The little-known records of the High Court of Admiralty (HCA) provide vivid details of overseas exchange and European colonialism between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries. They include thousands of letters in many languages, the personal archives of merchants and seafarers, artifacts such as jewellery and textiles, as well as papers from the transatlantic slave trade.

As part of The National Archives’ ongoing efforts to improve access to HCA, Bethan Davies, a PhD candidate at the University of Roehampton, undertook a four-month placement working with us. During this time, Bethan found previously unknown documents that speak to her research into the cultural and material history of sugar in the early modern period. Her blog below focuses on a curious recipe for marshmallow syrup, which Bethan has brought to life through a broad and surprising range of techniques (including her own culinary skills!). It shows how a simple recipe can teach us so much about the role of sugar in English society and in the country’s early colonial expansion.

– Oliver Finnegan, Prize Papers Records Specialist, The National Archives

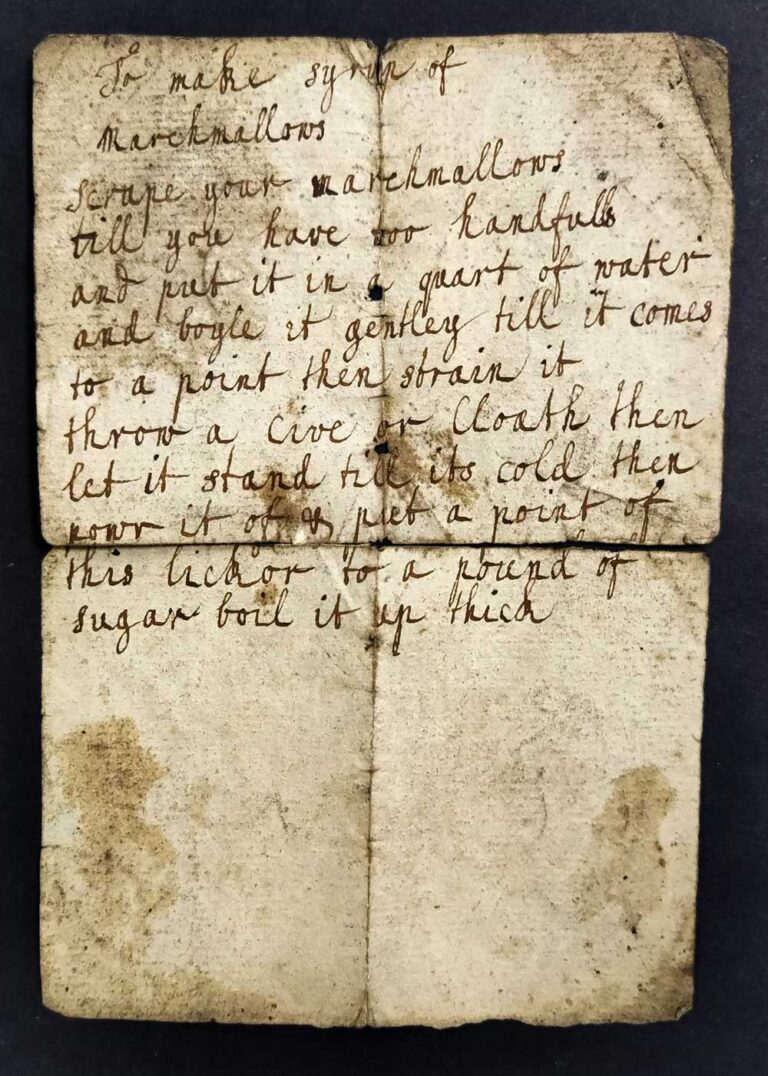

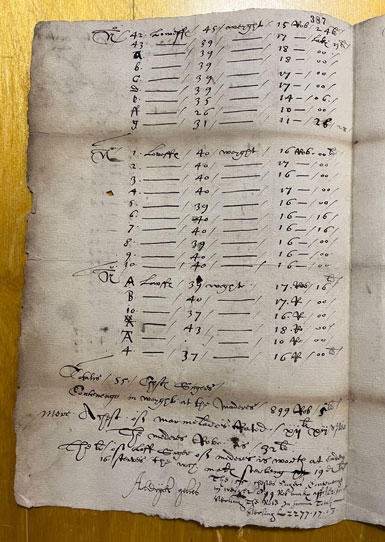

The unexplored miscellanea of the High Court of Admiralty records seems an unlikely place to find a recipe. Nestled amongst a collection of account books that were likely used as exhibits during a legal case involving the ship The Abraham of London (circa 1633–1637) is this recipe ‘to make syrup of marchmallows [marshmallows]’.

