The Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) was founded in November 1917. The intention was for them to undertake shore-based duties, in order to free up sailors to go to sea. ‘Free a man for sea service’ was a slogan commonly found on recruitment posters. The terms and conditions booklet for the WRNS starts off with the following sentiment:

‘The Women’s Royal Naval Service has been formed because there are certain duties, hitherto performed by men of various naval ranks and ratings, which can be done equally well by women, whose substitution will release men for more strenuous branches of naval service.’ (ADM 116/3739)

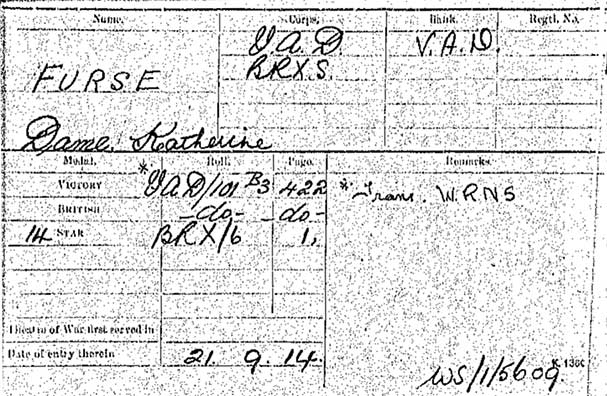

The first director of the WRNS was Dame Katherine Furse. Furse was initially a member of the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) and on the outbreak of the war she was chosen to head the first VAD unit sent to France. Aware of her administrative abilities, the authorities later placed her in charge of the VAD department in London. However, Furse was unhappy about her lack of power to introduce reforms. In November 1917, she and several of her senior colleagues resigned, due to a dispute over the living conditions of the VAD volunteers and the Red Cross refusal to co-ordinate with the Women’s Army group. Almost immediately after this, she was offered the post of director of the WRNS.

Medal card of Katherine Furse (catalogue reference: WO 372/23/15091)

Both officers and ratings were classed as either ‘mobile’ or ‘immobile’. Mobile meant that you were willing to move/travel to wherever required in the UK; immobile meant that you preferred to stay at, or near to, home. Immobile ratings were most often found in London, or at naval bases such as Portsmouth.

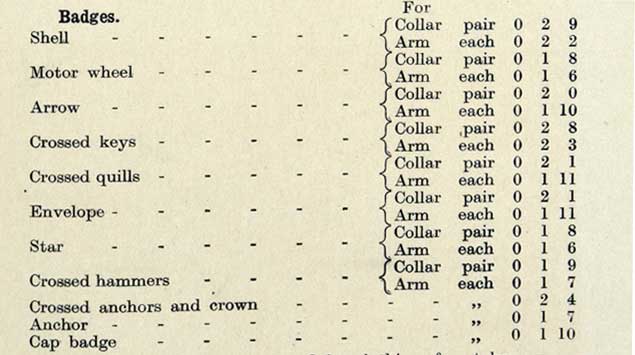

Initially, WRNS undertook domestic duties such as cooking and cleaning. But this later expanded to a greater variety of roles, such as that of wireless telegraphist or electrician. Most were given a trade category, and these were denoted by blue, non-substantive trade badges which were worn on the right arm. The main trade categories were as follows:

scallop shell = household worker

three-spoked wheel = motor driver

arrow crossed by lightning flash = signals

crossed keys = storekeeper; porter; messenger

envelope = postwoman; telegraphist

crossed hammers = technical worker

star = miscellaneous

The various badges and costs associated (catalogue reference: ADM 116/3739)

In terms of the actual enrolment into the WRNS, the forms seem particularly lengthy. Of course, one had to answer the usual questions of name, date of birth, age, address. Nothing out of the ordinary for today. There are also many statements that one had to agree to, such as:

‘Do you agree that in the event of your being guilty of any act or neglect in breach of this contract or of any of the rules, regulations or instructions laid down from time to time for this Service, you will be liable to a fine?’

There are quite a few statements relating to the potential of being fined.

The initial application form also has a host of questions relating to areas such as the nationality of your mother and father at birth, nationality of your husband, and so on. But I think my favourite part of the form is that, in the section dedicated to references, one of the conditions is that one of the referees has to be a woman.

