We are frequently told that history does not repeat itself, but for the historically minded it is surprising how often you find echoes of the past in current events. Nowhere has this been more apparent to me than the recent Greek finance crisis. Unsustainable long term loans; a troika of foreign creditors, disagreements between the other European powers and bitter internal politics: all of this sounded awfully familiar.

To find out more I ordered up some records relating to the Greek debt crisis of 1898 and the International Finance Commission (IFC), which was formed to manage the new loans which propped the country up.

Greece in the 19th century had a rather unhappy time with regard to its fiscal situation. The country emerged from its war of independence in 1832 with large debts to British and French banks, which were consolidated in 1833 into loans guaranteed by the British, French and Russian governments.

Due to economic difficulties, Greece defaulted on these loans in 1843 and 1860, and each time came to an agreement with its creditors about how to restructure the debt.

In 1893, following a period of relative stability, a collapse in the price of currants – Greece’s largest export – put the economy in a tail spin once again. At the end of the year the Greek government was forced to tell its creditors that they was unable to make payments on the plethora of loans. In December the British Minister at Athens reported on a conversation with the Greek Prime Minister in which he was told that ‘as Greece was now bankrupt, she must negotiate directly and honourably with her creditors’.[ref] 1.Mowatt to the Foreign Office, 22 Dec 1893, catalogue reference: FO 32/658[/ref]

Despite this honest statement, Greece was unable to come to an agreement with foreign creditors. The situation got worse in 1897 when war broke out between Greece and the Ottoman Empire. The war proved disastrous: Ottoman forces were better trained and equipped than their Greek opponents. Greece was forced to accept a humiliating peace in which it was supposed to pay out a large amount of money in an indemnity. Given the state of Greek finances this was impossible and no one was willing to lend money given the recent default.

Not willing to let Greece fall apart, the European powers began to discuss how best to support the country and provide the funds required. This was by no means a selfless move. Greece still owed huge amounts of money to both foreign governments and foreign banks, and they wanted to make sure they would still get this back. Initial discussions on providing a general European guarantee of Greek debts in return for certain controls ran into difficulties. As Sir Frank Lascelles, the British Ambassador in Berlin, pointed out:

‘that such an European guarantee should be given, however, is out of the question; because even in the improbable event that several European Powers would be prepared to agree to it, Germany would certainly refuse under any circumstances to undertake a financial guarantee for Greece.’[ref] 2. Lascelles to Salisbury, 23 September 1897, catalogue reference: FO 32/699[/ref]

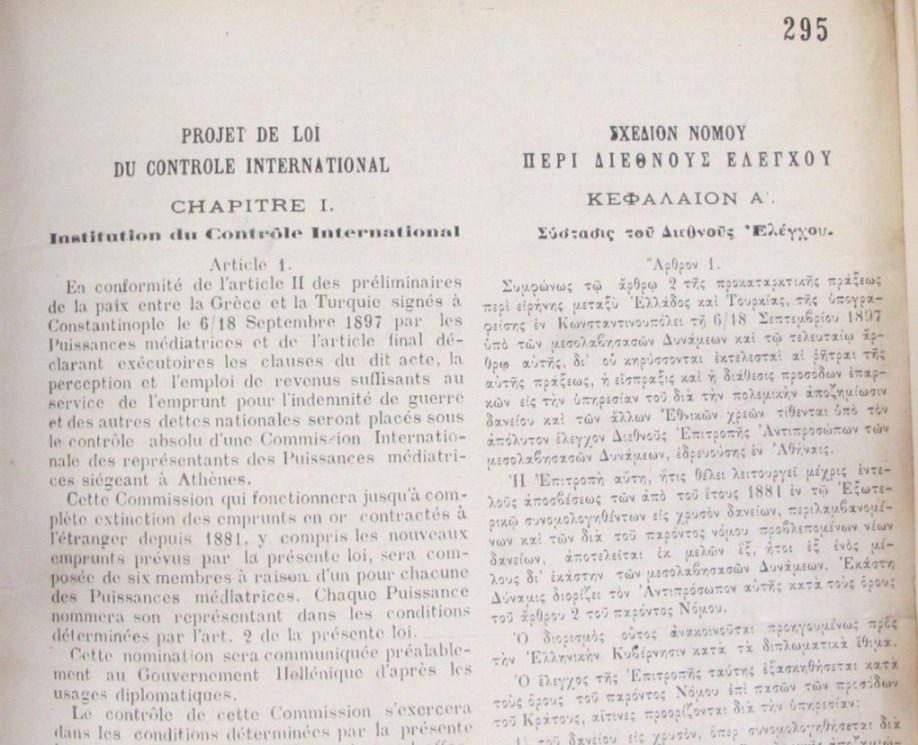

Eventually the Germans accepted the need for a unified approach and a group of delegates from the six major European powers – Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Russia – met in Athens to study the Greek financial situation. They recommended that a body be formed to monitor the situation and protect the interests of Greece’s international creditors. This body, called the International Finance Commission (IFC) was to have the power to administer Greek finances and overrule the Greek government where necessary in order to protect the interests of the other European powers. This was to be written into Greek law. The British delegate, Major Law, noted that the:

‘necessity of great delicacy of treatment in order to obtain a maximum of security with a minimum of apparent interference with the ordinary administration of the country rendered the task of drafting the law a very difficult one.'[ref] 3. Major Law to Egerton 20 Jan 1898, catalogue reference: FO 32/708[/ref]

