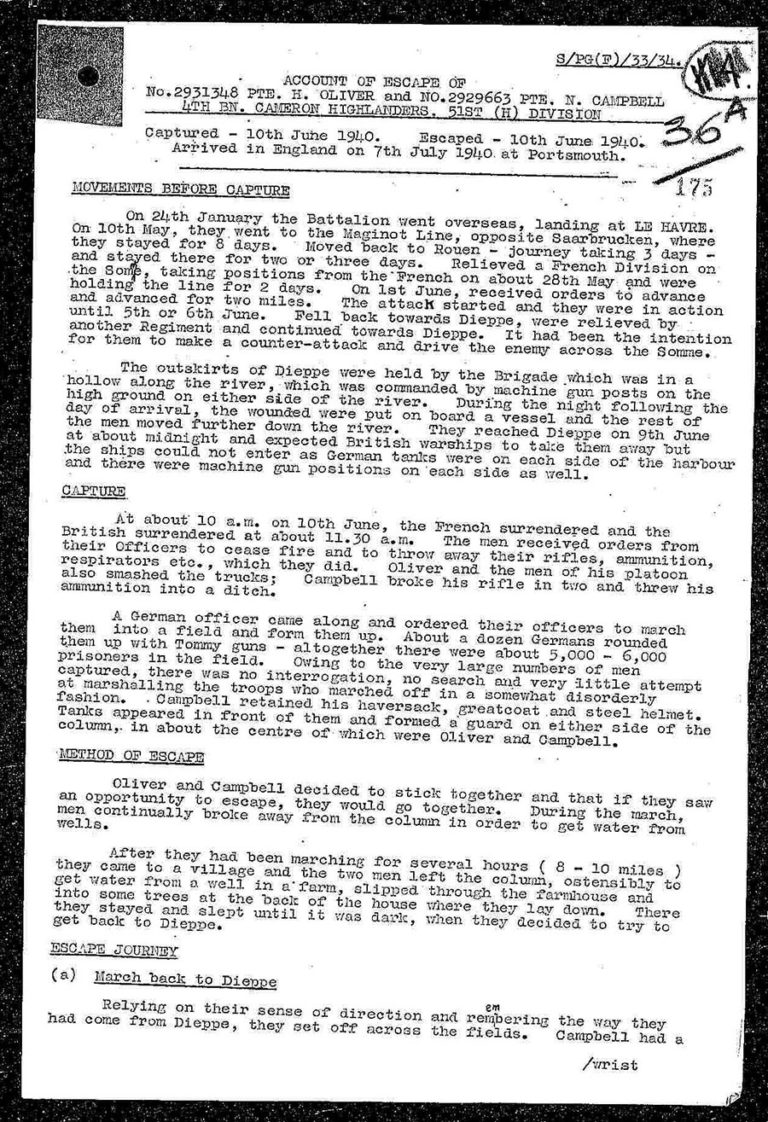

Both Campbell and Oliver had been members of 4th Battalion, Cameron Highlanders, 51st (Highland) Division, and were captured on 12 June 1940 when the entire Division surrendered as it attempted to reach Le Havre in Normandy. Its surrender effectively ended British resistance on the French mainland.

Campbell and Oliver had been in France since January 1940, had taken part in various attacks in the lead up to the evacuation of Dunkirk, and were expecting to be taken away by British warships at Dieppe. They were prevented from evacuating because German tanks had taken up positions at the harbour so that ships could not enter, and their account can be found in WO 373/60/310.

