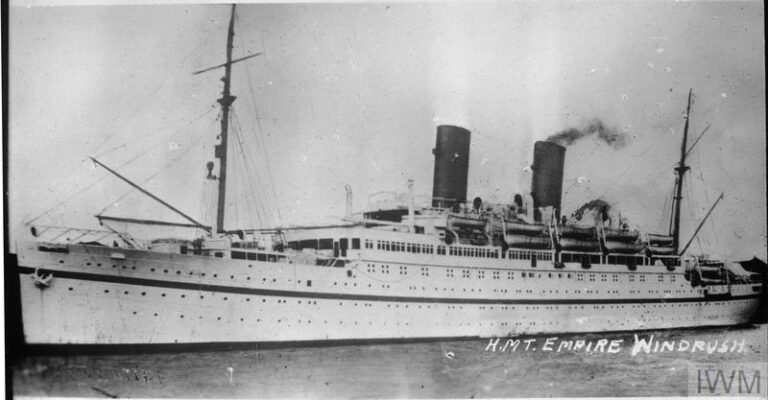

On 22 June 1948, the Empire Windrush arrived at Tilbury docks in Essex. Departing from Kingston, Jamaica, there were over 1,000 passengers onboard the ship, including Ena Clare Sullivan. Records held at The National Archives provide a unique insight into Sullivan’s story after she disembarked at Tilbury, and her subsequent career as a nurse.

The National Archives holds a large amount of material on the Empire Windrush, and post Second World War migration to Britain more broadly. However, it is important to note that these records were created by the government, and are from the government’s perspective. As a result, the records we hold about Sullivan are largely official documents produced by government departments related to her life in Britain. The records do not provide us with information on how she personally felt about her life in Britain, the challenges she likely experienced because of her Jamaican heritage, and her memories of working as a nurse.

Researching the lives of women who migrated to Britain can be challenging. As is often the case with women’s history, it is not always possible to trace an individual’s story, and it can be hard to find women’s voices in the archives. A woman’s surname could also change if she married, which could cause further difficulties when trying to trace a particular individual.

The creation of the NHS

On 5 July 1948, in the same year that the Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury, the National Health Service (NHS) was established. An unprecedented number of healthcare workers were needed to staff Britain’s new health service.

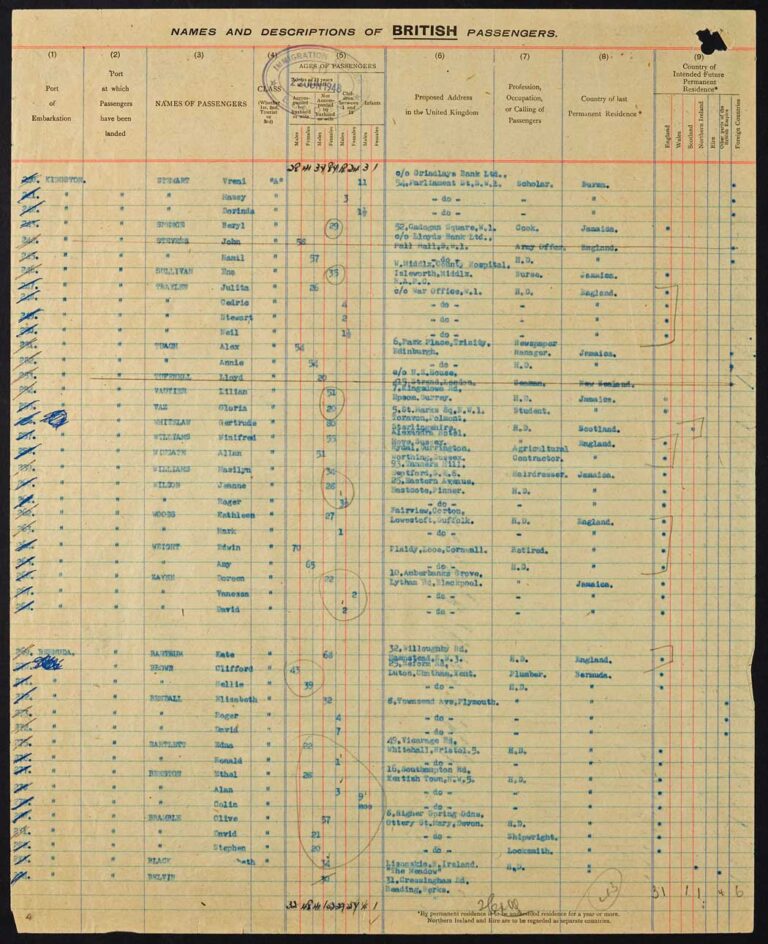

Consequently, the British government began to recruit doctors, nurses and healthcare workers from Commonwealth countries and its colonies. Many passengers who migrated to Britain after the Second World War would go on to work for the NHS. Indeed, Sullivan was one of seven passengers on the Empire Windrush who listed their occupations as ‘Nurse’. Of these seven, six were female and one was male.

