One of the highlights of the suffrage centenary so far has been the unveiling of a statue commemorating the achievements of Millicent Fawcett – President of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies – in Parliament Square. Importantly, she is the first woman to be immortalised in bronze within the confines of this iconic square. However, she is not the first woman or suffrage activist to have been memorialised within sight of the Houses of Parliament. That was Emmeline Pankhurst; her memorial has been situated within Victoria Tower Gardens and has stood in the shadow of Parliament since 1930.

Emmeline Pankhurst, women’s suffrage campaigner and leader of the Women’s Social and Political Union, died on 14 June 1928 – only weeks before equal franchise passed into law. However, her contribution and commitment to the suffrage campaign ensured that she would have a permanent association to women’s equality.

Calls to erect a memorial to Pankhurst quickly followed her death. On 29 June 1928, Katherine ‘Kitty’ Marshall, a former member of Pankhurst’s bodyguard and the WSPU, enquired how best to proceed with erecting a statue in the memory of Mrs Pankhurst in the neighbourhood of the House of Commons. As detailed within a memorandum, Marshall’s initial suggestions for possible locations of this statue were either on the green adjoining the gardens of 10 Downing Street, or alongside the statue of Oliver Cromwell within the grounds of the House of Parliament. She was informed of the procedures she needed to follow and the likelihood that her plans would need to also be approved by the Royal Fine Art Commission. In response she replied that her group possessed enough support to acquire any site it chose.

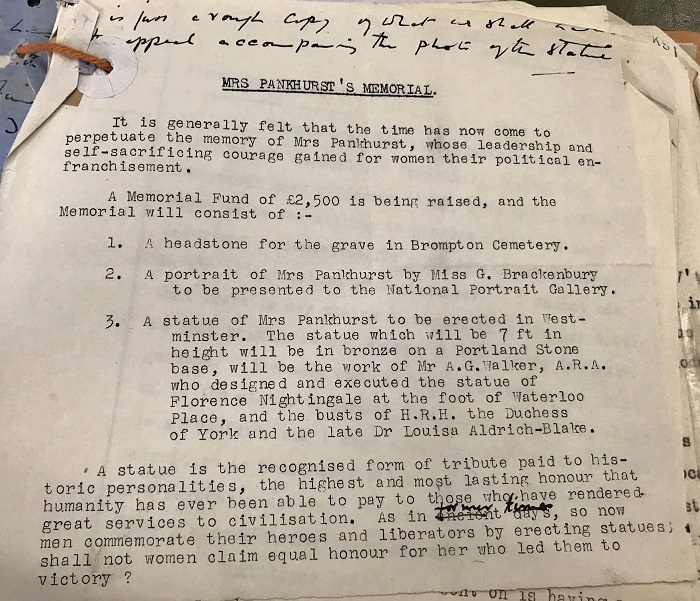

Marshall represented a group of former suffragettes who had established the Pankhurst Memorial Fund. With Flora Drummond acting as its Chair and Lady Rhondda as its Treasurer, the group’s conviction to their task could not be questioned. They had three main objectives. The first was to fund a headstone for Pankhurst’s grave in Brompton Cemetery. Secondly, they aimed to present the National Portrait Gallery with a painting of Pankhurst by Georgina Brackenbury. Finally, they sought the erection in Westminster of a seven foot bronze statue designed by Arthur George Walker. Walker had been chosen on account of his sculptures of notable women, which included a statue of Florence Nightingale that was unveiled in 1915.

Memorandum by Kitty Marshall concerning Emmeline Pankhurst’s statue, 1928-1930. Reference: WORK 20/188.

The records relating to the proposed memorial statue fall silent until 12 November 1928. However, a memorandum written by Sir Lionel Earle, permanent secretary to the Office of Works, suggests that Marshall and her group had been active in attempting to gain government support and finalise a location. His note outlines the way that Marshall and her colleagues had been unsuccessful in their efforts to arrange an interview with the Prime Minister regarding their aims. The proposed sites had also been revised, with Victoria Tower Gardens replacing the idea to erect the statue alongside Oliver Cromwell.

However, even at this relatively early stage there was a reluctance within government to see the project come to fruition. Earle took the opportunity to suggest that Manchester, Pankhurst’s birthplace, might be a more appropriate location. Marshall immediately responded: ‘Oh, but we are going to have a statue to her there as well’. But the draw of a Westminster setting lay chiefly in the fact that it was ‘was the principal battleground of the suffragettes’.

