Big Draw logo

What can you do with a trusty pencil, a clean sheet of paper, a clipboard and an archive? Well, the answer is draw! Many people pick up their sketchbook on their way out to galleries and museums – but not many people think to do so in an archive.

However, the Onsite Education team here at The National Archives hoped to change that with our recent learning workshop for families.

One of our hard-working sketchers

We decided to team up with The Big Draw to encourage our local families to pick up their pencils and sketch, doodle, scribble and draw their way through our collection. For their 2016 campaign, our friends at the Big Draw have struck upon the theme of STEAM power, ‘bringing together Science, Technology, Art, Engineering and Maths. STEAM recalls our Industrial past and the fusion of creative innovation, enterprise and the arts.’

In preparation for the event, and with ‘STEAM Power’ as my mission, I set off to research documents which best represented this theme. The National Archives Flickr account is always my first port of call when embarking on research for family events, and it didn’t disappoint me. What a glorious collection of delightfully draw-able documents! Propaganda posters, medieval illuminations, 19th century photography… Yet none of these seemed to quite fit our brief.

I continued on, mining the records knowledge of my colleagues, scrolling through our Image Library and searching our catalogue until I finally struck upon an idea: maps.

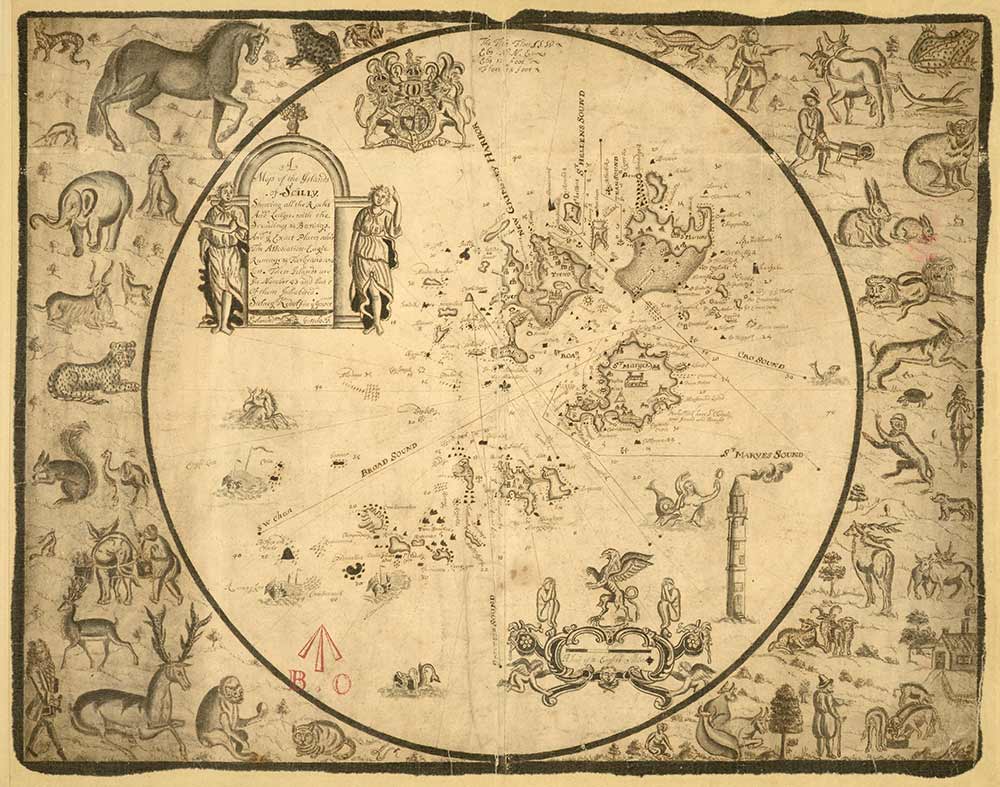

Scilly Isles (catalogue reference: MPH 1/368)

What better way to represent the successful blending of artistic and technical skill than a map? The craft of cartography surely relies on this combination to accurately and accessibly convey spatial reality. With our abundant collection of maps reaching over the six million mark, the challenge would be choosing which maps to draw.