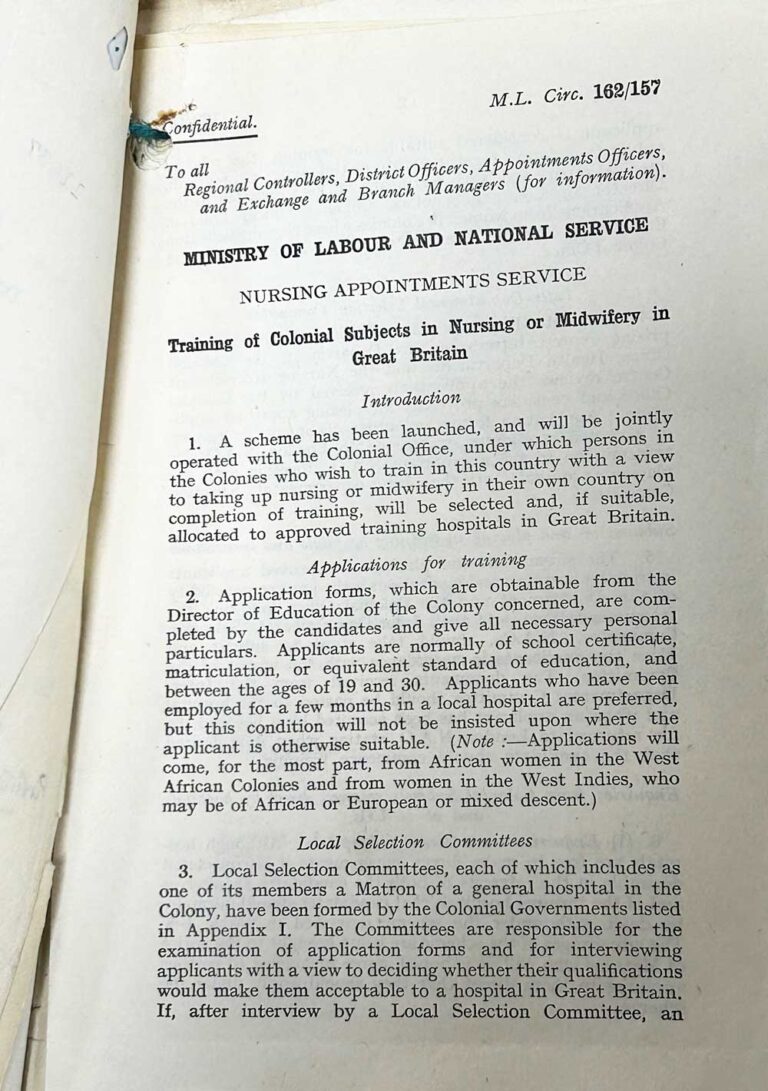

During this period, the Ministry of Labour and National Service and the Colonial Office introduced a scheme called the ‘Training of Colonial Subjects in Nursing or Midwifery in Great Britain’. The scheme enabled individuals in the colonies to apply, and if successful, to train as a nurse/midwife in Britain. It is therefore likely that Sullivan travelled to Britain on this scheme.

Travelling to Britain on the Empire Windrush

The passenger list for the Empire Windrush provides some useful information on who Sullivan was, including that she travelled in class ‘A’ (see footnote 1). There were three types of tickets for passengers, ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’. Class ‘A’ was the most expensive type of ticket at £48 (around £2,000 in today’s money). This suggests that Sullivan or her family were wealthy enough to pay this type of fare. Having an ‘A’ class ticket also meant that Sullivan would have had a private cabin for the journey.

It also records that Sullivan was born in 1913 and was 35 years old at the time of travelling. It is likely that she travelled alone, as she is not listed as travelling with relatives, nor did anyone have the same onward address as her. Her last residence was listed as Jamaica and her proposed onward address was ‘West Middlesex County Hospital’ in Isleworth, West London (see footnote 1).

Training as a nurse

From studying the passenger list alone, it is unclear whether Sullivan trained as a nurse in Jamacia or was planning to undertake training in Britain. The Register of Nurses, held by the Royal College of Nursing (and available online through Ancestry, which can be accessed for free on-site at The National Archives) provides some clarity on this.

