In the second half of the 19th century, photography began to flourish in many areas of the world, including India. New photographic societies were established and amateur and professional photographers, both Indian and British, began to expand their activities and set up photographic studios.

With the 1862 Fine Arts Copyright Act, photographers and studios were able to secure copyright protection for their photographs in the United Kingdom. Photographers working in India took advantage of this opportunity, particularly when they intended to sell photographs abroad. The copyright records we hold at The National Archives therefore provide us with a small window into the photographic industries flourishing in India in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

Marking South Asian Heritage month, this blog explores how commercial photography took off in India in the 19th century and highlights photographers appearing in the copyright collection who were part of this story.

The growth of photography in India

The rapidly expanding city of Mumbai (then known as Bombay) became the centre of the Indian photographic industry. The Bombay Photographic Society was established in October 1854 only a year after the Photographic Society of London. It had more than 200 members in the first year and a monthly journal was set up to circulate and exchange photographic expertise.

The membership of both the Bombay and London societies tended to be drawn from the educated and leisured classes, partly due to the expensive and time-consuming nature of photographic processes at the time. For the Bombay Photographic Society, this meant that the membership consisted mainly of ‘gentlemen amateurs’ and civil servants in the colonial government. However, commercial photographers were included in the membership and the Society’s journal provides evidence that there were contributions from Indian members as well as British (see footnote 1).

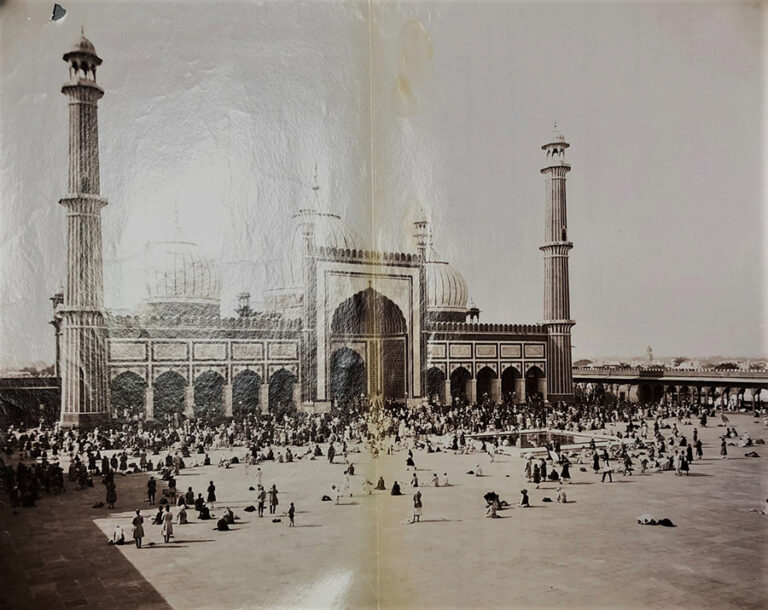

By the 1870s, the commercial photographic industry in Mumbai was flourishing and photographers captured an increasingly broad range of subjects as the 19th century continued. Many photographed landscapes, architecture, culturally and religiously significant objects and scenes of trade and industry.

Photographers also worked to meet the demand for souvenirs from visitors from Europe and elsewhere, primarily in the form of picture postcards, and there are many examples of these in the copyright collection.

Photographic portraiture was also increasingly popular, with specialist portrait studios popping up all over Mumbai and other cities, catering to individuals and families who wished to possess their own photographic likeness.

Celebrated Indian photographers working during this period include Lala Deen Dayal, who received a variety of commissions to photograph events and architecture. He worked as a court photographer in the Princely states of India and in 1897 was appointed photographer to Queen Victoria. Unfortunately, none of his photographs were registered for copyright protection in Britain and so do not appear in the copyright collection.

