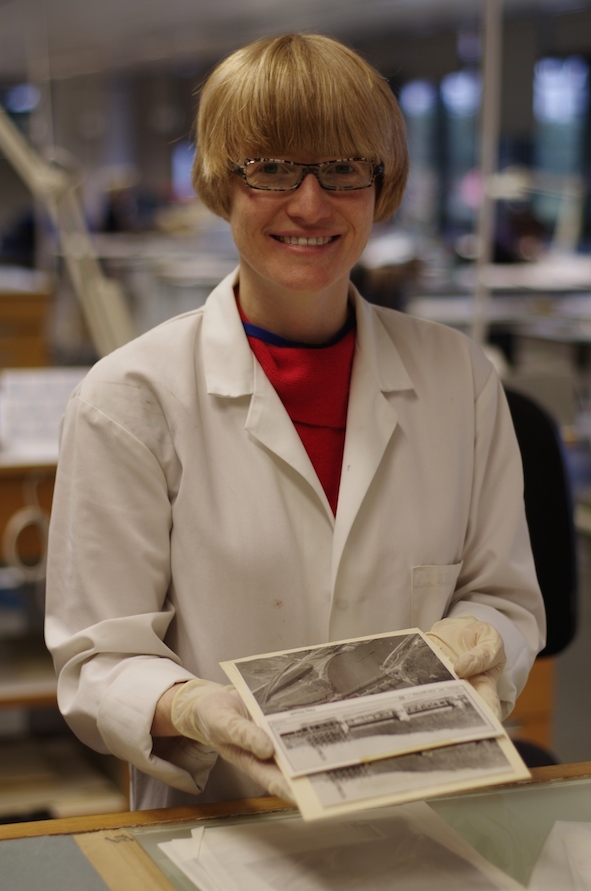

Comparing photographic processes in Collection Care.

Many black and white photographs are prone to silvering (a bluish reflective sheen seen in the shadow areas), yellowing and fading due to the effects of moisture, pollutants and residual processing chemistry. Colour images are prone to light and dark fading.

This blog will give a couple of examples of the types of photographic collections that we hold, discuss how knowledge of photographic process is key to understanding future care needs, and provide some examples of how this information is used.

Photographic collections at The National Archives

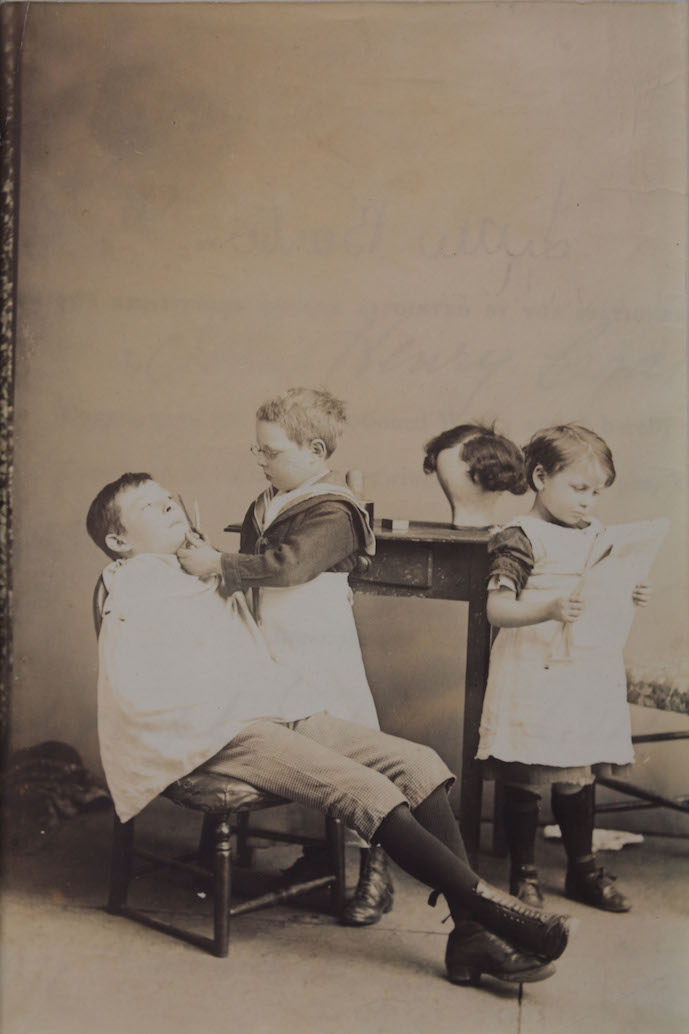

A shave at the barbers (catalogue reference: COPY 1/418/575)

The National Archives’ collection includes approximately eight million photographs. The subjects are varied, and include Victorian and Edwardian photographs from the 1850s; of Eccles cakes, circus performers with boa constrictors, ‘the oldest lady in bed’, children acting out barber shop scenes and the Titanic.

