The Victorian period saw the introduction of countless imaginative and bizarre electronic devices that promised to transform lives as theoretical understandings of electricity developed. Sensationalist lectures and demonstrations involving electricity became really popular forms of entertainment in the period, drawing large crowds. As this blog will explore, the allure of electricity permeated 19th-century consumer culture and even understandings of the body.

By the end of the preceding century the phenomena of electricity was becoming better understood, with the likes of Benjamin Franklin’s experiments with the Leyden jar (a glass jar that stored electric charge) and Luigi Galvani’s experiments sending electricity through dead frogs – leading him to propose that the nervous system delivered electricity to muscle (a prospect that would go on to inspire Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’) (see footnote 1).

The 19th century continued to see a number of notable discoveries and inventions, including Alessandro Volta’s invention of the Voltaic Pile, an electric battery that produced a steady electric current, and Michael Faraday’s invention of the electric motor, that could convert mechanical energy into electricity on a large scale. Following these developments in scientific understanding, the Victorian period witnessed a new electrical age.

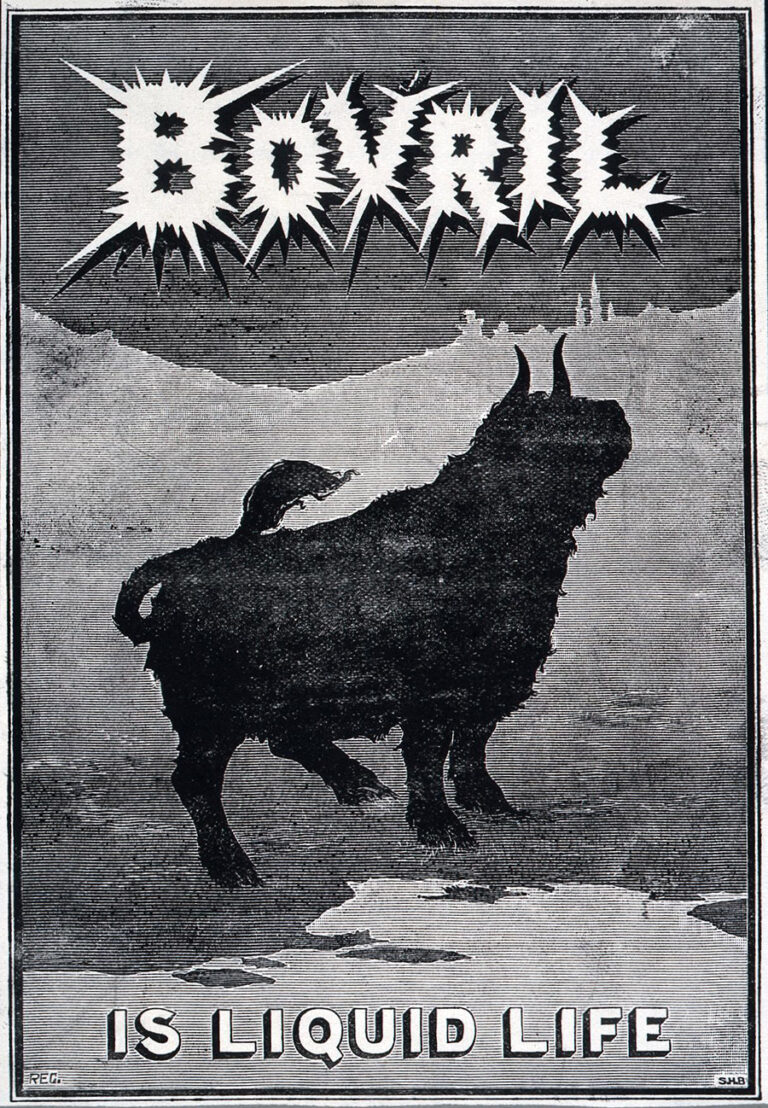

Electricity was so pervasive within Victorian culture that even promotional material for food items like Bovril tried to evoke a connection to electricity as an energy source (the ‘vril’ is a reference to a 19th century scientific-fiction novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton in which the ‘Vril-ya’ had electrical powers).