Photography and imperialism

The expansion of photography in India was heavily influenced by the imperialist aims of the East India Company and the British government. From its earliest development, photography was seen as a tool for documentation and control, particularly in the field of ethnography – the systematic study of human cultures. The British were expanding their control of India in the mid-19th century through both political and military means until direct rule of India began in 1858. Photography was one of the tools that government officials used to document and control India. It enabled British officials to record and share the varying traditions, cultures and environments of the peoples they ruled. To this end the East India Company encouraged the establishment of photographic training centres in Mumbai (footnote 2). However, in the wider context of British imperial control, photography was a complex form of cultural encounter. Indian people were also simultaneously exploring the potential of this new visual technology, and this complexity is evidenced in our records.

William J Johnson was a key figure in early colonialist photography. He travelled to India in the 1840s and established a photographic studio in Mumbai. There are 51 of his photographs registered for copyright protection between 1863 and 1865. Johnson served as secretary to the Bombay Photographic Society and edited its journal. He also contributed heavily to the Indian Amateur’s Photographic Album, which was published by the Society in a total of 36 issues between 1856 and 1859 (footnote 3). The Album was the first photographically illustrated publication of its kind in India (footnote 4) and included ethnographic portraits, landscapes and architectural views, all taken in and around the city of Mumbai.

The work of William J Johnson and the photographs in the Indian Amateur’s Photographic Album and similar publications were intended to create a visual record of the colonial experience and reflect the British imperialist viewpoint (footnote 5). Their ethnographic portraits are usually anonymous, focusing on representing groups or ‘types’ of people rather than individuality, usually the focus of portraiture (footnote 6). Diva Gujral and Nathaniel Gaskell argue that these kinds of images reveal a lack of ‘concern with the sitters as people but rather positioning them as an ethnic “type”, devoid of individualism and personality beyond their role in reinforcing the stereotype’ (footnote 7).

These kinds of images form part of a wider movement in the British Empire to document places which fell under colonial rule through photography. It is therefore important to understand that a great deal of photographs taken in India in this period were taken by the British for a British audience and so reflected their imperialist point of view.

Commercial photographic studios

While the imperialist viewpoint is present across the photographic industry in India in this period, a wide range of people were still involved in this industry and commercial studios were being established all over the country. Some individuals and businesses chose to register some of their photographs with the Stationers’ Company for copyright protection. It is likely that those photographs which were registered in this way were thought to be of particular commercial value. Below are some of the photographers whose photographs can be found in the records.

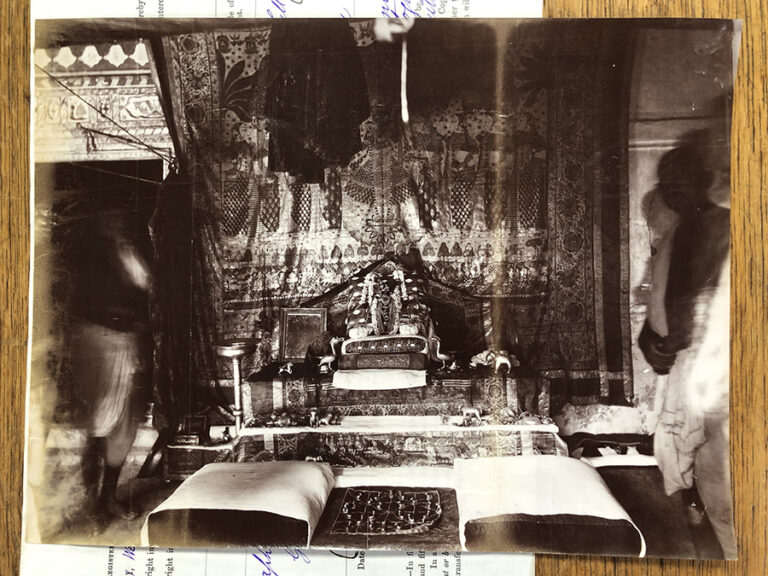

Chunni Lall & Co.

Chunni Lall ran a commercial photographic studio based in Mathura called Chunni Lall & Co. and registered one photograph for copyright protection in 1891. Chunni Lall’s commercial photographic studio was employed by Frederic S Growse, a British civil servant of the Indian Civil Service, to illustrate his book Mathura: A District Memoir published in 1874. The book was written as a guide to the district of Mathura for new district officers, and included explorations languages, history and the origins of place names (footnote 8).

