In previous blogs we’ve explored how audio drama is perfectly suited to time travel and how our new audio dramas, Being and Not Being, were inspired by records from the Second World War in Swahili and Hindustani.

In this final blog we talk to the writers of Being and Not Being, Ery Nzaramba and Sharmila Chauhan, to get a sense of what it was like to encounter records at The National Archives and turn them into audio dramas. Their reflections provide powerful insights into a process that can at first sight appear mystifying.

- How do you approach the scale of the records we hold, and the challenge of seeking out the ‘right’ ones for the project?

- What do you do with the revelations in the records that challenge assumptions?

These kinds of burning questions led Ery and Sharmila in their creative responses. The allure of languages other than English gave them something to savour and respond to.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly they describe the power of seeing and working with original documents (not just copies), and the extraordinary ability records have to speak to generations many times removed from their creators.

How was your experience of working with The National Archives’ records?

Ery: A three-storey load of archives. Hundreds of years of British history. At my fingertips.

I pick up a folder. Dozens of pages. I want to read every one of them but know that if I did, I’ll have spent half a day reading a single folder, with possibly hundreds more to go through. So, I either pitch a tent in the reading room or… I learn to become selective.

Because, what today would be an email chain (or WhatsApp group) took immense proportions back then. A discussion on whether the word ‘soldier’ should also apply to natives, and whether ‘apply to’ should actually be replaced by ‘be affected by’, was a fist-thick folder of letters.

And the sheer amount of details. A native soldier taking the wrong soap, so to speak, would be reported to London.

I suppose that’s what it takes to run an empire.

Gradually some of the records at The National Archives are being digitised, although only titles are searchable. So, when I was searching for ‘KAR’ (King’s African Rifles) it was with the blind hope that ‘KAR’ appeared in the title of the document I was hoping to get. My research thus became a series of educated guesses leading to either the jackpot or a day gone up in smoke.

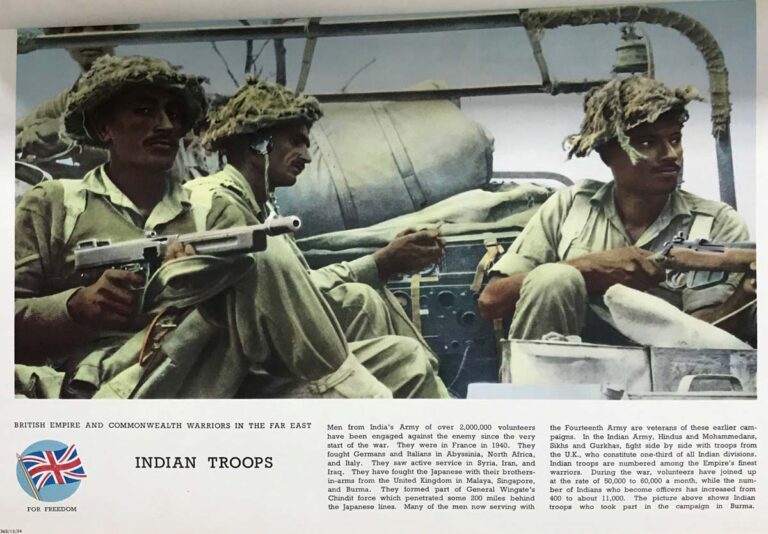

Sharmila: The materials came in a variety of forms. Large painted posters depicting men of the Empire hard at work in the war effort. Glamourous and captivating, they, like all good advertising, are pleasurable to the eye, whilst directing the subconscious to its true intention. (As in the one seen above.)