Marshmallow as medicine

Marshmallow syrup was commonly used in early modern England as an herbal panacea, easing stomach pains, coughs, colds, and rheumatism. The recipe calls for marshmallow plant, a white flower indigenous to Europe and North Africa. The plant’s virtues were praised in contemporary herbals and receipt books in both manuscript and print form. This recipe, written in a neat and legible hand, instructs the reader to boil the marshmallow plant in water, strain the liquor through a sieve, and then boil it with a pound of sugar to form a sweet and sticky syrup.

Hugh Plat’s 1607 broadside ‘Certain Philosophical Preparations of Food and Beverage for Sea-Men, in their Long Voyages’ advocates the mariner’s use of such ‘essences of spices and flowers…incorporated with syrups’ as approved medicines and antidotes for ailments arising at sea. Plat is aware of the value of sugar in such remedies, which makes the syrups ‘more pleasing to nature’ and ‘more familiarly taken’.

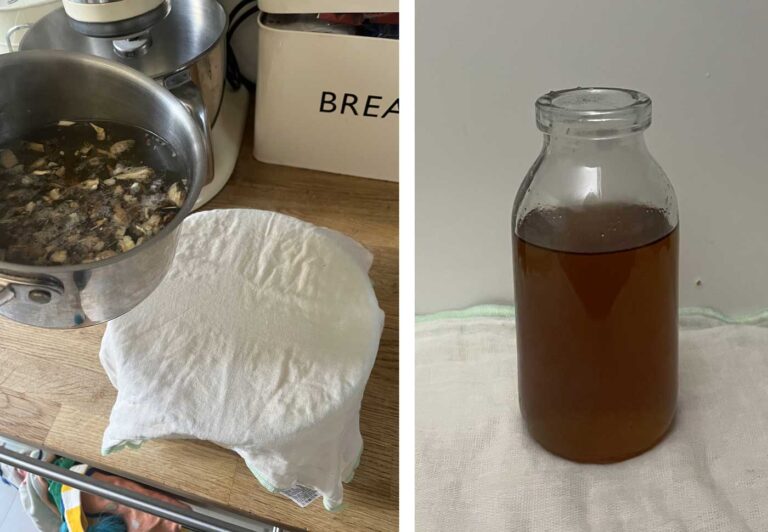

Using methods from culinary practice-as-research, I recreated the marshmallow recipe in my own kitchen, and can verify that the prodigious inclusion of a pound of sugar certainly helped the medicine go down! The sugar masked the overpowering woody and musky flavours of the marshmallow flower.

While the recipe is located within a box of administrative records that discuss Anglo-Dutch trade in Barbados in the 1620s–1630s, the provenance of the marshmallow plant suggests that the recipe is not likely to be directly connected to the Caribbean island.

Perhaps the recipe was a personal possession of Andrew Hardie, captain of The Abraham of London, and resident of Shadwell, or of Richard Pargiter, a merchant resident in London (Hardie’s and Pargiter’s papers are mixed together in HCA 30/636). As the hand of the recipe does not match any other documents in the box, it is conceivable that the recipe was written by a female member of one of the mariners’ family and given to them before they began their voyage.