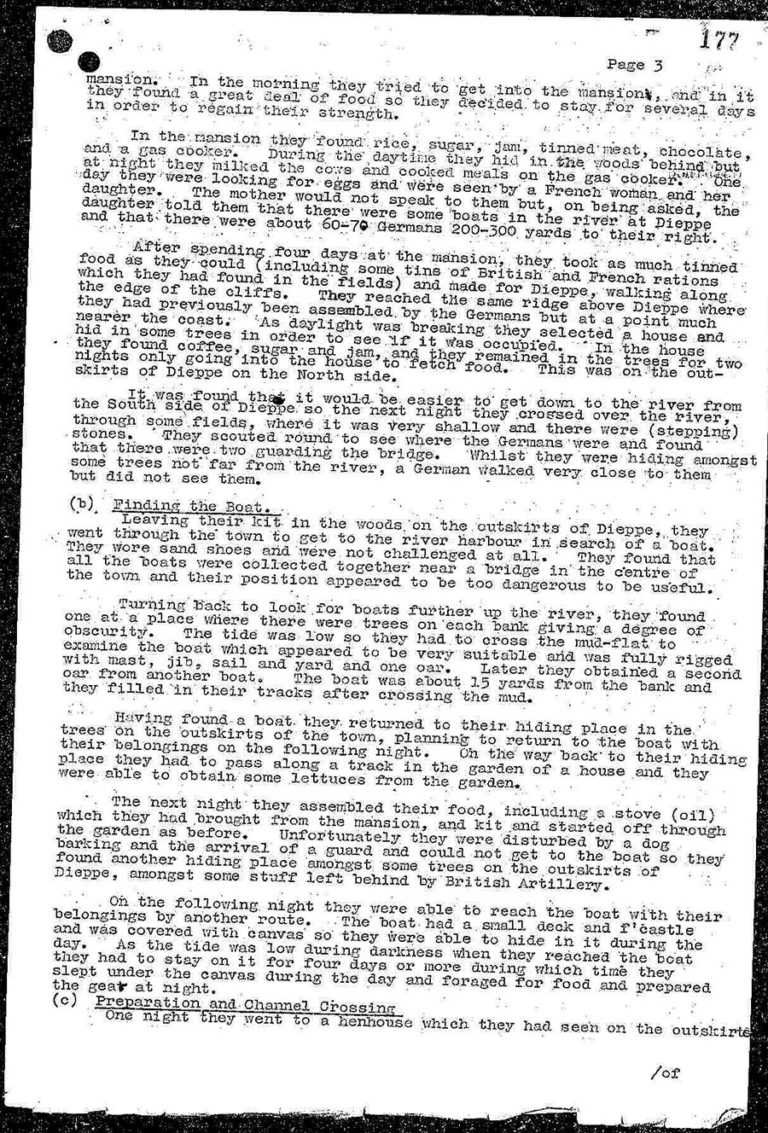

After being forced to march for several hours by their captors, the pair made a break for it, slipping through a farmhouse and into some trees where they sheltered until it was dark. Having decided to attempt to make it back to Dieppe, for several nights they proceeded across fields, progressing about one mile a night, making many detours along the way.

Eventually reaching a village north of Dieppe, they found a house, located 100 yards away from the German headquarters, while looking for food and water, and had to hide under beds in the attic when German soldiers entered to sleep. They themselves had slept in the house during the previous night and left as quickly as was permitted once the German soldiers had awoken.

This was followed by many other close encounters with German soldiers, as they made their way along the coast, where they eventually found a boat. They proceeded down a river towards the Channel, using oars to fight against the wind, which was not in their favour. Eventually reaching a harbour where there was a lighthouse, they were spotted and fired upon by machine guns, but succeeded in getting away once they had managed to put the sail up on the boat, before they were picked up by the Dalmatia and sent home.

