Edward Carpenter (1844-1929) was an extraordinary individual for his time. Carpenter was an author, socialist, free love advocate and early pioneer for gay rights. He spoke openly about topics that were controversial in his lifetime, despite the risk.

This one blog post cannot possibly do justice to Carpenter’s extensive life, his many influences, pursuits and acquaintances; it will focus particularly on what records held by The National Archives can reveal about his life and loves (see footnote 1). Fascinating collections relating to Carpenter can also be found in many other archives, including Sheffield City Archives, the British Library and the University of Manchester Special Collections. Further archive listings can be found in Discovery, our catalogue.

Early life

Edward Carpenter was born in 1844 in Hove in Sussex and studied at Brighton College. He went to university at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, where he was first influenced by Christian Socialist theology.

A turning point for Carpenter was the discovery of the work and poetry of Walt Whitman. They were later to become friends. From this time he began to explore his feelings for other men more. Carpenter wrote to Whitman in May 1889, saying:

‘Because you have, as it were, given me a ground for the love of men I thank you continually in my heart … For you have made men to be not ashamed of the noblest instinct of their nature.’

Edward Carpenter to Walt Whitman, 18 May 1889 (Correspondence) – The Walt Whitman Archive

For a time, Carpenter worked as part of the University Extension movement, which attempted to extend education to people who were otherwise unable to access university learning. Through the movement he met student Albert Ferneyhough, a scythe-maker. He fell in love with Ferneyhough and moved to live with his family – as can be seen in the 1881 Census.

Millthorpe

It was at this time, in 1883, that Carpenter bought his smallholding at Millthorpe, near Sheffield. He moved in, bringing the Ferneyhough family with him. At Millthorpe Carpenter set about modelling a new way of living that focused on a return to nature. While Carpenter had moved to the smallholding for a simpler life, he continued to write and publish extensively. Carpenter wrote on subjects as varied as marriage, prisons and socialism.

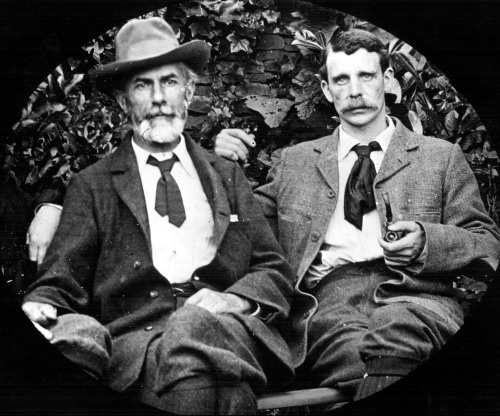

On a train journey in 1891, Carpenter met George Merrill, a working-class man from Sheffield. The two men struck up a deep, life-long relationship, living together at Millthorpe. Their backgrounds were very different: Merrill was 20 years younger than Carpenter and had had a tough working-class upbringing. E M Forster was a friend of the couple and would visit them. The connection between Carpenter and Merrill was thought to be the inspiration for Forster’s novel ‘Maurice’, in which the key characters have a similar relationship dynamic.

Literature

In the 1890s Carpenter first started trying to publish on the topic of homosexuality, which was a huge risk at the time. The Labouchère Amendment in 1885 had extended the criminalisation of sex acts between men, and cases such as the 1889 Cleveland Street Scandal and the 1895 trial of Oscar Wilde cast a shadow over the 1890s.

In 1894 Carpenter published the pamphlet ‘Homogenic Love and Its Place in a Free Society‘ – for private circulation only at first, due to the controversial subject matter. Further works followed, including ‘The Intermediate Sex‘ which was published in 1908. These books took the then controversial stance that gay relationships should not be shameful, referencing a long-standing canon of literature and art that had referenced same-sex desire. These texts argued against the State’s use of repression and censorship of same-sex love.