Later collections include the more serious Operation Sandstone, a unique survey of the British coastline which began in 1947 to help NATO forces plan a re-invasion in case the country was taken over by communist forces.

Understanding different photographic processes

Knowledge of photographic processes is vital to understanding their sensitivities and care needs; but identifying these can be challenging and requires experience. Three types of photographs represented in our collection are albumen, silver gelatine and platinum prints.

Albumen prints were popular at the end of the 19th century. The image layer is made of silver particles suspended in albumen, or egg white. A well-known company in Dresden used an average of six million eggs per year in manufacturing the paper. The British Journal of Photography published ‘a hint to albumenizers’, suggesting that egg yolk could also be used to make ‘unrivalled’ cheesecakes. The albumen layer does not respond well to humidity changes, which leads to curling and cracking. For this reason such prints are often mounted, and were more widely used as ‘cartes de visite’. They are also prone to yellowing and fading.

Two ‘cartes de visite’ (albumen photographs from author’s collection)

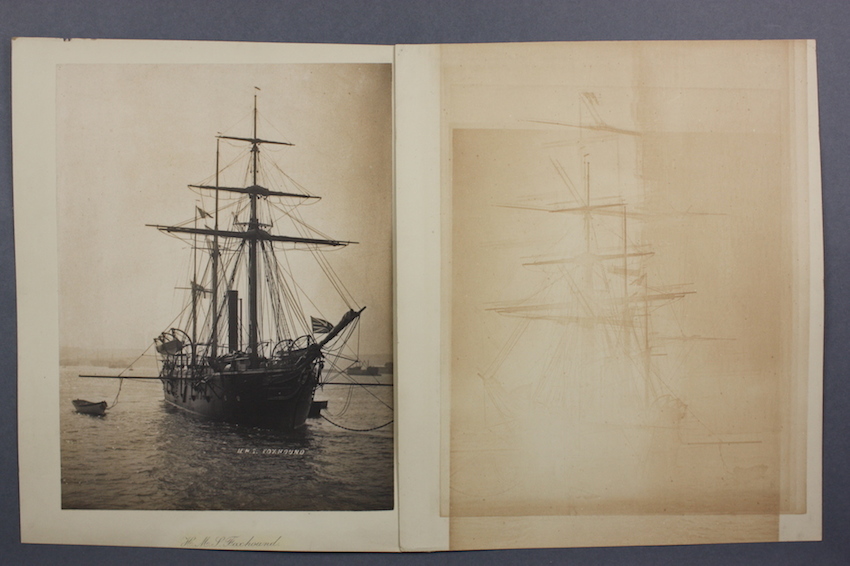

Platinum prints, made of an iron/platinum compound on paper, were patented in 1873. The process became impractical at the outbreak of the First World War as platinum was declared a strategic resource. They don’t fade, but the iron/ platinum compound can cause the paper to become yellowed and acidic, often forming ‘ghost’ images.

A platinum print with corresponding ‘ghosting’ on the back of an adjacent photograph (catalogue reference: ADM 176/279)

Silver gelatine prints were invented in the 1880s and remain popular to this day. High humidity can cause the gelatine layer to become tacky and also increases the risk of yellowing, mirroring and fading. They are more prone to chipping at the edges, and the image layer can be chemically altered by the salts on a person’s hands. That said they are relatively stable if well-processed and stored in a cool, dry environment.