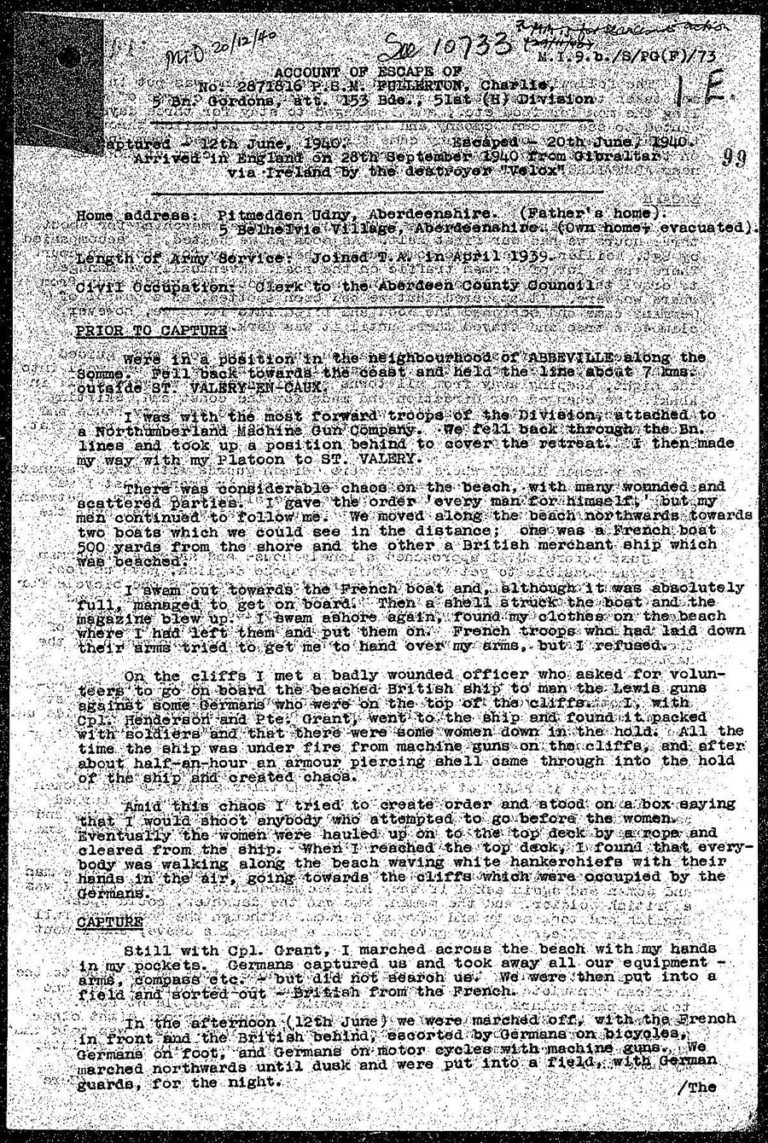

Platoon Sergeant Major Charlie Fullerton of the 5th Battalion, Gordon Highlanders, also recounted his experience of escape when he eventually reached Londonderry on the destroyer Velox on 27 September 1940, having spent more than three months making his way through France and Spain before leaving the continent from Gibraltar. The full account of his escape can be found in WO 373/60/290.

Prior to his capture on 12 June, Fullerton had even managed to board a French boat bound for England, before it was struck by a shell and its magazine blew up. After swimming back ashore, he helped a group of women, who were in the hold of a beached British merchant vessel which had just been struck by an armour-piercing shell.

