Clothes are not just essential for warmth and modesty – they can be for so much more. They can be a source of joy or misery, a memory, a celebration, a disguise, a means of self-expression or a way of proclaiming allegiance to the tribe. They can attract judgement, compliments and condemnation. They can gild the lily or disguise the unmentionable. They can proclaim your age, your era, your politics or your rebellion. They can be serviceable, impractical, ugly or beautiful. They can also tell stories.

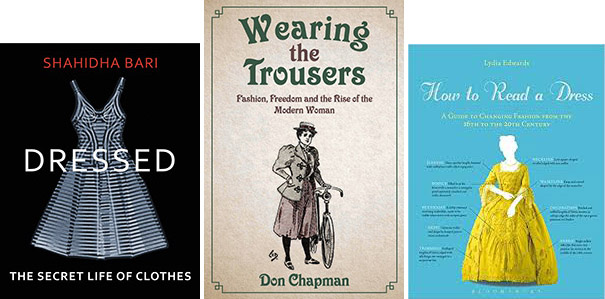

Dressed: The Secret Life of Clothes looks at what our clothes say about us and what we say about them. An eminently readable study spanning art, film and philosophy, the book examines the social history of clothes as a means of conscious or unconscious self-expression, and as fashion, armour or deception. It has some amazing pictures – Alexander McQueen’s Armadillo shoes, Leonardo da Vinci’s handbag sketches – but this is much more than merely a picture book.

From the subtext behind Cinderella’s glass slipper, to a look at Cary Grant’s suits (did you know his father was a tailor?) or the implications of Tippi Hedren’s mink coat and alligator bag in ‘The Birds’, your clothes clearly often say more than you think. Author Shahidha Bari takes clothes seriously, perhaps a little too seriously at times, as she examines how we dress in terms of freedom, privacy and objectification. You may never look at that cardigan in the same way again.

Wearing the Trousers by Don Chapman is more of a chronological study of changes in clothes as a symbol (and indeed a reward) of emerging liberation. At the turn of the last century the rational dress movement (also known as the Victorian dress reform movement), championed by campaigners such as Lady Harberton, rebelled against the constraints imposed on women by what they wore. In a time when crippling corsets could ruin your health and heavy full skirts made movement difficult, Lady H decried ‘the sinister influence which fashion exercises upon our home and social life’.

Although we tend to think of the 19th century as the heyday of oppressive fashions, it wasn’t until as recently as 1968 that Oxford University ruled that women students could wear trousers with their caps and gowns, and in 1999 the mother of a 14 year-old Tyne and Wear schoolgirl had to take her case to the Equal Opportunities Commission to win a ruling to allow her daughter to wear trousers to school.

How to Read a Dress by Lydia Edwards sashays down the historical catwalk, examining women’s costume from the 16th to the 20th century. Overviews of the trends of the period are accompanied by full-colour photographs of historical garments (mostly from museum collections) highlighting important features and commenting on shape, fabric and accessories.

It is fascinating to rifle through this pictorial dress-up box and see styles come and go, and then imagine what you might like to wear. My pick would be the amazing grey satin evening coat from 1912, its shape influenced by the craze for all things Japanese. The draping really makes the satin ripple with light.

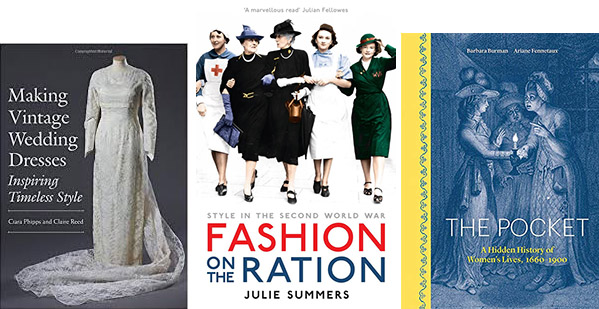

The ultimate dress is, of course, the wedding dress. It has to be perfect and you only get one shot at this (not true of course but we cling to that romantic illusion). Making Vintage Wedding Dresses is a glorious celebration of wedding dresses from the 1920s to the 1960s. On show are dresses from fabulous confections of lace to slim and elegant pillars of silk. What’s even better is that the book contains patterns to help you recreate your own vintage wedding gown.

The ultimate dress is, of course, the wedding dress. It has to be perfect and you only get one shot at this (not true of course but we cling to that romantic illusion). Making Vintage Wedding Dresses is a glorious celebration of wedding dresses from the 1920s to the 1960s. On show are dresses from fabulous confections of lace to slim and elegant pillars of silk. What’s even better is that the book contains patterns to help you recreate your own vintage wedding gown.

Julie Summers’ Fashion on the Ration is less pictorial than the previous titles mentioned but is nevertheless just as interesting. The author discusses how, despite privations, fashion in the war years became an act of defiance and a way of maintaining dignity and hope. Clothes rationing – the dreaded utility orders, ‘Make Do and Mend’ and women’s uniforms – are all discussed in some detail using diaries, fashion magazine archives and personal stories.

Lastly, Barbara Burman’s The Pocket is a particularly fine example of how a study of what women wore can reveal a wealth of social history. The author focuses on pockets in the everyday lives of women in the 18th and 19th centuries. At that time a pocket, rather than being a tiny dress-specific dumping ground for bus tickets and used hankies, was a tied-on accessory more akin to the modern handbag. While today we tend to minimise what we keep in our pockets to avoid the suggestion of hippo-hips, our great-great-grandmother’s tie-on pocket could contain anything from a penny to a sketchbook or bible to a live duck. Burman has examined these tie-on bags held in museum collections around the country, and has used them to tell the stories of women from all walks of life – from duchesses to prostitutes.