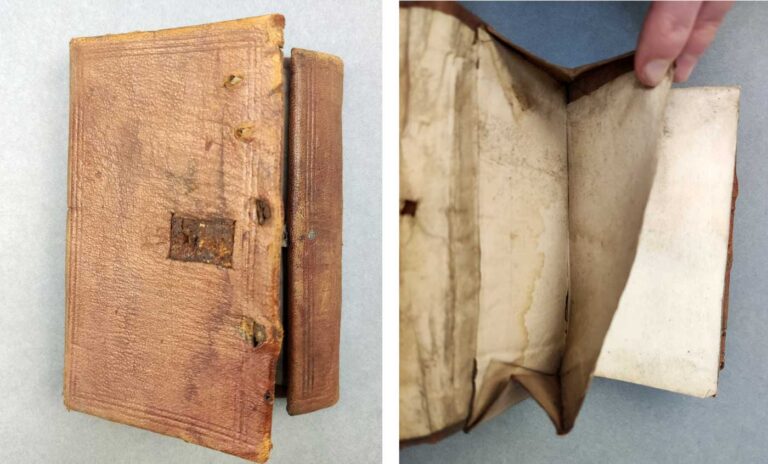

The recipe’s small size and marked fold lines suggests that it was stored folded into a rectangle, and likely tucked into a pocket of a sailor’s wallet for safekeeping. Leather wallets that sailors owned were often made in the form pictured above and had an interior pocket for storing precious or useful documents.

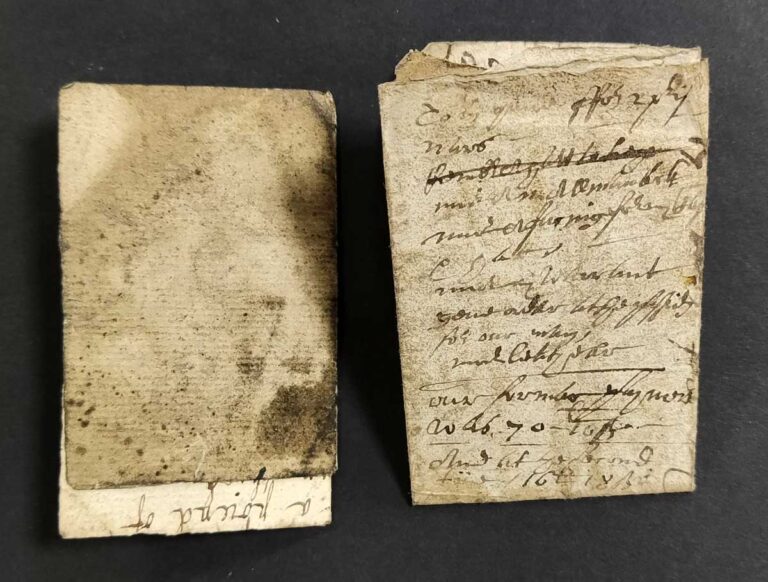

Another sheet in the same collection is identical in size to the recipe and show the same fold lines, so was also probably folded and stored in the same sailor’s wallet, which includes a handwritten prayer on one side of the document. It seems that both the recipe and prayer were treasured possessions on board a potentially treacherous voyage, both used in markedly different ways to preserve bodily and spiritual health respectively.

