Finding documents in the archives that relate to trans or gender non-conforming people from the past can often be difficult. For many, the possibility of living outside of the male-female binary was inconceivable, while those that did successfully transition or ‘pass’ often kept the details about their lives to themselves, and most often, to their graves.

There are, however, many instances in which archival records can give some insight into the lives of LGBTQ+ people from the past. And while these documents typically expose the injustices faced by those that did not conform to societal norms, they are also important because they highlight the existence of queer and trans people throughout history.

Dr James Barry (c. 1795-1865)

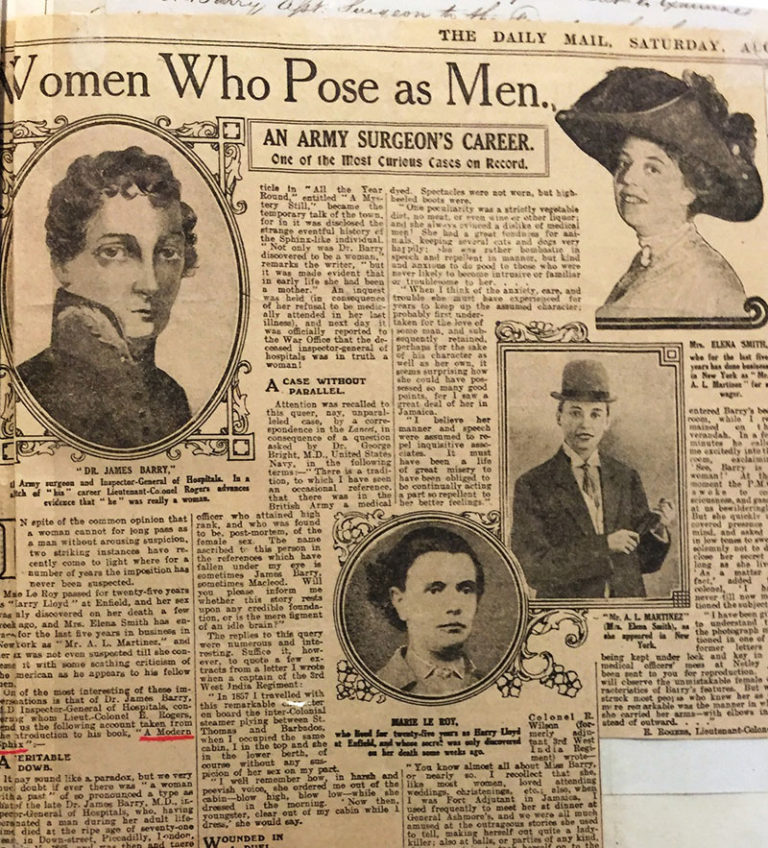

Dr James Barry, an accomplished 19th-century British military physician, is a well-known example of someone whose life did not necessarily conform to stereotypical gender norms. Born biologically female at the end of the 18th century, it was not until his death in 1865 that his biological sex was publicly (and unfairly) revealed.

It is important to recognise that contemporary understandings of gender can complicate the ways in which we view and interpret the past, for we are reliant on the terminology that we are familiar with today. However, Barry lived consistently throughout his public and private life as a man, and it is important to respect that this is how he chose to identify. This blog post will be using he/him pronouns.

‘As you furnished the certificate as to the cause of his death, I take the liberty of asking you whether you yourself ascertained that he was a woman […]?’

Letter from Registrar General George Graham to Staff Surgeon Major Dr McKinnon. Catalogue ref: WO 138/1