In 1919, the Nurses Registration Acts were passed which created a register of qualified nurses. It was subsequently made a legal requirement for all nurses to register after they qualified under the 1943 Nurses Act (see footnote 2). As a result, the Register of Nurses can help researchers trying to trace individuals and provides useful information on where nurses trained or gained their qualifications from.

Sullivan’s entry shows that she registered as a nurse on 3 December 1951 and trained at ‘West Middlesex Hospital, Isleworth’ (see footnote 3). This appears to suggest that Sullivan did not train as a nurse in Jamaica, but in Britain. However, it must be noted that a large number of Caribbean migrants had to undertake additional training once they arrived in Britain, even if they had already qualified overseas, as their qualifications were often not recognised by the British system (see footnote 4). We cannot know for sure if this was the case for Sullivan, or whether she was employed in a different field of work before travelling to Britain to train as a nurse.

West Middlesex Hospital had a large training school for nurses, which Sullivan attended. In May 1948, a hospital inspector’s report produced by the General Nursing Council for England and Wales praised the school for its ‘excellent material for training student nurses’ (see footnote 5). The same report stated that there were 330 female student nurses and 40 male student nurses training at West Middlesex Hospital. Most students lived in accommodation provided by the hospital. In total, there were nine nurses’ homes within the hospital grounds, the largest home housing 157 students (see footnote 6). Although this report was produced a month before Sullivan arrived at Tilbury Port, it provides an interesting insight into what Sullivan’s training and accommodation would have been like.

The image below, taken from a booklet produced by West Middlesex Hospital in the early 1960s, depicts the nurses’ station, an area that nurses could work behind when not dealing directly with patients.

The London Electoral Registers, held by the London Metropolitan Archives (and available online through Ancestry), allow us to trace where Sullivan was living during this time. In 1951, Sullivan was recorded as living with George Pothecary and Norah B Pothecary at 131 Twickenham Road, which was located opposite West Middlesex Hospital (see footnote 6).

She would likely have qualified as a nurse by this point, so was no longer living in the accommodation for student nurses. As the accommodation was owned by the hospital, it is probable that the Pothecarys also worked at the hospital. Sullivan was later recorded as living with other healthcare professionals at Twickenham Road (east side), which was part of West Middlesex Hospital, in 1954 and 1956 (see footnote 7).

Registering her British nationality

The 1948 British Nationality Act created the status of ‘Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies’, which meant that anyone who had previously been considered a ‘British subject’ was given the status of ‘citizen’. In effect, this meant that whether you were born in Britain, a British colony like Jamaica, or an independent Commonwealth country like Canada, everyone had the same legal rights in Britain.

The new legislation around citizenship and the increasing need for labour after the Second World War encouraged a significant number of people to migrate to Britain. Although the British Nationality Act was passed on 12 July 1948, around three weeks after Sullivan arrived in Tilbury on 22 June 1948, Sullivan and her fellow passengers onboard the Empire Windrush largely travelled in response to news about the new law. As Sullivan was born in Jamaica, a British colony, she was a ‘Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies’, and thus had the right to live and work in Britain.

In 1962, however, the Commonwealth Immigrants Act was passed, which limited the freedom of movement for citizens born outside of Britain. As Sullivan was by this time already living and working in Britain, and had been for over a decade, this change in the law did not directly affect her. Nonetheless, this may have encouraged Sullivan to register her British nationality in 1968.

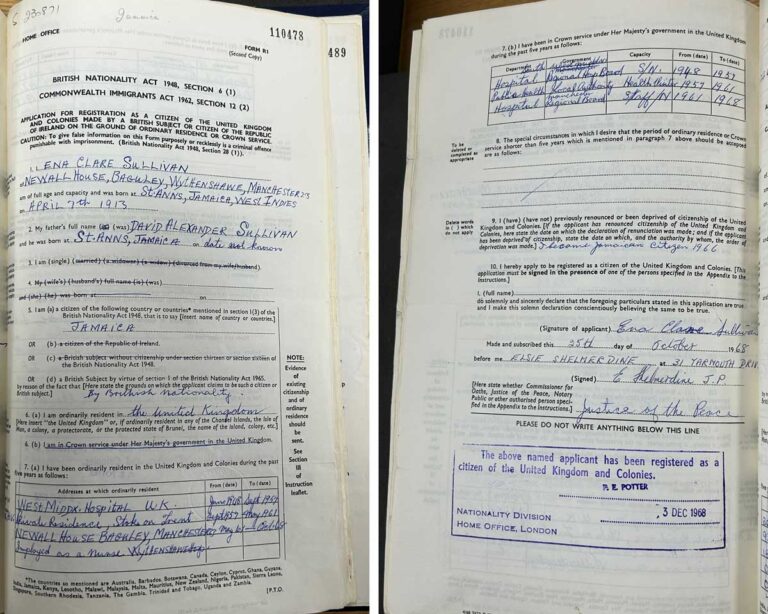

Sullivan’s registration of British nationality is a particularly rich record, as it reveals a significant amount of information about her story, most notably her family, employment history, and the places she lived. Her application notes that she was born in St Anns in Jamaica on 7 April 1913 and that her father was called David Alexander Sullivan, and was also born in St Anns, Jamaica. We also learn that she remained ‘single’ (see footnote 8).