‘Since no amount of compulsion can ever change the homogenic instinct in a person, where it is innate, the State in trying to effect such a change is only kicking vainly … to cripple and damage a respectable and valuable class of its own citizens.’

Extract from ‘Homogenic Love and its Place in a Free Society’ by Edward Carpenter

Backlash

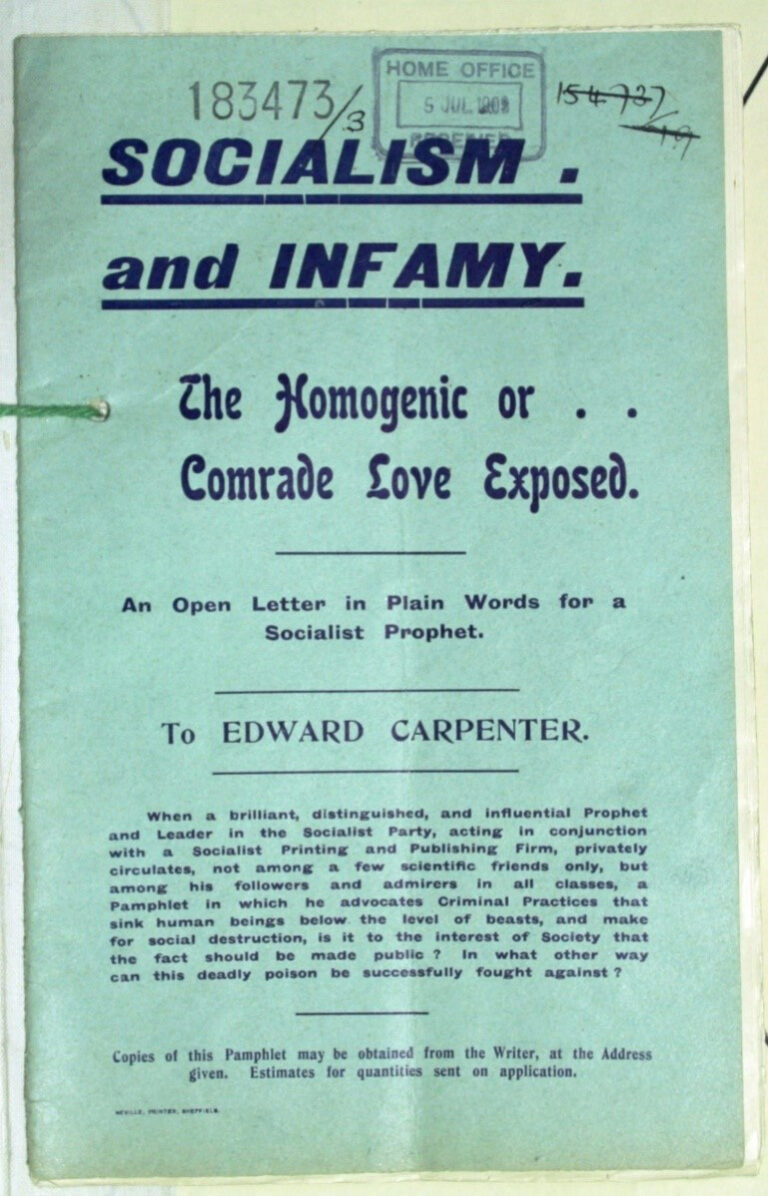

These publications provoked a reaction, prompting complaints to the Home Secretary and Scotland Yard (footnote 2). Our collections contain an outraged pamphlet, written by Mr D O’Brien in 1909 entitled ‘The Homogenic or … Comrade Love Exposed’ (footnote 3). O’Brien, a member of the right-wing Liberty and Property Defence League, instigated his own campaign against Carpenter, which he saw as his ‘painful duty’ – spending over 15 pounds of his own money to print and circulate these pamphlets. He saw homosexuality as ‘doing infinitely more mischief to human society than the greatest criminal’. In his pamphlet and letters to the Home Office, O’Brien accused Carpenter of advocating ‘unnatural vice’ and forming a society which indulged in this ‘vice’ (footnote 4). Sheila Rowbotham notes that Carpenter was ‘rattled and distressed’ by the whole episode (footnote 5).