The precise terms of the new loans to Greece and agreements made with previous bondholders proved equally difficult, with Germany once again holding out for the most stringent of terms. Bernhard von Bülow told a Budgetary Committee in Berlin that:

‘the German government was fighting not only for the interests of its own nationals but for all foreign creditors and of the great principles of good faith and honesty in public life. He cherished the hope that the Greek Government would realise the great benefits that would accrue to the country from financial control.’[ref] 4. National Zeitung, 24 Jan 1898, catalogue reference: FO 32/708 [/ref]

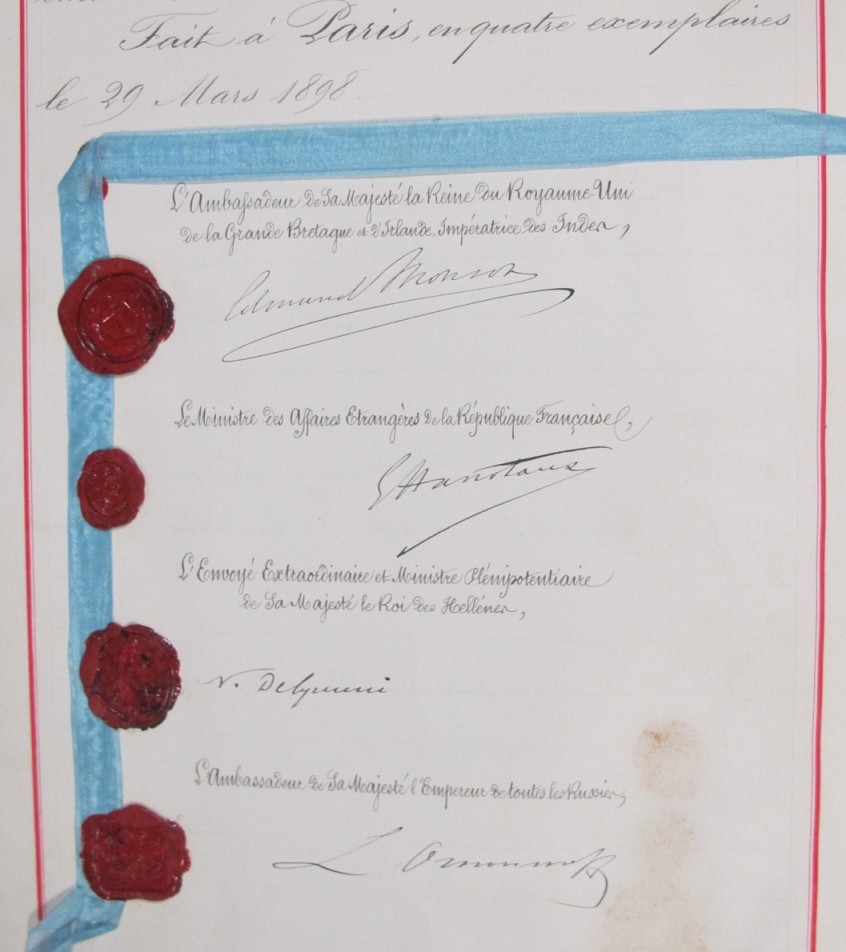

The terms were eventually agreed and the IFC was established in spring of 1898. At the same time, the Greeks raised a new loan to pay off their indemnity to the Ottomans.

Agreement to guarantee the Greek debt signed by representatives from Britain France, Greece and Russia (catalogue reference: FO 93/38/18)

The IFC proved very effective in ensuring Greece’s creditors were paid in accordance with the agreements drawn up in 1898. German and Austrian membership of the Commission lapsed following their defeat in the First World War, while the Greek government refused to let a Soviet delegate replace the old Tsarist official in 1920, so membership was reduced to three.[ref] 5. (T 160/778)[/ref] The interwar years were ones of extraordinary political instability in Greece, but the IFC remained successful in ensuring that Greece paid its debts throughout the turbulent 1920s and helped build a modern tax structure. Despite this the IFC was unable to prevent a new default in 1932 when the global economic depression struck the country.

Although the IFC had become effectively redundant by the end of the 1930s, abolishing it proved even more difficult than establishing it. The British Foreign Office began to take the matter seriously in the 1960s, but administrative irregularities continued to create problems.[ref] 6. Mallaby minute 2 June 1965, catalogue reference: FO 371/180019[/ref] By 1972 a Treasury official minuted that:

‘For some time, the IFC prevented excessive expenditure by the Greeks, and supervised the servicing of their debts. But it has not performed these functions since 1937; indeed all it has done since then is pay its own staff! The politest thing that can be said of the efforts of most of the other parties concerned in the meantime is that they have considered the matter at a correspondingly leisurely pace: I cannot exempt myself from this.’[ref] 7. Palmer to Roberts 25 Feb 1972, catalogue reference: T 354/436[/ref]

The British government asked their French colleagues for their views on the matter and failed to receive a response for over a year. As one British official noted this was ‘fully in keeping with the leisurely fashion in which this appalling and obscure subject has been handled’.[ref] 8. Prendergast to Partridge. 15 May 1973, catalogue reference: T 354/436[/ref] This procrastination continued for some time, and an agreement to abolish the IFC was only reached in 1975.

The history of the IFC has, unsurprisingly, been almost entirely forgotten, but the remarkable echoes of the past which can be seen in the events in Greece this year suggest that we should look more closely in the obscure corners of our past.