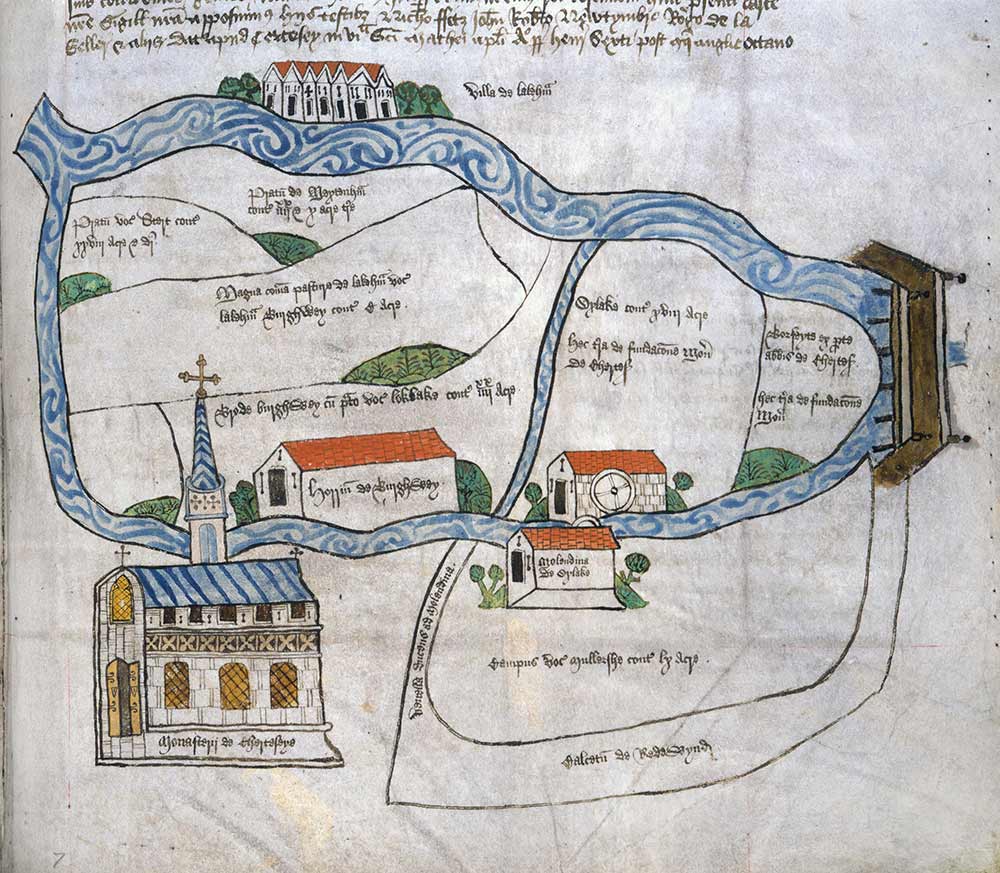

Chertsey Abbey, 15th century (catalogue reference: E 164/25 f222)

Before I could go any further, I needed to think more about why drawing in an archive is worthwhile. Not only is it a fun way to pass the time, but it also develops skills that are necessary for learners of all ages. For example, drawing requires close and careful observation, a skill which is essential to anyone, young or old, who works with historical documents. Furthermore, by reflecting on the artistic and technical qualities of the document, it forces learners to consider its authorship: who created it? Why? What message were they trying to communicate?

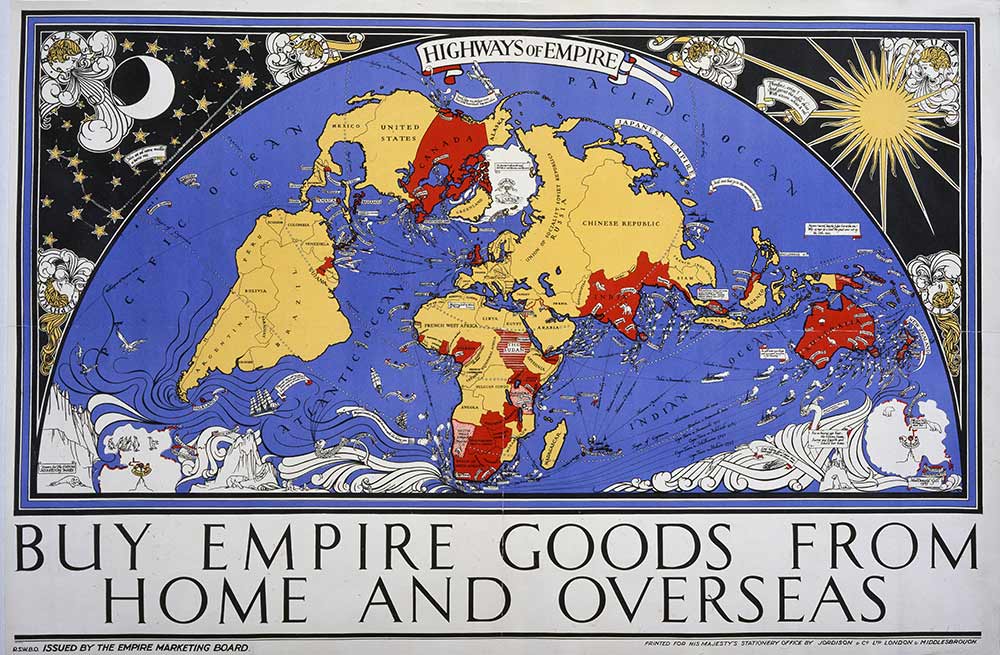

Now, maps certainly have a long history of communicating more than just geographical information. Maps have been used to encourage the buying of goods, to communicate power, or to bear witness to the impact of an historical event.

Empire Marketing Board 1927-1933 poster, Highways of Empire artist MacDonald Gill (catalogue reference: CO 956/537)

So, our family learning workshop started by exploring a small selection of the maps held here at The National Archives and considering the purpose of each of these. We then picked up our pencils, chose our favourite map, and created a sketch inspired by what we’d observed. Some learners loved the elegant bend of the river in the Chertsey map. Others delighted in the animals bordering the map of the Scilly Isles and included their own favourite animals in their drawing. Some drew maps from their imagination, or their school, or their dream desert island. As you can see, the Keeper’s Gallery was, for a short while, jam-packed with dedicated sketchers.

- I wonder what he’s sketching?

- A family working together to consider the messages communicated by the maps

Given this clear enthusiasm for drawing our collection, the Onsite Education team would love to hold more family learning workshops which include drawing activities. I wonder where in the collection our sketchbook will take us next? Suggestions are very welcome.

OH – if you only knew how, when I find such as the above maps etc. I wish I could just walk into TNA again!

Living in Texas!J

JT.