A new online collection offers people interested in history unprecedented and extensive access to Queen Elizabeth I in her own words. It contains 40 unique documents from The National Archives’ collection, each transcribed and available to read in high definition.

The records cover the broad span of Elizabeth’s reign, and themes such as the marriage question, her relationship with Mary Queen of Scots, foreign policy and the poor law. They reveal her as sovereign in a male world. The collection has been especially curated, interpreted and introduced by leading Tudor expert Tracy Borman, author of ‘The Private Lives of the Tudors: Uncovering the Secrets of Britain’s Greatest Dynasty’.

These documents on the age of Elizabeth I can be used by teachers looking for resources to support the new GCSE specifications in history, published last year and expanded to cover the Tudor period, and anyone studying the Tudors at A level.

Coram Rege Rolls, initial detail Elizabeth I, 1581 (catalogue reference: KB 27/1276)

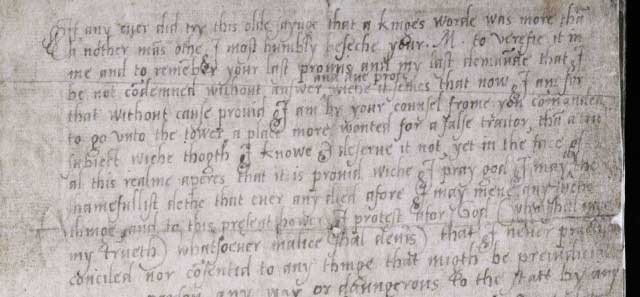

The ‘Tide Letter’

Some of Elizabeth’s earliest letters presented here reflect the reality of her precarious time as princess. This includes the famous ‘Tide Letter’, written to Queen Mary I before Elizabeth was to be imprisoned in the Tower of London, on suspicion of her involvement in a plot led by Sir Thomas Wyatt to make her queen.

Elizabeth inserted lines between where her text finished and her signature to ensure that her enemies could not add any more writing. It was called the ‘Tide Letter’ as she wrote it slowly in order to delay her transport to the Tower, which would have required a low tide.

Education

This life in documents also provides a window into Elizabeth’s education and intellect. Again, the ‘Tide Letter’ itself, written in beautiful Italianate [italic style] handwriting, provides unwitting testimony to her early teaching from humanist-influenced scholars. Indeed, her tutor for Italian, Giovanni Battista Castiglione, remained with her during her imprisonment.

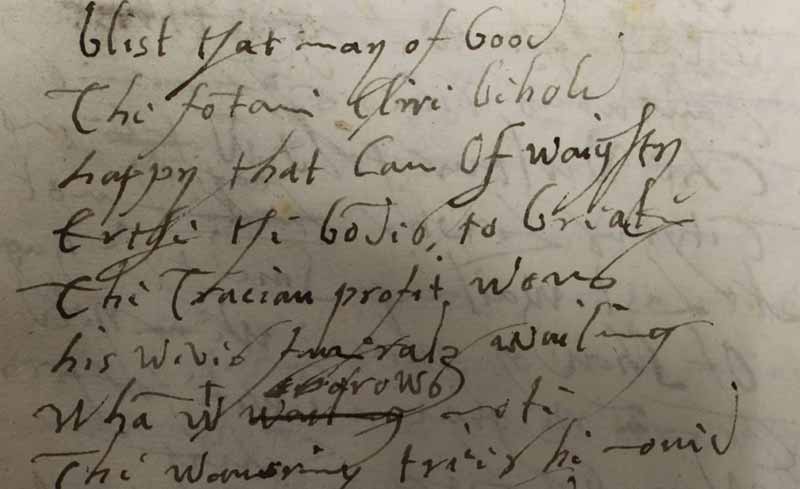

Elizabeth I also enjoyed studying Latin and Greek throughout her life, and our collection also provides an extract of her own translation of Boethius’s De Consolatione Philosphie (The Consolation of Philosophy) made in 1593, towards the end of her reign.

Elizabeth’s translation of Boethius’s De Consolatione Philosophie, 1593 (catalogue reference: SP 12/289 f.48)

Elizabeth I’s Second Great Seal

Elizabeth I’s first speech to parliament shows her resolve from the start of her reign. She promised ‘to direct all my accions by good advise and counseill’ and much more.