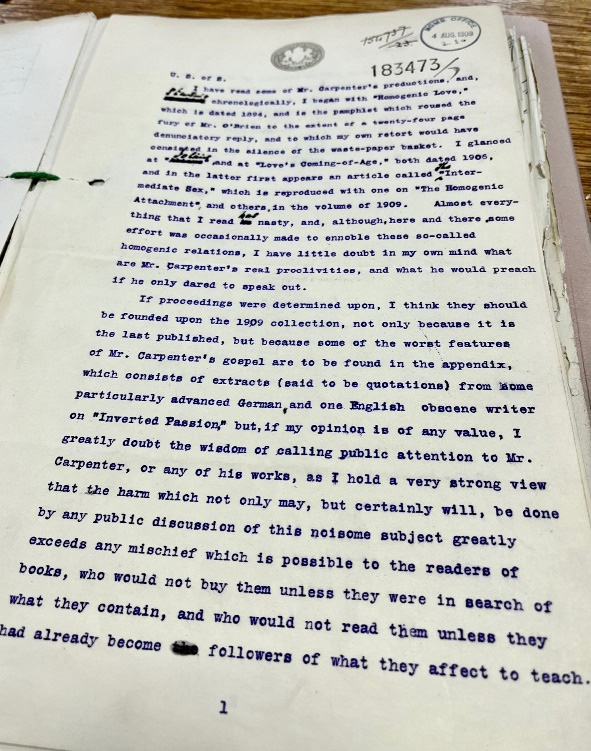

The police investigated, purchasing copies of various works of Carpenter’s including ‘Iolaus’, ‘The Intermediate Sex’ and ‘Loves Coming of Age’. ‘Homogenic Love’ was not purchased due to its availability only through private circulation. Records show a discussion about the merits of prosecuting based on the books’ contents. Charles Willie Mathews, Director of Public Prosecutions, said:

‘I greatly doubt the wisdom of calling public attention to Mr Carpenter, or any of his works, as I hold a very strong view that the harm which not only may, but certainly will, be done by any public discussion of this noisome subject greatly exceeds any mischief which is possible to the readers of books, who would not buy them unless they were in search of what they contain, and who would not read them unless they had already become followers of what they affect to teach.’

HO 144/1043/183473

The banning of Carpenter’s works had been avoided, despite O’Brien’s ardent protestations.

Observations

All this attention led to observations on Carpenter and Merrill by Derbyshire police who were ‘anxious to get a strong case before taking any proceedings’. In O’Brien’s letters were mentioned the contact details of a number of people supposedly willing to provide evidence of Merrill’s sexuality.

When the police approached these individuals, some declined to speak, while others gave no useful information. A number of men mentioned sexual impropriety, although whether this actually happened, or was just used to try to discredit Merrill, is unclear. No incriminating evidence was found against Carpenter ‘beyond strong suspicion’. There was not enough evidence for the police to act. The very fact that publishing such works and living together was enough to draw police attention shows the risks these men were taking in just living their lives.