From June 1948 to September 1959, Sullivan’s address is recorded as ‘West Middx. Hospital UK’ and her place of work as ‘South West Middlesex Hospital’. She is an ‘S/N’, which most likely refers to staff nurse (see footnote 8). As Sullivan worked at this hospital for 11 years in total (she qualified in 1951 after training for three years), Sullivan then continued to work at the hospital for a further eight years after qualifying.

Sullivan’s address between September 1959 to May 1961 is listed as ‘Private Residence, Stoke on Trent’. She also worked as a ‘Health Visitor’ for the ‘Local Authority’ (see footnote 8). Although we do not know why Sullivan moved to Stoke-on-Trent, her new role as a health visitor would have been quite different to working in a hospital setting. As a health visitor (a qualified nurse who works largely in the community), Sullivan would have spent a large amount of her time visiting people in their homes.

Her final address from May 1961 to October 1968 is noted as ‘Newall House Baguley Manchester Employed as a Nurse Wythenshawe’. Her job is recorded as ‘Staff/N’, again most likely short for staff nurse at Wythenshawe Hospital in Manchester (see footnote 8). It seems that Sullivan’s commute to work was relatively short, as the hospital was around a 25-minute walk from where she lived.

The bottom of the record shows that Sullivan’s application was approved on 3 December 1968, meaning that she successfully registered her British nationality. It has not been possible to trace Sullivan’s life further than this. And yet, as she registered her British nationality, it is likely that Sullivan planned to continue living and working in Britain after 1968.

The National Archives’ records offer a fascinating insight into Sullivan’s story. They allow us to trace her nursing career over a twenty-year period and the significant contribution she made to the newly formed NHS. Whilst these records cannot tell us how Sullivan personally experienced living and working in Britain, official government records can still provide us with an understanding of who Ena Clare Sullivan was.

We’ll soon be revealing our plans to mark the 75th anniversaries of the Empire Windrush’s famous arrival and the foundation of the NHS. Follow our social media channels and sign up to our mailing list to find out more.

Footnotes

- Passenger list for the Empire Windrush, 1948, BT 26/1237/91, The National Archives.

- ‘State registration for nurses’, Royal College of Nursing, https://www.rcn.org.uk/library/archives/Family-history (accessed 24 February 2023).

- The General Nursing Council for England of Wales: Register of Nurses, 1 September 1951 – 31 December 1951, Royal College of Nursing, p. 64, accessed via Ancestry.

- Online exhibition: ‘Heart of the Nation: Migration and the Making of the NHS’, Arrival text, The Migration Museum, https://heartofthenation.migrationmuseum.org/arrival/ (accessed 24 February 2023).

- ‘Report on Visit to Hospital’, 12 May 1948, DT 33/624, The National Archives.

- Electoral Register for London, Heston and Isleworth Borough Constituency, 1951, MR/PER/C/0853, London Metropolitan Archives, accessed via Ancestry.

- Electoral Register for London, Heston and Isleworth Borough Constituency, 1954, MR/PER/C/0902, London Metropolitan Archives, accessed via Ancestry; Electoral Register for London, Heston and Isleworth Borough Constituency, 1956, MR/PER/C/0978, London Metropolitan Archives, accessed via Ancestry.

- Ena Sullivan’s Registration of British Nationality, 3 December 1968, HO 334/1406/110478, The National Archives.

I enjoyed reading about nurse Ena Clare Sullivan’s experience in Britain where she made a significant contribution to the health of the British people.

I remember Queen Mary’s Hospital, Carshalton located in London Borough of Sutton. Alas gone now.

I had my appendix out at that hospital when I was about 12, which would make the date 1953. The most wonderful nurse I had was West Indian. She was caring and gentle and had a lovely lilt to her voice. I now wonder if she was one of the ‘Windrush’ nurses.

Thank you for sharing this memory. It’s difficult to know if she was a passenger on the Empire Windrush without knowing her name, but she was likely part of the Windrush generation.

Interesting story! Also see Nursing A Nation: An Anthology of African and Caribbean Contributions to Britain’s Health Services compiled by Jak Beula.

Thanks for your comment and for the book recommendation.