Great Seal of Elizabeth I, 1586-1603 (catalogue reference: SC 13/N3)

Interestingly, an image of the later Second Great Seal offers a glimpse into how confidence in her own authority to rule as a woman evolved. This object is overloaded with symbolism, confirmed by its inscription: ‘Elizabetha dei gracia Anglie Francie et Hibernie Regina Fedei Defensor’ (that is, ‘Elizabeth, by grace of God, Queen of England, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith’). It is naturally a brilliant example of royal propaganda: Elizabeth – flanked by Tudor roses, coats of arms and holding the orb and sceptre – was every inch the anointed queen.

We can also get a sense of her character from a letter written to her young favourite, Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex regarding his naval campaign against the Spanish in 1597:

‘eyes of youth have sharpe sightes, but commonlye and not soe deep, as those of elder age which makes me marvayle lesse.’

And in an earlier recorded response to parliament, appreciate her disdain in discussing the marriage question as ‘whither it was fit that so great a cause as this shuld have had his beginning in suche a public place’.

Mary Queen of Scots

Elizabeth’s relationship with Mary Queen of Scots will be a familiar story to students of the period. What may not be so familiar is a letter to Elizabeth dated in March 1565 and dictated by Mary, written in broad Scots. The letter gives an account of the murder of David Rizzio, Mary’s Italian secretary, at Holyroodhouse. The murder took place in Mary’s presence, and in the letter she states that she is too tired and upset to write after escaping and riding hard for five hours in the middle of the night while sick and pregnant.

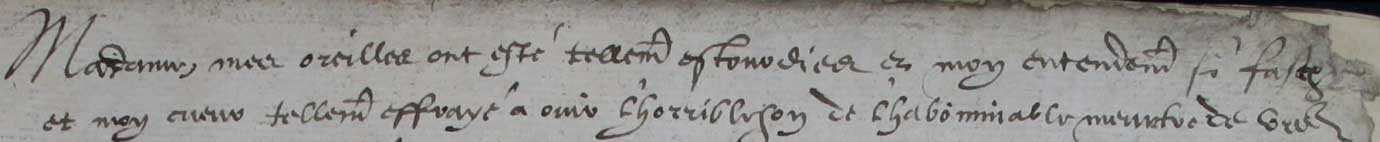

Associated with these events, and another interesting read, is Elizabeth’s response to the subsequent news of the death of Mary’s husband, Lord Darnley, which begins:

‘My ears have been astounded and my heart so frightened to hear of the horrible and abominable murder of your husband.’

Elizabeth I to Mary Queen of Scots, 24 February 1567 (catalogue reference: SP 52/13f.17)

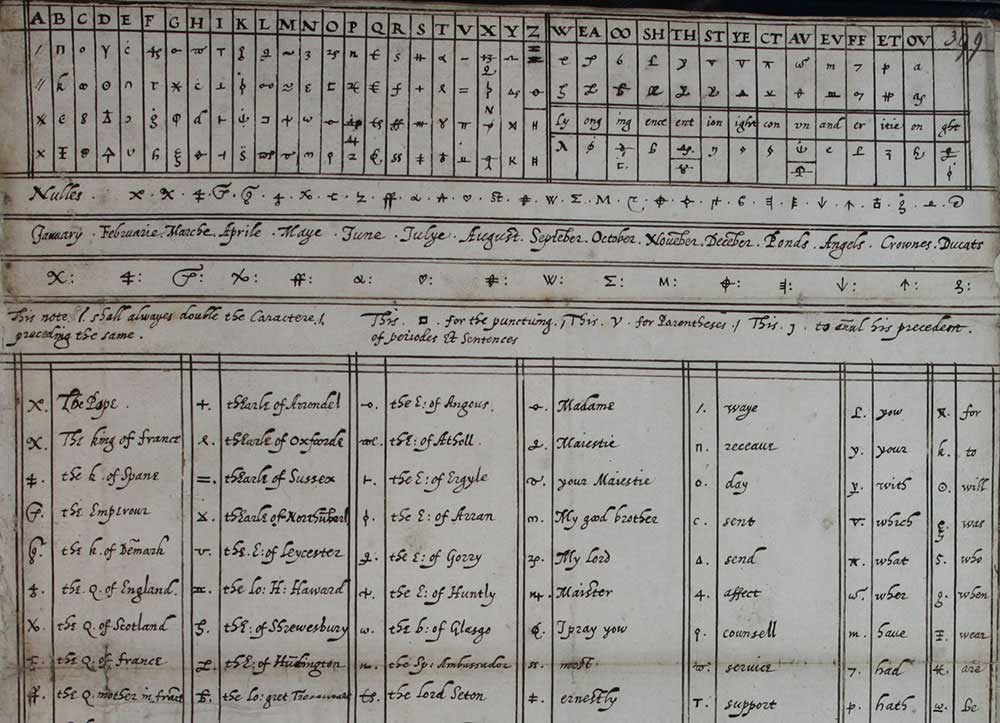

A further record which perhaps helps to convey a sense of this climate of fear is a page of ciphers found in Mary’s possession at time of the Babbington plot, a Catholic conspiracy to depose Elizabeth I and put Mary on the English throne.