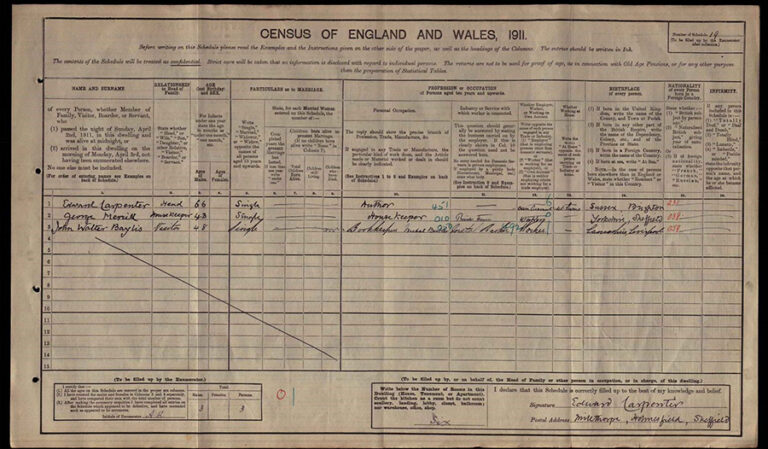

The next mention of Carpenter and Merrill in our records comes not long afterwards, in the 1911 Census. Both men were listed as single, although living together, with Merrill also listed as the ‘housekeeper’. By this time Carpenter was becoming involved in other organisations. He worked as part of the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology, which was founded in 1913, with a particular focus on homosexuality.

A further reference to them follows in the 1921 Census – where the couple continued to live together and evade the law. Shortly afterwards, in 1922, they moved to Gilford, Surrey. Ultimately, Carpenter and Merrill were partners for almost 40 years.

Merrill died in 1928 from complications linked to alcoholism, with Carpenter dying the following year. The pair were buried together at the Mount Cemetery, Surrey.

Carpenter actively lived the life he wrote about – fighting for equality, liberty and socialism throughout.

Find out more about the LGBTQ+ history in our collection through our Pride Portraits project, LGBTQ+ History podcast episode and our research guide to Sexuality and Gender Identity.

Footnotes

- ‘Edward Carpenter: A Life of Liberty and Love’ by Sheila Rowbotham is a great source on the life of Carpenter.

- From this point on the blog is mainly based the Home Office papers on indecent publications in HO 144/1043/183473, 1909-1910.

- Carpenter used the term ‘homogenic’ in his text – this word derived from the Greek homos meaning ‘same’ and genos meaning ‘sex’. He also used the phrase ‘Comrade Love’ to refer to same sex desire.

- Carpenter could have tried to sue O’Brien for libel based on these accusations – but the Wilde trials showed this was not a wise move. A libel trial based on proving or disproving homosexuality could turn into criminal charges. In Wilde’s case it led to a trial and imprisonment.

- ‘Edward Carpenter’, Rowbotham (London, 2009), p. 286.

An excellent article on a pioneer in LGBT rights and well worth including on your emailing

Thanks indeed

Whilst I acknowledge that this article states that it is based solely on archives at TNA, it is very disappointing that nowhere does it make reference to the huge Carpenter Archive held at Sheffield Archives. As a former City Archivist of Sheffield I find this article sadly lacking a fundamental reference point.

Perhaps worth mentioning that the Edward Carpenter collection is at the City Archives/Libraries in Sheffield – this is only a part of the story and without reference to the main collection in Sheffield, researchers may not realise there’s A LOT more information out there aside from what’s buried in these records in London. Also – Millthorpe is in Holmesfield (not Holmerfield) which is in Derbyshire not Sheffield.

Interesting article thanks.

Gosh… Basically, they’ve could’ve been indicted, arrested, separated, or worse, imprisoned (for Merrill). They were in fact so close to all these disasters yet they evaded them all—by luck, by fate, or by human logic we don’t know, but I’m certain it’s a combination of all three. It’s almost like they were meant to have a happy ending and last each other’s whole life despite all the odds working against them. Yet they prevailed in the end.

Not to mention, these investigations and scrutiny against them happened before 1913—before E.M. Forster had visited them in their home and got inspired so much that he had to write Maurice, a gay romance novel with a happy ending. That is to say, had Edward and George been torn apart, Forster would’ve likely never seen them together and Maurice would’ve never happened.

It must be their fate then, to be together for a lifetime and become the genesis of inspiration for Maurice and its happy ending.

@mav liv

Interesting premise… I have ‘Maurice’ on my bookshelf. Definitely puts the whole history of the book in a different light!

reminds me of the Butterfly Effect