Electricity and medical practice

Electricity was used for a multitude of ingenious inventions, from lighting to use in telegraph communications. Records found within our registered designs collections in BT 45 illustrate just some of the products that began to appear on the market. Notably there were a proliferation of electro-therapeutic devices in the period, such as Gabriel Davis’s ‘Graduated Medical Galvanic Machine’ (1847), Matthews Brothers’s ‘Pocket Magneto Electric Machine’ (1870), and Dr John Ambrose Fleming’s ‘Medical Battery’ (1883). These products were likely used to send a current through the body to theoretically restore the vital forces.

In the 18th century, the theory of vitalism – that living creatures contained a ‘vital principle’ or distinct life force, making them different to inanimate objects – became part of medical practice. This vital force (which was also equated with the soul) was later linked to electromagnetic energy, leading to the use of electric and magnetic devices being seen to restore or revitalise the body’s natural electricity. In opposition to vitalism was a mechanical view of the world, with treatment tending to be more interventionist, such as through the use of medicine.

Electric devices were thus sold in the Victorian period as an alternative to interventionist treatment and the sometimes overly strong medicines prescribed by doctors or sold by unscrupulous traders. Adverts for devices, such as medical belts, appeared in popular lay magazines and the local press, with many catering to a female audience, purporting to cure female ailments (relating to menstruation). Domestic electrical devices also had the added benefit of patients being able to self-administer and control their own treatment.

For example, the Harness Electropathic Belt made by the Medical Battery Company was promoted to restore health ‘without physic’ (i.e. medicine). The proprietor behind the Medical Battery Company was a man called Cornelius B Harness, who used his business to market an array of devices, including electrical suspenders, gymnastic apparatus, electrical hairbrushes and corsets, all purporting to cure a range of diseases and ailments. Harness claimed that his medical belt could treat nervous complaints, indigestion, sleeplessness and impart ‘new life and vigour’.

A medical belt in the Archives

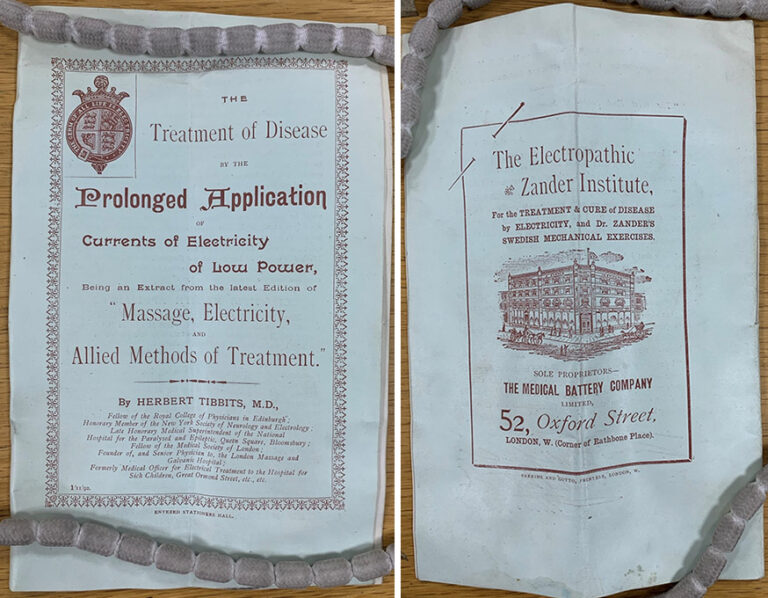

Harness’ promotional material also contained laudatory testimonials from the likes of the medical profession. In fact, one medical practitioner was particularly enamoured with Harness’s business model. Dr Herbert Tibbits was a qualified medical practitioner and a licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians (footnote 2). Tibbits was an advocate for the treatment of disease by electricity, producing literature on his research and founding the London Massage and Galvanic Hospital, as well as acting for a time as the Medical Officer for Electrical Treatment to the Hospital for Sick Children. A pamphlet on ‘The Treatment of Disease by the Prolonged Application of Currents of Electricity of Low Power’ by Tibbits featured an advertisement for the Medical Battery Company and contained testimonials for the company’s products.