A silver gelatine print with mirroring (catalogue reference: BT 52/1563)

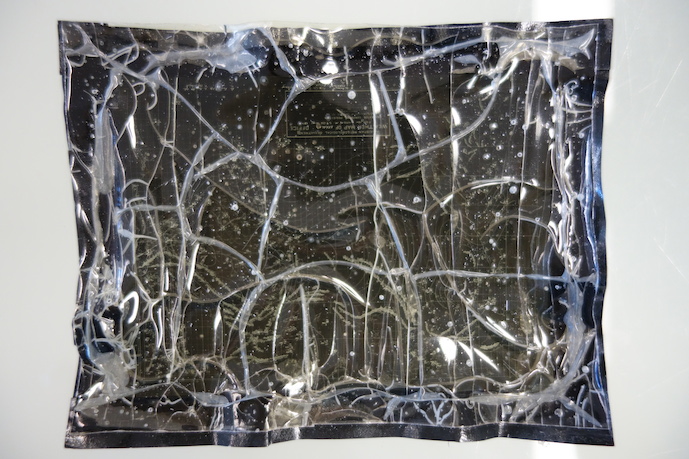

We also have a small film collection which includes microfilm, occasional film strips and sheets, x-rays, slides and colour transparencies. Some of these are on a film support called cellulose acetate, which came into use in the 1920s but can have a life span as short as 60-100 years. The film shrinks, bubbles of acetic acid form and channels develop in the image. The film can be rendered useless unless it is identified and stored in cold or freezing conditions.

A sheet of cellulose acetate film with blisters and channels.

What kind of work does collection care do?

The care of the collection is managed in a variety of ways, including conservation treatment, scientific research, environmental management and advice and guidance.

Conservation treatment

Operation Sandstone photographs that have stuck together.

Conservation treatment can extend the life of our records, minimising the risk of further deterioration as well as making the documents easier to handle and therefore more accessible. Operation Sandstone contains over 40,000 photographs, many of which have been taped together to form panoramas. Adhesive was leeching out, and the photos were sticking to one another and to their glassine bags; in some cases the image layer had already ripped. I investigated techniques for removing the tape and the risks associated with different treatments. These ranged from the use of scalpels to hot air and solvents. Conservation treatment and re-housing were completed over a three year period by a team of conservators and volunteers.

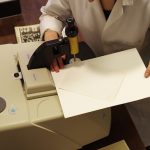

Using scientific techniques

Science allows us to go beyond what the naked eye can see. A technique called Fourier transform infra-red spectroscopy can be used to identify the binding agents used in albumen and silver gelatine photographs. In another process called X-ray fluorescence, a hand-held gun which emits ionising radiation can be used to identify the elements in the photographic image. This can help us distinguish between silver gelatine and platinum photographs, and to identify whether an image has had an additional processing stage and been toned, making it more resistant to pollutants.

- Using Fourier transform infra-red spectroscopy to identify the type of photograph.

- Examining photographs with ultraviolet fluorescence.

Different light sources can be used to understand the deterioration of paper, coatings or additives. Ultraviolet visible (UV) induced fluorescence can be used to identify forgeries, by recognising optical brightening agents which appear very bright in UV light. Optical brighteners were introduced in the 1950s, so couldn’t be present in a 19th century photograph. These and other scientific techniques can be used to understand more about how items were produced historically.

Collection management

The volunteer survey team working in Collection Care.

A survey is currently underway to identify vulnerable materials in our collection, to assess their condition and to address future care needs. This includes photographs, film, photo-reproductive processes and brittle tracing paper.

Gathering information on quantity, process type, housing, condition and subject matter will help us formulate scientific research topics, improve housing, prioritise items for cool storage, plan conservation projects, engage in collaborative research opportunities and investigate less well known subject areas.

The work for the survey was piloted by collection care staff but is now being undertaken by volunteers trained in the identification and deterioration processes of photographs, without whom this project would be impossible.

Plans for the future

The British Film Institute and The National Archives have been exploring opportunities to collaborate on scientific research work that will inform the management of large scale collections. With our conservation scientist Elke Cwiertnia I’m currently investigating a series of black and white and colour film samples for the British Film Institute, who plan to digitise and release more than 500 Victorian films in 2017. We are using science to better understand the materials, address potential conservation issues and enhance our historical understanding.

[…] techadmin on October 14, 2016 Eight million photographs: where to begin?2016-10-14T13:40:53+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

Fascinating insights and must check with the Collections Manager who curates the old photos and film where I volunteer at Winterbourne House to see if they are impacted.

[…] Jacqueline Moon, ‘Eight million photographs: where to begin?’ […]

[…] If you’d like to read more about how we care for the photographic collection at The National Archives, you can read our blog here. […]

[…] Jacqueline Moon, ‘Eight million photographs: where to begin?’ […]