Govind Shriniwas Welling

Govind Shriniwas Welling registered 65 photographs for copyright protection with the Stationers’ Company, all registered together on 17 September 1909. They are all examples of picture postcards presenting photographic portraits of unnamed individuals.

When submitting the photographs for registration, he recorded himself as ‘proprietor of S. Mahadeo & Son, 85 Church Street, Belgaum, India’ (footnote 9). This business was named after his father, Srinivas Mahadeo Welling, who had first set up as an independent professional photographer in the 1850s.

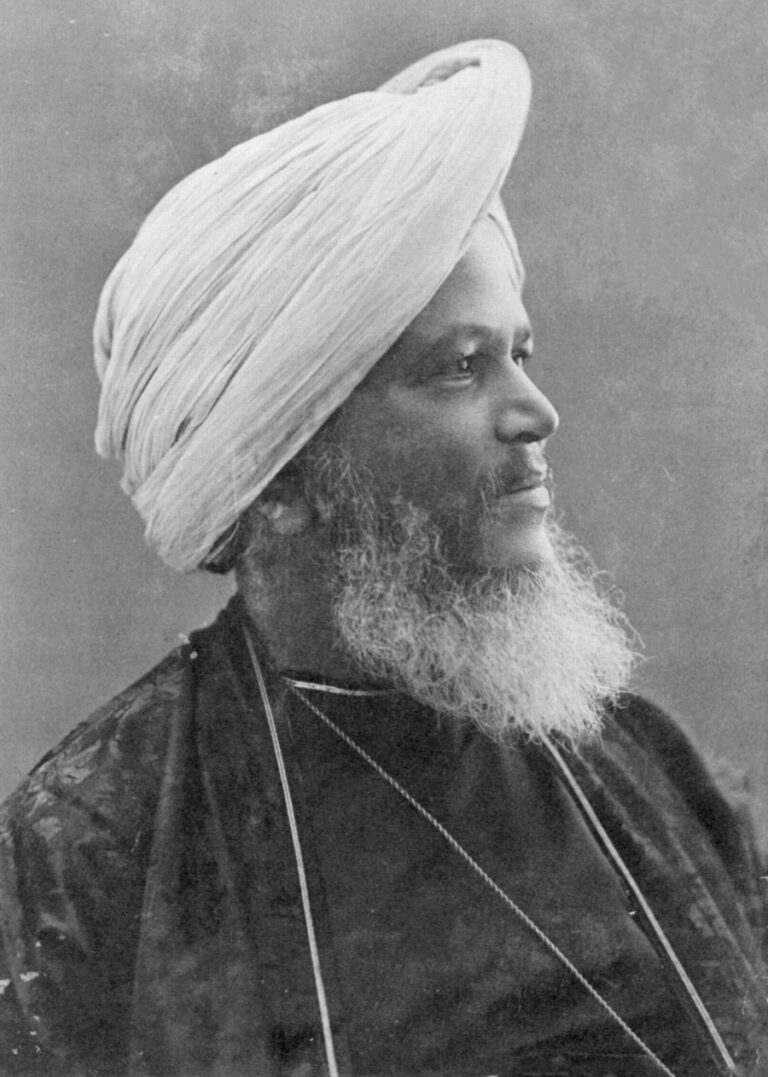

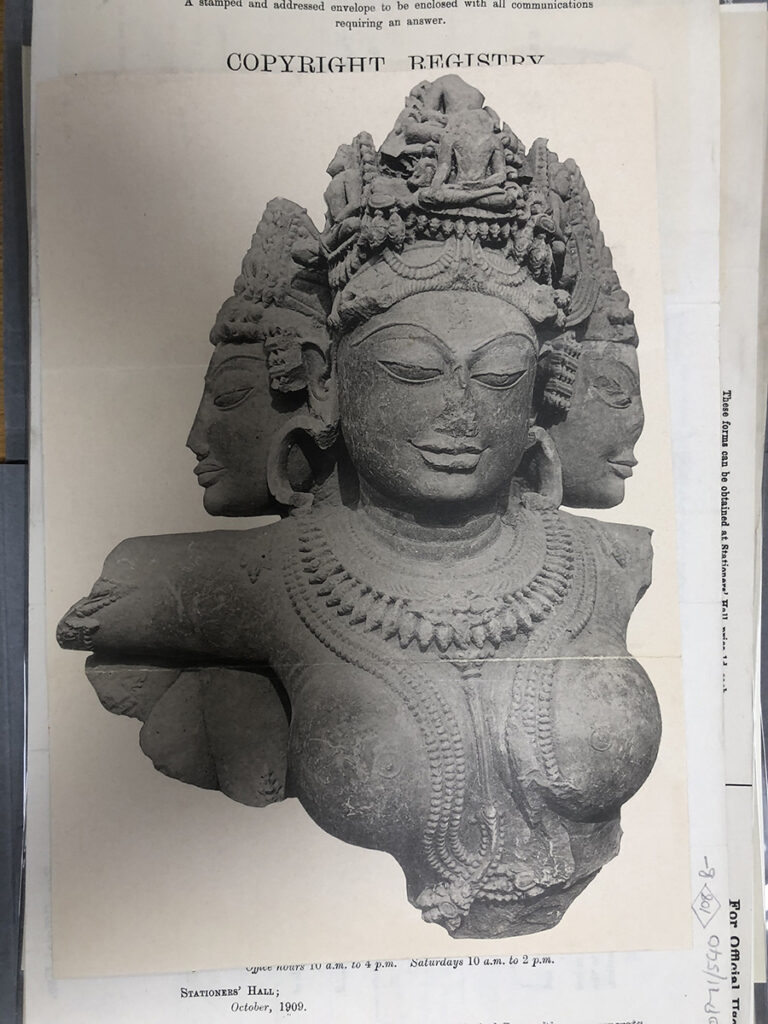

Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy

Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy was an influential art historian and philosopher who became famous for his efforts to educate people in the West about Indian art. He was born in Sri Lanka (known at the time as British Ceylon). In 1909, he registered 19 photographs for copyright protection, many of which are records of art and sculpture. During this period, he often worked with his wife Ethel Mary Partridge, who was an English photographer, so it is possible that she was involved in the production of some of these photographs.

Bourne and Shepherd

Bourne and Shepherd was a photographic studio founded by two British photographers, Samuel Bourne and Charles Shepherd, in Shimla in 1863. The company expanded over the course of the 19th century, opening several other branches across India.

Bourne and Shepherd worked as official photographers for the Delhi Durbar commemorating the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary as Emperor and Empress of India in 1911. There are 91 photographs registered by Bourne and Shepherd in the copyright collection, all registered between 1876 and 1909, and they worked with a range of other photographers as part of their business, including Frank Harrington. The studio operated continuously until its closure in 2016.

The copyright collection of photographs

The photographs presented here can all be found in record series COPY 1, which consists of photographs registered under the Fine Arts Copyright Act of 1862 with the Stationers’ Company. For more information on accessing this collection, please see our research guide to Intellectual property: photographs, artwork, literature, music and advertising registered for copyright 1842-1924 (and 1887-1955).

The photographs found in the copyright collection provide us with an intriguing window into a commercial photographic industry which was expanding in India in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By their nature, these records are limited to only those photographs which had a potential commercial value, particularly in Britain. They can therefore only give us a small and limited insight into a much larger and more complex story, but they certainly offer potential for further research.