According to Tracy Borman, for this particular example symbols are substituted for letters in particular words, and the names include the Pope, Bess of Hardwick and the Earl of Hertford and his sons; the latter were potential rivals for the English throne. Sir Francis Walsingham, principal secretary of state from 1573, controlled a tight network of spies to protect the Elizabethan state and succeeded in uncovering the plot in 1586.

Page of ciphers used by Mary Queen of Scots, c.1586 (catalogue reference: SP 53/22 f.1)

Edmund Campion

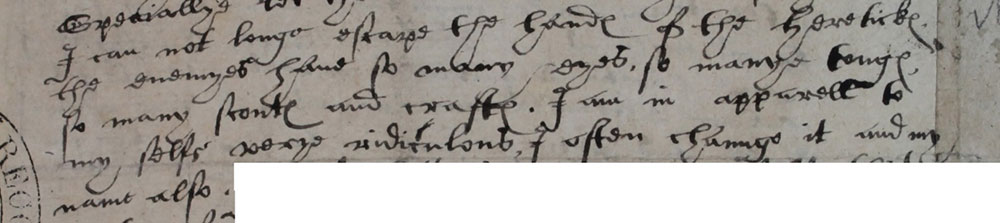

A letter from the Catholic priest Edmund Campion in 1580 provides evidence of the dangers faced by Catholic priests and restrictions on the practice of their religion. Campion wrote that:

‘I can not longe escape the hands of the heretickes the enemies have so many eyes, so many tonges, so many scoutes. I am in apparel to my selfe verye ridiculous, I often change it and my name also.’

Letter from Edmund Campion to a friend (possibly Dr Allen), 1580 (catalogue reference: SP 15/27B f117)

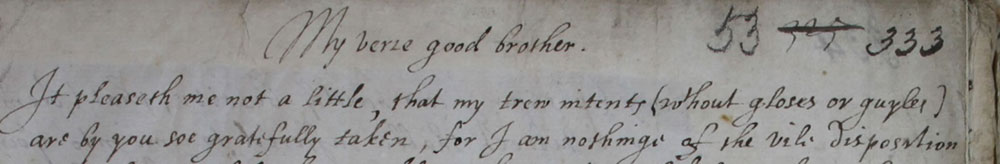

Last letter written by Elizabeth I

The final letter in the collection, written in January 1603, is the last ever written by Elizabeth I. She wrote to James VI of Scotland, the man who would succeed her to the English throne. The letter reveals their closeness and mutual respect as she penned:

‘My verie good brother. It Pleaseth me not a little, that my trew intents (without gloses or guyles) are by you soe gratefully taken’.

Even though her health was failing her at this point, she makes no formal offer to name him as her heir and signs off as his ‘loving and friendly sister’.

Elizabeth I to James VI, 5 January 1603 (catalogue reference: SP 52/69 f.53)

There are of course many other documents that could have been chosen to represent an insight into the world of the Elizabethan state, but this substantial online collection goes a long way in signposting students, or anyone interested in England under Elizabeth I, towards some of its key themes and events through the words of the monarch and her contemporaries.

Holyroodhouse is spelt as one word, can it please be corrected.

Hi David,

Thanks for your comment – the blog has been corrected.

Best,

Nell

Hi –

I think the Campion letter should say:

‘I can NOT longe escape the hands of the heretickes …’

Hi Mick,

Thanks for your comment – the blog has been updated.

Best,

Nell

Brilliant blog. Thank you for sharing.

Really interesting post – love the detail. The source documents are amazing.

I work as a voluteer in a Tudor property and next year i would like to do an event about codes and cyphers. Can you suggest where i can get some more information please.

This is not British history, it is English history assumed as usual to cover the entire island of Britain. It should be called: The Private Lives of the Tudors: Uncovering the Secrets of England’s Greatest Dynasty’.

Scotland had its own monarchs at that time.

This brings up an old question, should the present Queen, not be called Queen Elizabeth I of Scotland, as she is the first Elizabeth queen, not the second, to rule Scotland?

In Edmund Campion’s letter, there are two more words after “so many scoutes” and before “I am in apparel” that are missing from the transcript and from its own page. The first word is surely another “and” followed by a word of six or so characters.