Ueyama has explored the conflict between commerce and professional ideals with a case study of Tibbits’s involvement with the Medical Battery Company and the inclusion of his name in advertisements praising the company (footnote 3). Unfortunately for Tibbits the Censor’s Board of the Royal College of Physicians was active in attempting to quash professional interaction with commerce, eventually resulting in an order for his removal from the medical register in December 1894, ‘for unprofessional conduct in associating himself with C B Harness and the Medical Battery Company, and in regard to the London Massage and Galvanic Hospital and West-end School of Massage, Weymouth Street’ (footnote 4).

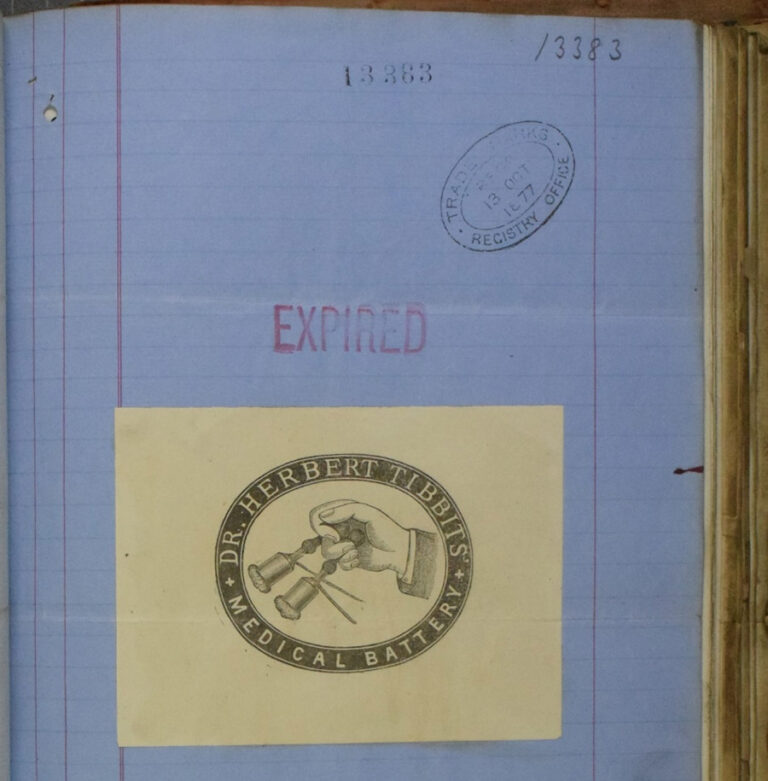

Trademark representations held at The National Archives also show that Tibbits registered ‘Dr. Herbert Tibbits’ Medical Battery‘ as a trademark in December 1877, indicating that he was looking to benefit from electro-therapeutic devices commercially.

This battery theoretically emitted a low electrical current, which could be used on a variety of medical devices, such as medical belts. It can be difficult to ascertain whether the use of these types of devices were efficacious, with the majority of testimonials in the historical record found via the likes of hyperbolic laudatory advertisements. Navy surgeons’ medical journals are one source that can give us insight into the efficacy of medical treatments for a variety of afflictions.