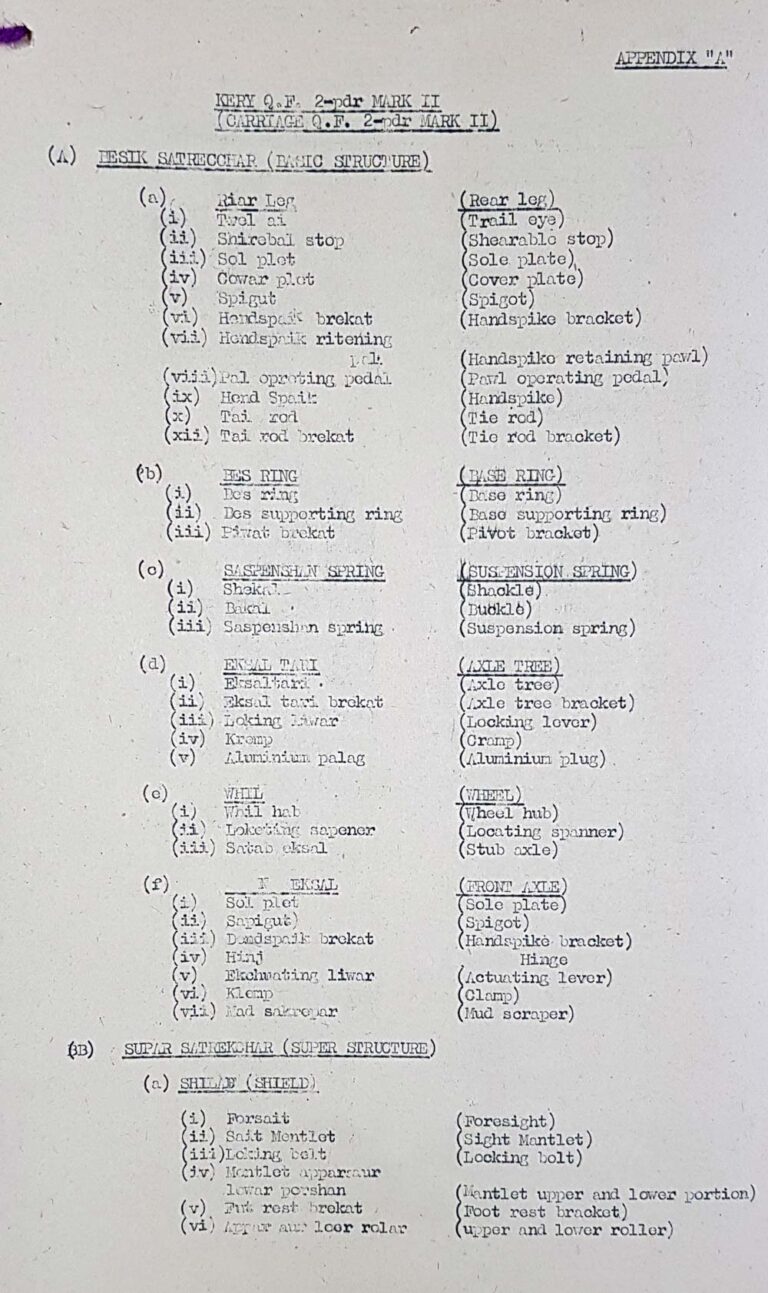

The textbooks were quite the opposite: black and white, they have innumerable pages. These were for the British personnel and contained translations of English military words into Hindustani. The utilitarian and comprehensive nature of these was unsettling.

This was a revelation. My understanding of colonial rule in India was that we had to learn English, and not the other way around.

Iqbal had picked out a text for me – a speech by a Major Tuker, both in English and then the translated Hindustani version. It used culturally specific terms around faith, duty and debt. This was not just simple translation, though: fighting a war requires something more than physical force, it requires heart-felt belief in the side you fight for.

I realised then that the British knew this and exploited Hindustani to capture the hearts and minds of the people of (undivided) India.

How did the records inspire you?