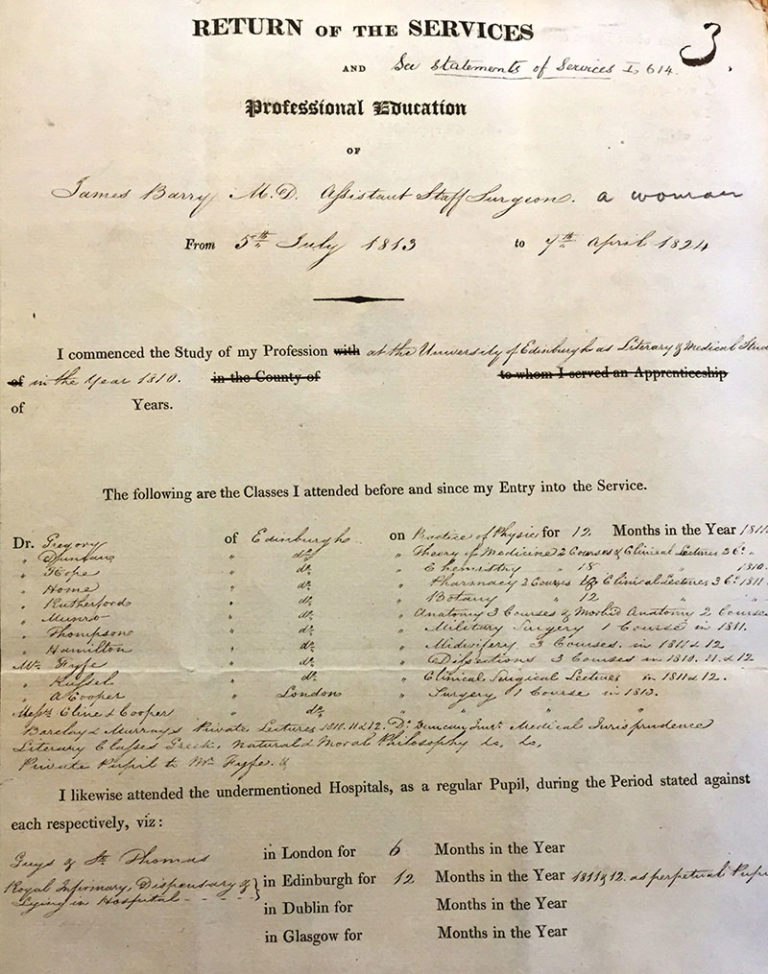

One of the earliest-known documents that can be attributed to Barry, which can be found at The National Archives, provides insight into the early years of his medical career (WO 25/3910 – Records of Service, Officers). Barry qualified as a Doctor of Medicine from the University of Edinburgh in 1812, moving to London soon after to complete his studies, and graduating from the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1813. He then commenced his service in the army as a military doctor, traveling all over the world, in particular, Cape Town, where he became the first known surgeon to have performed a successful birth via c-section.

A ‘Brute’ and a ‘Blackguard’

Barry earned himself a reputation, not only as an excellent surgeon but also for being a feisty figure. A newspaper report (WO 25/3910 – Daily Mail) published after his death reveals that many regarded him as being ‘imperious in manner and officially dictatorial’, and while working in South Africa, Barry was supposedly shot in the leg during a pistol duel with a commanding officer in the British Army. It is also believed that while serving in the Crimean War, Barry had ‘a very public altercation [with Florence Nightingale …] who later called him a “brute” and a “blackguard”’[ref]‘Dr James Barry and the specter of trans and queer history’, E E Ottoman[/ref].

While the origins of their alleged dispute are unknown, stories about Barry’s strong will and gutsy nature have an afterlife of their own.

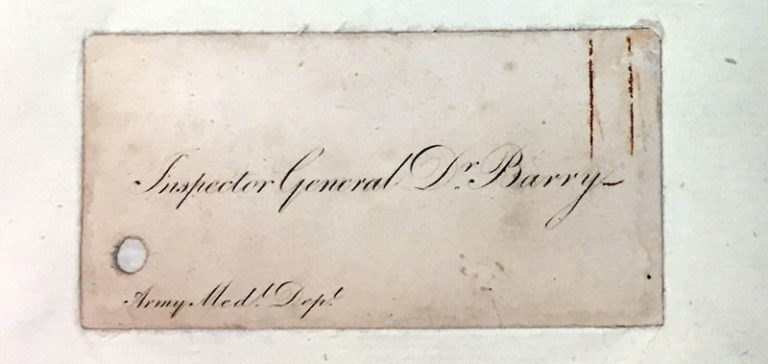

Despite this, Dr James Barry was highly regarded throughout his lifetime as being a compassionate and talented medical practitioner, who sought to ensure the availability of medical care and proper sanitation for people all over the world. As a result, he was promoted to Inspector General of Hospitals in 1851.