Writing on 27 November to the First Commissioner of Works, Earle describes Marshall as ‘tiresome’ and argues that a lack of precedent for similar statues – those to social reformers – be used as a reason to block these plans. Similarly, the argument used to justify the Westminster location was turned on its head by Earle. He suggested that the First Commissioner might wish to discuss with other colleagues in Cabinet ‘as to the propriety of a statue to that lady being placed in Westminster at all’. His terminology clearly suggests a lingering bitterness over actions that had taken place more than a decade previously.

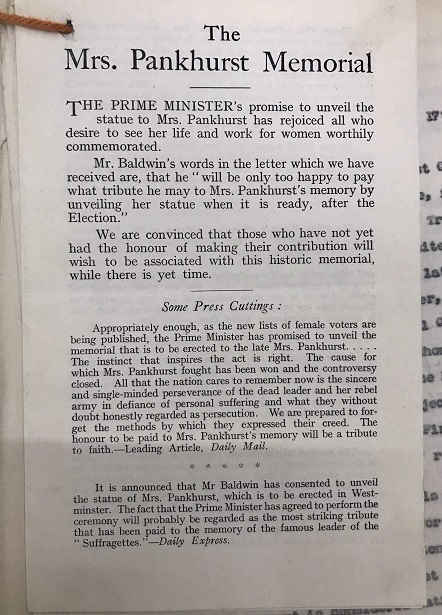

Correspondence between the two groups continued until it was announced in January 1929 that the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, had agreed to unveil the statue. The Prime Minister’s endorsement and public support of the project was well received, with many of the national papers reporting the announcement. The Daily Mail wrote: ‘The instinct that inspires the act is right. The cause for which Mrs Pankhurst fought has been won and the controversy closed. All that the nation cares to remember now is the sincere and single-minded perseverance of the dead leader and her rebel army in defiance of personal suffering…’

Memorial leaflet

While the statue had been announced, its location was still undecided. However, following the Prime Minister’s public patronage, the Office of Works immediately became more invested and paid both Marshall and the project greater attention.

Following Marshall’s submission of a photograph of the scale model, plans and dimensions, Victoria Tower Gardens was chosen as the site. The statue would be clearly visible from the road and within a close enough proximity to the Houses of Parliament. There were a few minor tweaks to the proposed design that needed to be carried out. In its current state, the Royal Fine Art Commission felt the design of the pedestal was too large and advised that it should be situated towards the west of the gardens, rather than a central location. Lord Londonderry, the First Commissioner of Works, confirmed that the site of Victoria Tower Gardens was acceptable on the proviso that the requested changes be made. The final proposals did not get full approval until the beginning of 1930.

The memorial was formerly unveiled on 6 March 1930 against a backdrop of choral music and in front of a large gathering of dignitaries, former suffragettes, and members of the public. Stanley Baldwin, Flora Drummond, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence MP, and Lady Rhondda all spoke at the unveiling ceremony, before wreaths were laid.

In the 1940s Mrs Pankhurst’s Statue Plant Fund Appeal was established to guarantee funding would be in place for plants around the memorial. Reference: WORK 35/335.

However, the memorial to Emmeline Pankhurst has evolved, both physically and metaphorically, over the years. In 1956 the memorial was moved to a new location within Victoria Tower Gardens. In 1959 the statue was altered to accommodate the addition of a memorial to Emmeline’s daughter, Christabel, and the other members of the WSPU. Metaphorically, the memorial quickly turned into a site that more generally represented the suffragettes. Former suffragettes flocked to the memorial around Pankhurst’s birthday. In the 1940s, to ensure the legacy of the suffragettes lived on, a ‘Mrs Pankhurst’s statue plant fund appeal’ was established to guarantee that funding would be in place to ensure a flower was constantly in a vase in front of the statue.

Without the tireless actions of Kitty Marshall and the other members of the Pankhurst Memorial Fund, the memorial to Emmeline Pankhurst would not have been erected as quickly. Collectively, they demonstrated the same passion and resolve that was fundamental to achieving partial enfranchisement in 1918. The campaign was also about publicly recognising the acts of women. As Marshall eloquently summarised: ‘Men commemorate their heroes and liberators by erecting statues, shall not women claim equal honour for her who led them to victory?’

Statue of Emmeline Pankhurst: watercolour sketch showing proposed re-siting in Victoria Tower Gardens, 1958. Reference: WORK 35/335

The Citizens project is led by Royal Holloway, University of London, and charts the history of liberty, protest and reform from Magna Carta to the Suffragettes and beyond.

Steven Franklin is a Citizen’s Project Officer.