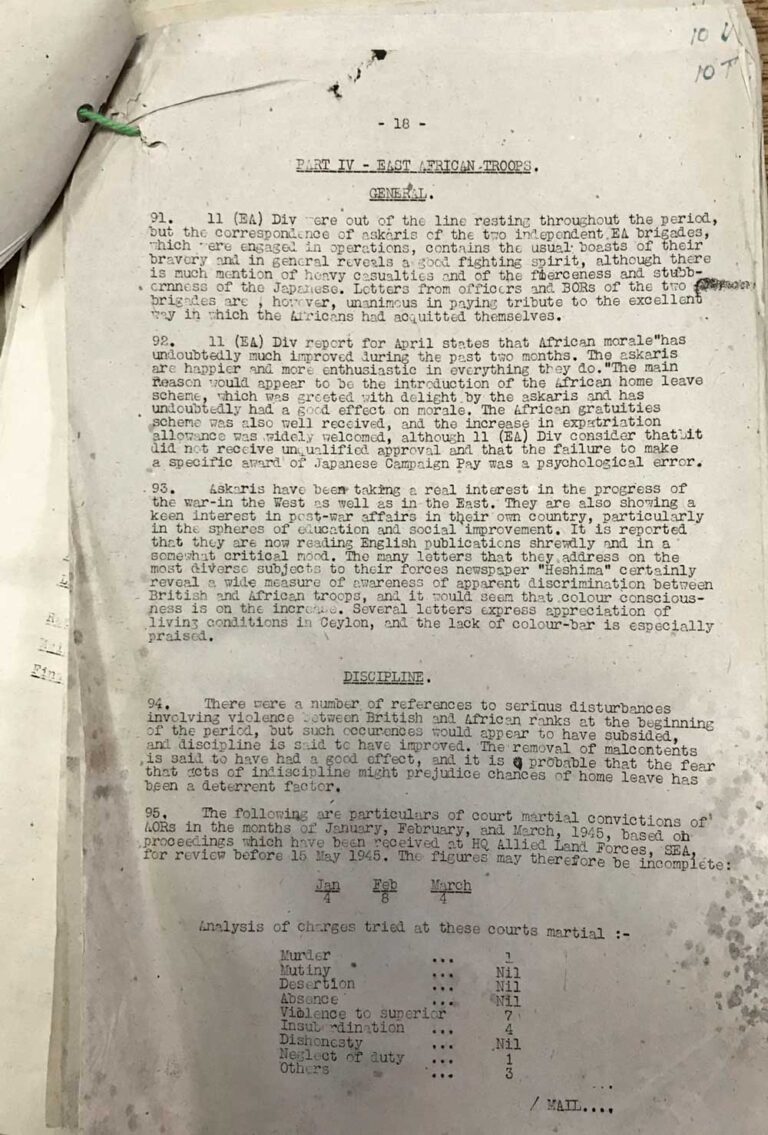

Ery: I was looking for the personal in a sea of administrative documents and the series of ‘Quarterly Reports on the Morale (of the troops)’ was the closest I got to hearing the African soldiers’ own voices. These were summaries of the native troops’ ‘thoughts’, gathered from their (censored) letters, among other things.

One ‘thought’ kept recurring – namely their consternation and fear of ‘Kiswahili spreading back home’. This gave me the key questions around which I was going to develop the play:

Why were the East African troops in the Colonial army against Kiswahili (as opposed to English) and what if Kiswahili had become the lingua franca of Africa (instead of English)?

Sharmila: As a child of Indian parents, Indian music and film was a significant part of my childhood. The language was lyrical and poetic, full of unrelenting (sometimes very dramatic!) emotions. For me, it was the language of love – romantic, familial, spiritual.

At the time my parents referred to the language as Hindi. But through reading the documents and discussion with Iqbal, I realised that it was actually Hindustani, not Hindi.

With extremism on the rise in South Asia, I found it inspiring to understand that at one point there were several languages that joined communities across faith lines. But the fact that the British had co-opted Hindustani, a language of poetry and love, as the language of war inspired me to try to create a piece of work exploring both sides of this beautiful language.

What did you learn through close contact with historical documents?

Ery: I’m touching the paper that’s gone yellow with time… I look at the typos, the handwritten comments… I’m seeing the typewriter by now, the person typing… I’m imagining their surroundings, the time of day, the smell in the room (they’re smoking)… I basically have a movie going on in my head, one I would have never got by reading a copy of the exact same document.

I never knew how much difference it makes, to have direct contact with actual historical material.

Sharmila: The differing formats of the documents said so much about the way Hindustani was used by the British. Some were subliminal through visuals, others were handy pocketbooks for use in the field, others were official government documents for speeches. Seeing them physically together in a quiet room took away some of their sinister power, but also distilled it.

And so, in that small room, decades after the fact, a writer of South Asian heritage tells the story of a language exploited by the British, in English. The irony of it is not lost to me. However, in the circularity of language, perhaps this is the way the language flows, around and through, knitting the past and present together.

A big thank you to Ery and Sharmila for sharing their thoughts. You can listen to Being and Not Being on SoundCloud.