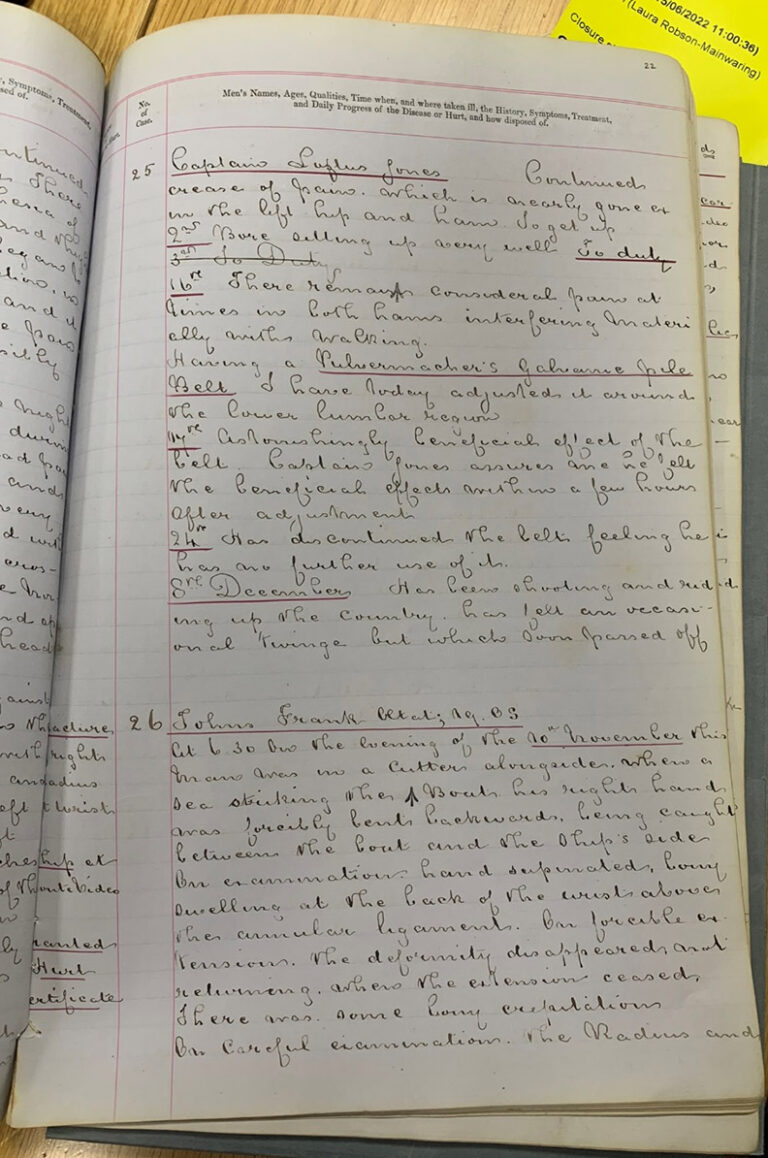

For example, on 28 October 1800 the surgeon on the ship HM Garnet recorded that the Captain, Loftus F Jones, was suffering with sciatica. His ‘agonising pain’ was treated with an injection of morphine, a belladonna plaster, and bed rest. However, it wasn’t until 16December when the ship’s surgeon supplied Jones with Pulvermacher’s Galvanic Pile Belt that he noted the patient’s significant improvement; the effect of the belt was described as ‘astonishingly beneficial’ and just over a week later Jones required it no longer.

However, legal records held at The National Archives show that it’s unlikely that Harness’s Medical Belt, that Tibbits promoted, would have emitted a significant amount of electricity to possess any therapeutic qualities.

In the 1890s the editors of The Electrical Review reported extensively on the charlatan nature of electro-therapeutics, publishing a series of exposés against the Medical Battery Company. They detailed experiments that showed the chemical effect of metals on the skin could only produce a small amount of electricity, thereby not penetrating the skin or giving any therapeutic effect. As part of their frequent exposés they berated Tibbits’ involvement in the company, calling out his professional morals. Tibbits then proceeded to sue the proprietors of the magazine, claiming £5,000 for libel (footnote 5). As part of the libel trial, his pamphlet was used in evidence to show his ignorance of electricity’s effect on the body, and one of Harness’s medical belts was examined by the eminent scientist Lord Kelvin, who was then President of the Royal Society. In his witness testimonial, 11 February 1893, Kelvin noted that ‘This belt, or any other belt constructed to the same pattern is incapable of generating an electric current without additional connecting wires to complete the circuit between the copper and zinc discs, and if worn on the body as it is, it would be electrically ineffective’.

Pleadings from the Queen’s Bench found within J 54/765 show that the defendants ended up winning the case (footnote 6). Astonishingly the belt, used as evidence, still survives within the Queen’s Bench depositions in J 17/283, tucked into an unassuming envelope.