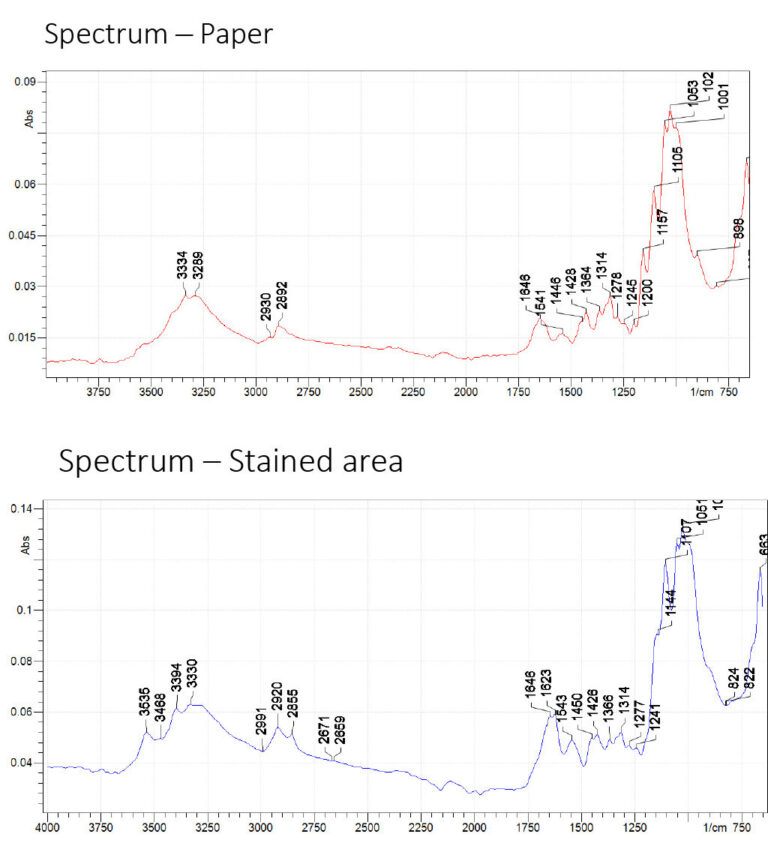

The heavy stains, finger marks, and pronounced fold lines point to the recipe’s significant and sustained use. With the help of Lora Angelova, Head of Conservation Research at the National Archives, the recipe’s stains were tested using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR). The FTIR spectrum results revealed that the stains are oil/fat residues. This could be cooking oil, lamp oil, butter, tallow, or even whale oil.

This plethora of possibilities suggest that the recipe was plausibly used at sea within a busy culinary environment, lain open on a dirty workbench and pored over as the instructions were followed.

Consumption and exploitation

The marshmallow recipe’s reliance on a significant quantity of sugar gestures to a larger paradigmatic change in sugar consumption in England in the early seventeenth century.

In the medieval period, sugar had been used in small quantities as a spice akin to nutmeg or ginger, as a preservative to stop food rotting, and as a miraculous medicine. By the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods, however, the commodity was increasingly used as a decorative foodstuff and tasty sweetener displayed and consumed at a ‘banquet’, a post-prandial private ritual of sugar sculptures, sweetmeats, conserves, syrups and gingerbread. These displays required vast quantities of sugar. The sweet banquet had historically functioned as an elaborate act of elite self-fashioning in a display of wealth, prestige, and royal power since the reign of Henry VIII.

By the end of the sixteenth century, this dining ritual had been appropriated by the upwardly mobile members of the mercantile classes. English recipe books targeted at female readers experienced a publication vogue between 1575–1650. The same Hugh Plat who advocated the use of medicinal sugar syrups onboard ship also wrote recipe books. Delights for Ladies (1602) and A Closet for Ladies and Gentlewomen (1608) provided women with culinary and medicinal knowledge which had previously circulated primarily within elite circles.

In 1596, Plat proclaimed that ‘in these days there is nothing accounted either dainty or delicate’ without a ‘due proportion of sugar’. The amount of sugar being imported into London more than tripled between the 1560s and the 1620s. It only became more accessible thereafter, as its supply grew during the seventeenth century, and its price fell by over 56%.

Around 1600, the English demand for sugar was largely satisfied by the Brazilian engenhos [sugar-producing estates] controlled by Spanish and Portuguese landholders. Sugar was harvested in Brazil from as early as 1516, and by the end of the century it had overtaken all competitors, including the Mediterranean islands of Crete and Cyprus, the Maghreb, and the Portuguese and Spanish Atlantic Islands.

The Brazilian sugar industry was reliant on the exploitation of indigenous groups such as the Tupí as well as African enslaved peoples, whose presence in Brazil can be dated to 1520. Sugar, as a temperamental and labour-intensive crop, required a large labour force to harvest it, and increasing numbers of African people were transported across the Atlantic to supply the engenhos that were growing in Bahia and Pernambuco. The decision to transport African captives to Brazil was driven by the continuing resistance of indigenous peoples to enslavement, and Africans continued this resistance against large-scale coerced labour as their numbers increased across the sixteenth century.

The recipe for marshmallow syrup in HCA30/636, and saccharine recipe culture in this period more broadly, index England’s growing participation and culpability within developing colonial economies.

The value of sugar

Further records in HCA 30 attest to the importance of sugar as a prized commodity in early modern England.

Sugar was commonly seized from enemy ships during the Anglo-Spanish war (1585–1604) and we see evidence of this in High Court of Admiralty records.

The intricacies of an Anglo-Spanish Prize case (HCA 30/840/165-171) involving the English privateer John Hawkins, son of the famous slave trader who went by the same name, details the capture of a Dutch ship called The Neptune. The ship was carrying Spanish goods including 55 crates of Brazilian sugar, goods totalling approximately £390,989 in today’s money.