Footnotes

- Stuart Macmillan, ‘Colonial Representations of British India: A Description and Analysis of the First Twenty-Four Issues of The Indian Amateur’s Photographic Album’, thesis, (Ryerson University and George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film, 2011), pp. 18-19

- Komal Chitnis, ‘Gateway Of India: The Birth Of Photography In 19th-Century Bombay’, Sarmaya, 27 May 2019 [accessed 04/08/2022]

- John Falconer, ‘”A pure labour of love”: A publishing history of the people of India,’ in Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place, edited by Eleanor M Hight, Gary D Sampson, (New York, 2004), p. 58

- Stuart Macmillan, p. 14

- Ibid., pp. 33-34

- Eisha Nair, ‘Who is an Indian – Crafting Identity Through Photography’, Sarmaya, 1 January 2021 [accessed 04/08/2022]

- Diva Gujral and Nathaniel Gaskell, Photography in India: A Visual History from the 1850s to the Present (2018), p. 53

- Sugata Ray, Ecomoral Aesthetics at Mathura’s Vishram Ghat, 2016 [accessed 04/08/2022], p. 68

- Entry form, Copyright Office, Stationers’ Company, 1909. Catalogue ref: COPY 1/538/167

Any ATW PENN photographs in the archive?

Excellent memories. Keep sending them. I’d like to see some pictures of the SS Ganges 1895 to Guyana (formerly British Guiana). The passenger list would be helpful. Thanks.

Fascinating. Both grandparents and parents were part of the Indian scene and followed the summer tradition of going to Simla during the summer. I have a relative who has recently been back to Simla and even found the old bungalow still occupied. She made herself known and in the best traditions was royally entertained.

My family has many photos from Indian cotton mills from the late Victorian era. I wonder if anyone at the National Archives is interested in seeing them?

Katherine -As family history questions are not permitted, this is just a comment but may not pass the moderators. As an intermediary between family members I have received an extensive history with photographs of a Howells family originally from Swansea in the 19th century, and subsequently in England, Denmark and Scotland, but not India. The author and family member now lives in Seattle.

Maybe just a co-incidence of a relatively common family name. I am not related.

A family ‘connection’ travelled to India as part of the ‘press corps’ accompanying the Duke and Duchess of Connaught from December 1902 to January1903. For many years I thought the very small script surrounding photos (on postcards typical of the period) was from the family connection but In recent years I am convinced they are an early form of ‘spin’ from the royal group. We have HMS Renown leaving London, Genoa, Alexandria(pyramids and Sphinx) and passage through the Suez Canal to Bombay, Delhi and the great Coronation Durbar in Calcutta and the return to London and Dublin. The postcards are produced by Royal Chain Postcards 14 Norfolk Street London WC. Postage stamps mirror the locations. One PC credits the photo to Elliott and Fry. From other postcards I think the sender John McGill travelled back via Cape Town, West Africa and the Canary Islands.

In the 1960s I worked in southern Nigeria and more recently (2009) visited India and mused that the Gateway to India in Mumbai had not been built when the postcards were sent.

Margaret Rae.

My grandfather was presented with an Albert Medal by King George V at the Dehli Durbar in 1911. Are there any photographs that show this presentation? (Arthur Robinson)

Fascinating – would be a good online talk. Living so far from you – it is wonderful to engage in your thought provoking talks. Thank you so much.

This article/blog is fascinating, have passed it on to a friend who was born in Darjeeling and I know will appreciate it

Very interesting…especially how the white gaze influenced subject matter and focus. Can I also commend to the viewer the SOAS collection in the senate House library. just down the road. As a graduate student researching early age anomalies in the Indian Census I found myself drifting into depression extracting data from the dusty census records . Frequent escapes into the wonderful collection of photogravure volumes in the adjacent room kept my sanity and led to a love of India and culture that remains to this day.

My grandfather was born in India and was an amateur photographer there in the 1890s-1906 while he served in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers and the Unattached List of Bengal. We have glass slides from that era as well as family and other photographs, for example, of Simla. In addition, I have my grandmother’s collection of postcards of India circa 1906-1908. They definitely round out the written histories and show life experienced by ordinary people both Indian and English.

Excellent! I would be curious to know how the National Archives obtained this collection…how it came to us.

In response to Jeanne Kelly:

I do hope so – I’m sure lots of us would like to see them!

Very interesting article, thank you, from both the photographic and genealogical perspectives.

anyone has old postcards of india? I am interested

I have a box of glass slides which belonged to my grandfather. He took them in India in the1890s. But I also suspect some were commercially bought. Any ideas how I can tell which are which?