The end of electro-therapeutics?

Despite professional and general mistrust of medical electricity in the period electro-therapeutics continued to flourish on the margins of and even within professional medical practice – such as with electric medical apparatus like consultant room couches (footnote 7). The medical profession’s relationship with electricity would continue to evolve. The early 20th century would see new electro-therapeutic devices come to the medical marketplace and from 1938 electro-convulsive therapy began to be used to treat psychiatric conditions (footnote 8).

Today there are a multitude of domestic electro-therapeutic gadgets available for consumers and electro-therapy – albeit in a developed form – is now considered an important part of many parts of medical practice, particularly within the field of physiotherapy and for managing pain.

Further reading

I Rhys Morus, Shocking Bodies, Life, Death and Electricity in Victorian England (The History Press, 2011). Available in the library: 333.7932 MOR.

A Wexler, The Medical Battery in The United States (1870–1920): Electrotherapy at Home and in the Clinic, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 72: 2 (April 2017), pp.166–192.

T Ueyama, Capital, Profession and Medical Technology: The Electro-Therapeutic Institutes and the Royal College of Physicians, 1888-1922, Medical History (1997), 41, pp. 150-181.

Footnotes

- S Ruston, ‘The science of life and death in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein’, British Library Blog, May 2014.

- Medical Register, 1883, p. 858. UK Medical Registers 1859-1959 are available via Ancestry.

- T Ueyama, Capital, Profession and Medical Technology: The Electro-Therapeutic Institutes and the Royal College of Physicians, 1888-1922, Medical History (1997), 41, pp. 150-181.

- The Chemist and Druggist, 15 December 1894, p. 834. Available via Wellcome Library/Archive.org.

- T Ueyama, Capital, Profession and Medical Technology: The Electro-Therapeutic Institutes and the Royal College of Physicians, 1888-1922, Medical History (1997), 41, pp. 150-181.

- High Court of Justice, Queen’s Bench Division Pleadings, J 54/765, no. 1914, 15-17 February 1893.

- ‘Electric Age: Condenser couch’, Wellcome Collection Blog. June 2017.

- J F Stark, ‘“Recharge My Exhausted Batteries”: Overbeck’s Rejuvenator, Patenting, and Public Medical Consumers, 1924–37’, Medical History, (2014), 58 (4), pp. 498-518.

HMS Garnet journal is dated 1880 not 1800 as stated. Electro-convulsive therapy (otherwise known as ECT) is the abhorrent practice of destroying people’s brains leaving them in a very sorry state for the rest of their lives and which persists today.

I joined the London Ambulance Service in 1975 and for a few years we were still taking patients to hospitals for ECT treat treatment. One patient sticks in my memory as the lady was crying and didn’t want to go. Seems so barbaric now.

Quite an interesting article on the process of electro inventions.

Thank you very much.

I recently came across a letter published in The Times on 26 June 1849 regarding the successful treatment of an 8 year old girl with cholera, using electricity.

“Dr. Peacock applied one pole of the galvanic machine over the heart, the other over the region of the stomach, or rather of the solar plexus (a sort of grand central terminus of the nerves, supplying all the viscera). In half a minute the child began ‘orally, some strong beef tea was got into her stomach in less than ten minutes and ultimately the resurrection was complete.”

Interestingly, the letter was in response to another letter published the day before outlining the argument that epidemics such as cholera were due to a drop in atmospheric electricity.

My grandfather tried a waistband to try to cure him of a mental health difficulty. It interfered with his heart rhythm and died aged 35.

ECT is not as barbaric as it sounds. Sure, in the 1930s it would have been awful, but today with general anaesthetics and muscle relaxants its totally fine. 15 sessions of ECT got me out of a horrible suicidal psychotic depression that no meds would touch. Im now working full time and enjoying life. I literally owe my life to ECT.

Thank you for your real life testimonial Sarah… those who criticise ECT have absolutely no idea how many life ECT has saved. I cannot understand why no legal action is taking against the ‘antipsychiatry’ cult, who are not only defaming the profession, but putting lives at risk.