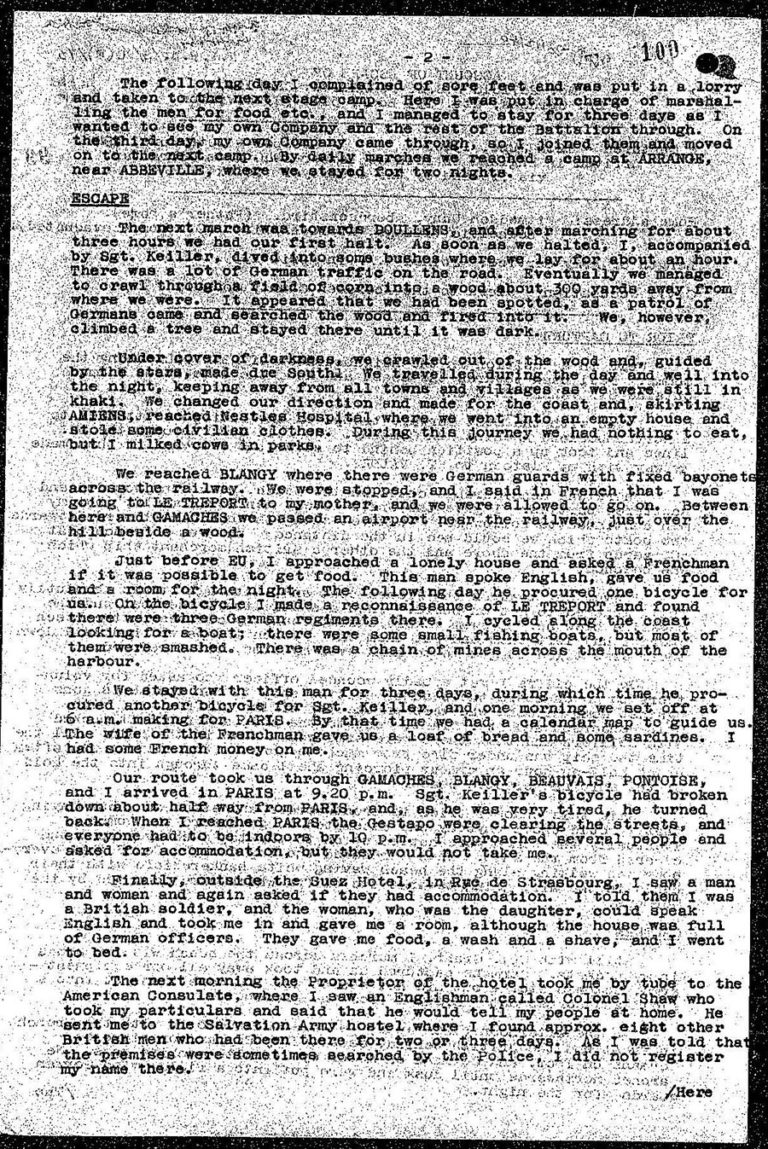

Once captured, and in a similar situation to Privates Campbell and Oliver, Fullerton and a colleague managed to leave their marching column by hiding in some bushes at the side of a road, before crawling into nearby woods under the cover of darkness. On discovering a house, the two soldiers stole some civilian clothing and were even stopped by German guards but were permitted to proceed by speaking in French to them.

Fullerton eventually reached Paris, with the help of French civilians and without his companion, where he found the Gestapo clearing the streets. After finding shelter in sympathetic households, he made his decision to travel to Spain.

He managed to travel southwards by train when he and two other British soldiers began their walk over the Pyrenees, taking a path which had been used by refugees during the Spanish Civil War. Over the border, they were met by Spanish soldiers and taken to a civil prison, before being moved to a camp, where they stayed for five weeks.

From here, they were taken to a prisoner of war camp, where they were made to work carrying stones, lashed by the guards if they fell behind, and had their heads shaved. Eventually a British representative arrived, with a note for the release of 15 of the British party. Fullerton was given food and railway tickets, and travelled to Madrid. Here, in the charge of the naval attaché, they made their way to Gibraltar and to freedom.

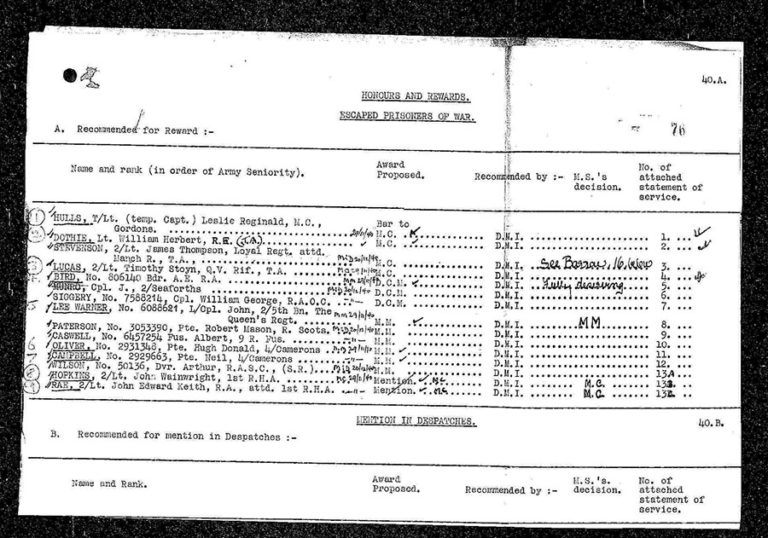

For their efforts, the three involved here were awarded gallantry medals. Sergeant Major Fullerton, for his performance ‘exemplifying courage, resource and determination of a high order’, and Privates Campbell and Oliver were all awarded the Military Medal. These recommendations, as well as thousands of others, can be found in the WO 373 series, which includes records for recommendations for Honours and Awards for Gallant and Distinguished Service, the majority of which have been digitised and can be downloaded from our website.

Having dipped into escapee reports (mainly RAF aircrew) and those of liberated POWs at Kew I am always humbled by the courage, ingenuity and compassion shown by those evading the German authorities.

This last quality is often extended by civilians in the enemy’s homeland – the very people who having endured Allied air raids might have been expected to be hostile.

Yet again another informative post. Thank you again.