‘Not a secret of mine’

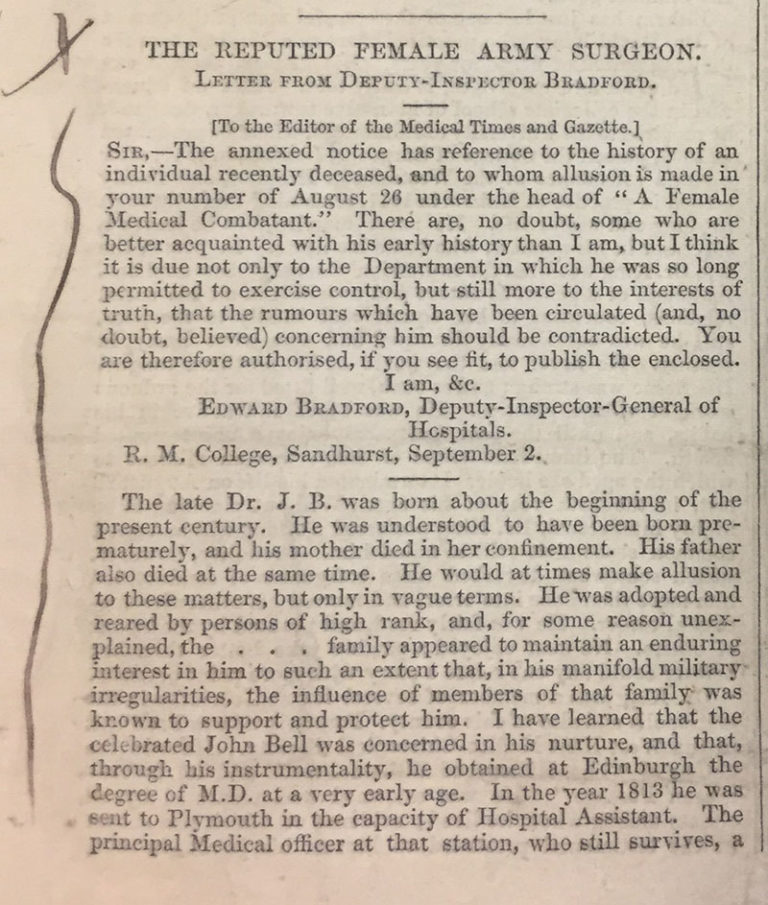

Barry retired from both medicine and the military in 1864, and died a year later in London. Despite his personal wish that his body should not be examined under any circumstances following his death, a disgruntled former servant, who claimed to have attended to Barry’s unclothed body, approached Staff Surgeon Major Dr McKinnon with knowledge concerning his biological sex. A letter from McKinnon (WO 138/1) states that ‘the woman seemed […] to think that she had become acquainted with a great secret and wished to be paid for keeping it. I informed her that all Dr Barry’s relatives were dead and that it was not a secret of mine’. She quickly took this information to the press, and articles such as ‘The Reputed Female Army Surgeon’ were published around the world (WO 138/1, Medical Times and Gazette).

In 1865, the revelation of Barry’s supposed biological sex was a clear violation of both his privacy and personal wishes. 155 years later, the significance of this knowledge, in combination with the archival materials that are available at The National Archives, is clear: it provides increased visibility of queer, trans, non-binary and inter-sex identities prior to the 21st century.

‘whether Dr Barry was male, female, or hermaphrodite I do not know, nor had I any purpose in making that discovery as I could positively swear to the identity of the body as being that of a person whom I had been acquainted with as Inspector General of Hospitals for a period of eight or nine years’

Letter from Staff Surgeon Major Dr McKinnon. Catalogue ref: WO 138/1

Further reading

For more information on Dr James Barry from fantastic LGBTQ researchers, be sure to check out the following:

- David Obermayer’s research blog, ‘Notes on a Gentleman’

- E E Ottoman’s research, ‘Dr James Barry and the specter of trans and queer history’

- Jack Doyle’s article, ‘“The Trans Take”: Towards a Transgender Public History’

- Catherine Baker’s article for History Today, ‘Monstrous Regiment’

Mollie Clarke is a PhD student at the University of Roehampton, working on ‘Female Cross-Dressing, Genre and Popular Literary Forms, from 1840 to 1870’.

This is a really neat piece, Mollie. (And I’m only happening upon it today, after a chance visit to the Thackray Museum of Medicine in Leeds, where I overheard another visitor exclaim after reading a short piece about Dr James Barry.)

More broadly, your introductory observations – about how “finding documents that relate to trans or gender non-conforming people from the past can often be difficult”, and that “there are, however, many instances in which records can give some insight into the lives of LGBTQ+ people from the past. And while these documents typically expose the injustices faced by those that did not conform to societal norms, they are also important because they highlight the existence of queer and trans people throughout history” – all really resonated with / mirrored my own research a couple of years ago into medieval LGBTQ+. In case of interest, please see the 700-word blog at: https://thehistoriansmagazine.com/shedding-light-on-medieval-lgbtq/