Through many privateering ventures in the 1590s, the English seized vast quantities of slave-produced Brazilian sugar, increasing both the availability and affordability of the commodity in grocers and apothecaries’ shops in London and elsewhere in the country. In turn this meant that sugar was increasingly appearing in the spice closets and still rooms of mercantile and middling women who made confectionary and medicinal syrups in their own homes.

In the centuries to follow, the English nation would become increasingly defined by its sweet tooth. Early High Court of Admiralty records often contain untold stories of overseas trade, colonialism, prize taking and piracy, such as how sugar first came to England’s shores. They can help us trace early sugar usage on land and at sea and ask us to think about the often-tangled path that this commodity, grown under exploitative labour systems, took, leading to consumption patterns that became embedded in English culture.

With thanks to Dr Amanda Bevan, Head of Legal Records, and Dr Lora Angelova, Head of Conservation Research and Audience Development.

Bethan Davies is a PhD candidate in English Literature at the University of Roehampton. Her doctoral research focuses on sugar, sweetness and the cultural construction of femininity in early modern England circa 1590–1642, covering the commodity’s impact on the early modern imaginary. Bethan is also a qualified secondary school teacher and has prepared lessons for The National Archives on the histories of sugar and tobacco in England. She is on Twitter at @bethanmdavies1.

In reading your informative article, I came across the term “saccharine recipe culture”. I tried to find a meaning for that phrase but only found articles on artificial sweeteners. What does that expression refer to?

Thank you.

Since the mid-seventeenth century, the term ’saccharine’ has meant ‘pertaining to or of the nature of sugar; characteristic of sugar; sugary’ (definition from the Oxford English dictionary). Only more recently have people come to associate it with the extreme sweetness of the zero-calorie artificial sweetener named saccharin/ sodium saccharin, which was first discovered only in 1879.

This amount of sugar would lead to rotten teeth amongst the general population. I would add that it is British not just English culture.

This blog focuses on English consumption specifically due to the provenance and nature of the archival and printed sources in the blog. Of course, sugar was affecting consumption patterns in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales as well. It is also worth being mindful that ‘Britain’ in the time period under discussion- pre 1707 and the Acts of Union between Scotland and England- was a labile concept.

Teeth rotted then, just as they do today! Most of us consume much more sugar now than even the wealthy did then.

As for the English/British question, this article is based on evidence from England. It might not be a big step to extend the conclusions to the whole of Britain, but the evidence does not say so.

Thank you for such an informative article. I hope researchers will continue to delve into records which have had little investigation so they may be shared with the public. Who knows what other treasures are yet to be discovered.

What a fascinating article. Thank you Bethan.

great article, I have been looking at the Southampton Records – a big privateering centre in late 16th century plenty of sugar (sugar loaves) and ginger coming in and stored in the large surviving medieval warehouses once used for wool. Local merchants were early in colonising in Barbados and later in the 18th century there was a sugar house to refine sugar in the town in the 18th century. wanting to find out more about the anti-saccharine movement which I understand was led in some respects by children. Poor teeth hygiene was a major killer in the same period of course. bw

Bethan

It’s lovely to see how far you have been able to take this research since we first talked about folding patterns – I’m especially impressed by the prayer and the stains, and what an intimate view set against a much wider context.

The papers from the Abraham are so interesting – and offer a view into the uncatalogued riches of the HCA instance court papers for life at sea, on land, and across the world.

The history of sugar consumption in England is a fascinating journey that intertwines syrups and ships. During the early days, the arrival of ships laden with precious cargoes of sugar was met with great anticipation and excitement. Syrups, crafted from this golden delight, quickly found their way into the cups and kitchens of the English populace.

These sweet elixirs became a symbol of affluence and indulgence, with their consumption reflecting the changing tastes and desires of society. As sugar became more accessible, its demand soared, transforming it from a luxury item to an everyday ingredient. The English, known for their love of tea, soon discovered the blissful marriage of sugar and their favorite beverage.

What a great article. I found it as a result of reading The Good Housewife’s Jewel Thomas Dawson 1596. Surprised by the number of recipes including sugar as a commonplace ingredient (a little earlier than I had thought sugar was quite so common in England) I did some digging and came across your work. Thank you.