As a French historian working at The National Archives, I am particularly interested in the Entente Cordiale. As an archaeologist, I am particularly sensitive to its egyptological side. My colleague James Cronan mentioned, a few months ago, the third paragraph of Article 1 of the Entente, which says: ‘It is agreed that the post of Director-General of Antiquities in Egypt shall continue, as in the past, to be entrusted to a French savant’. There is a bit more to the story, and the Entente wasn’t that cordiale when it came to Egyptology: nine months after it was signed, a party of drunken Frenchmen tried to force their way into an ancient site, and the British Egyptologist supervising archaeological matters in Lower Egypt was exiled to some unsavoury city in the Delta of the Nile.

The first report written by Lord Cromer, the British Agent and Consul-General in Egypt, regarding what the British could afford to give France in Egypt against the assurance that the French ‘would not obstruct the action of Great Britain in that country’, didn’t mention Egyptology. It seems that, in the first three months of the negotiations, no-one thought of it at all. In December 1903, however, Théophile Delcassé, the French Foreign Minister, asked Paul Cambon, the French Ambassador in London, to raise the issue of the French civil servants in Egypt. Cromer thought the British government could ‘afford to be very generous’ on that particular point, but it was more about granting them financial compensation for the loss of their jobs than about preserving them.

Lord Lansdowne (Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs) to Sir Edmund Monson (British Ambassador to Paris), 11 December, 1903. Catalogue reference: FO 881/8380

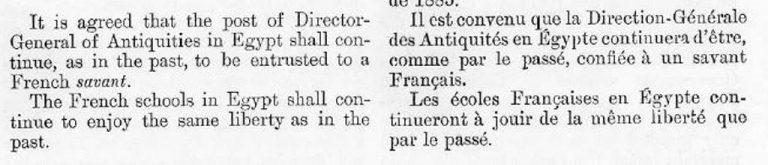

From then on, Paul Cambon tried to keep at least one Department under French control: the Antiquities Department, in charge of everything archaeological in the country and traditionally headed by a Frenchman. This was probably prompted by the everlasting French fear of seeing the British get their hands on Egyptian archaeology. Cambon made it quite clear that it would have been pointless to go to the French parliament with an agreement including the suppression of direct French control over the Antiquities Department. When the Declaration on Egypt and Morocco was first drafted in March 1904, the Antiquities Department was included in the very first article. Thus, due to a century of French presence on the banks of the Nile, Egyptology was taken into account in one of the 20th century’s most important diplomatic agreements. It is likely that this was done to appease French public opinion, still largely Anglophobe and very sensitive to the names of Auguste Mariette, the first Director of the Antiquities Department, and Jean-François Champollion, who had cracked the hieroglyphic system.

Surprisingly enough, the French newspapers hardly mentioned it. French history textbooks, however, still highlight it today. Through this short paragraph, France was establishing a genuine archaeological protectorate over Egypt and reasserting the Frenchness of Egyptology.

From a purely political point of view, the 1904 agreements meant the general settlement of a long series of colonial conflicts. Since the mid-19th century, Egypt had been one of the French and British communities’ favourite arenas for confrontation. The French were envious of the British political domination, while the British felt aggrieved by the predominance of French, lingua franca on the banks of the Nile, and by the archaeological dominance of France, endorsed by the Entente Cordiale.

On 8 January 1905, an incident involving British officials and French tourists almost took an unpleasant political turn. What exactly happened is still a mystery; the French and British accounts of the facts differ so much that it’s hard to form an opinion. According to Howard Carter, the Antiquities Department’s Chief Inspector for Lower Egypt, who wrote a report now at the Griffith Institute, a group of French people ‘in a rowdy condition’ wanted to visit the Serapeum in Saqqara (an underground funerary complex devoted to the cult of the Apis bull). Some of them had refused to pay for a ticket, had forced their way into the site. Realising they didn’t have candles, demanded to be refunded, manhandling a guard in the process. Warned by the guards, Carter told the Frenchmen that if they didn’t leave ‘steps would have to be taken to remove them’. They didn’t take it nicely. When they finally left, after what sounds like a slapstick comedy episode, some of the guards were badly hurt, chairs had been broken, and Carter requested legal steps to be taken against these people.

According to the French version, however, they had paid for the tickets, and had only requested a refund when they had realised they didn’t have candles, and therefore no way of actually getting inside the monument. Carter, they said, had refused and instructed his staff to ‘drive these bloody French out’ and ‘hit them’.

What actually happened doesn’t really matter. The important bit is what was retained from the incident: in Egypt, where confrontations between the English and French communities frequently occurred, French tourists had been physically assaulted by a British member of the Egyptian civil service. In a very cordial spirit, of course.

Carter was fully aware of how embarrassing things could become. On the very day of the incident, rather than reporting back to his hierarchy, he sent a telegram to Lord Cromer. In agreement with Cromer, the Egyptian Foreign Minister decided to reprimand Carter for abuse of authority and to instruct him to apologise to the French Consul-General. Carter, not known for his diplomatic skills and sunny disposition, steadfastly refused to apologise, and pressed charges against the French tourists. The Egyptian Minister had to apologise himself, and to promise to punish the Egyptologist for disobedience – very cordially, of course.

On 17 January 1905, Howard Carter was transferred to Tanta, an unimpressive, industrial town in the Delta, about a hundred kilometres north of Cairo, with no interesting ancient monument in sight. This was not so much because of what he had allegedly done as because he had subsequently refused to do what was asked from him.

On 21 October, Carter resigned from the Antiquities Department. To help him out, Gaston Maspero, the Director of the Department, put him in touch with a wealthy British aristocrat who wanted to give archaeology a go – Lord Carnarvon; this led to the discovery we know and provided Carter with another opportunity to start a political crisis.

While language used in the ‘Saqqara Row’ had all the elements of a classic Anglo-French confrontation in Egypt, it shows the willingness of the French and British diplomats to avoid any scandal so shortly after the signing of the Entente Cordiale. All in all, the Entente seemed to work: the British Agent had penalised one of his countrymen, the French Consul-General had managed to keep the usually vindictive francophone press relatively silent, and everyone was happy – except poor Howard Carter. He had to cope with an isolated town, a crumbling house with bad drains and, to top it off, as he wrote to a colleague, ‘a bad summer, the average temperature being considerably above other years’.

This could never have happened in the previous century, in the golden age of Anglo-French rivalry – especially since anything egyptological was extraordinarily sensitive. The French have never really forgiven the British for having pinched the Rosetta Stone, you see…

[…] ‘Entente Cordiale’, you said? […]