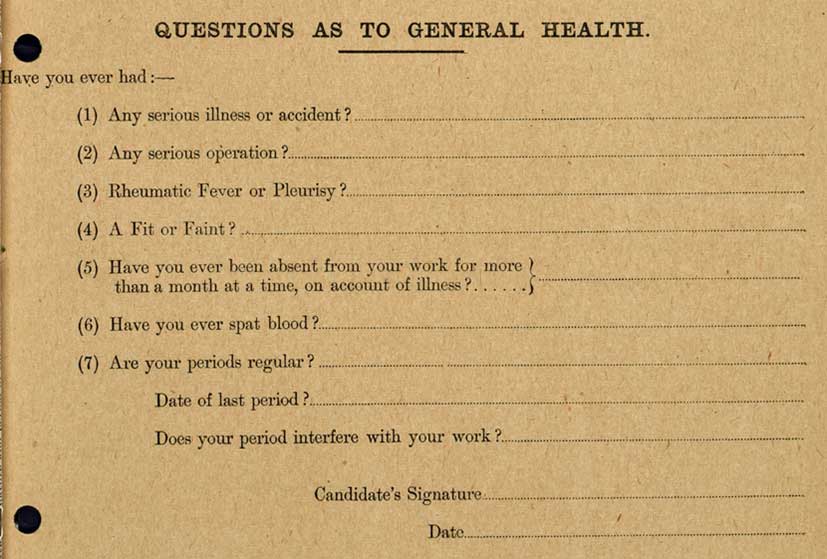

Understandably, women had to undertake a medical examination upon entry, which is fair enough. But this is also an area where I become almost incredulous at what could be asked. Under questions as to general health, it starts off with questions that we might expect to see on medical forms nowadays – queries relating to any recent serious illness or accident, or if whether any serious surgery had been carried out. And then you come to question number 4 which asks if you’ve ever had a fit or a faint. I can assure you, that that would certainly have not been asked of a man. And then number 7 is the real doozy – this section asks:

Are your periods regular?

Date of last period?

Does your period interfere with your work?

Just imagine if that was asked nowadays…

Questions as to general health section of the WRNS application (catalogue reference: ADM 116/3739)

At The National Archives we have the service records of over 5,000 women who served in the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) between 1917 and 1919. The original records are grouped in series ADM 318 for officers and ADM 336 for ratings or other ranks. You can search the records by first name, last name, and official number. Officers who resigned in 1918 for personal reasons are not included in these records. Look at the series ADM 321 instead, which contains two registers of appointments: promotions and resignations of WRNS officers from 1917 to 1919.

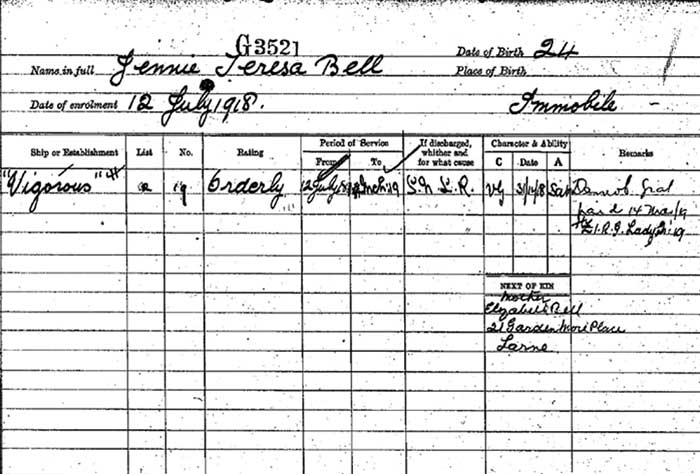

I’m just going to pull out a few interesting examples of service records relating to the WRNS that I’ve looked at so far. The following were all ratings in the WRNS. This, for Jennie Teresa Bell, is a common example of what you will normally find on a service record.

Service record for Jennie Teresa Bell (catalogue reference: ADM 336/26/520)

The part that I particularly want to highlight is the letters under ‘If discharged, whither and for what cause’: SNLR, which stands for ‘service no longer required’. This is a common thing to see on these papers.

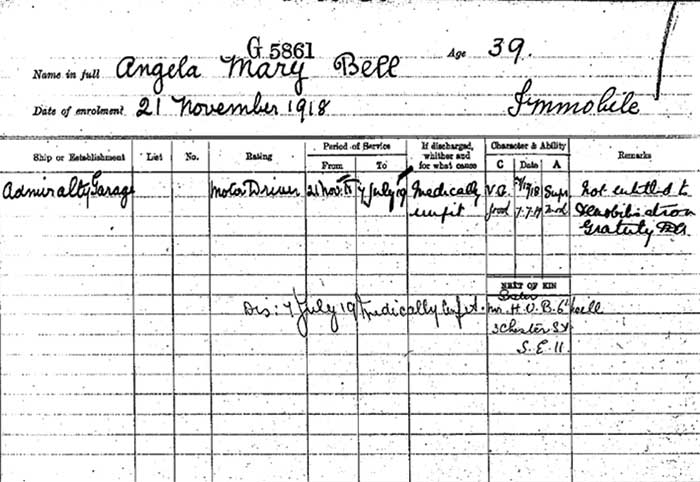

Service record for Angela Mary Bell (catalogue reference: ADM 336/28/854)

The next one, for Angela Mary Bell, has ‘medically unfit’ under the reason for discharge, which isn’t too common in its own right. But it is definitely much more common than the note on this final record:

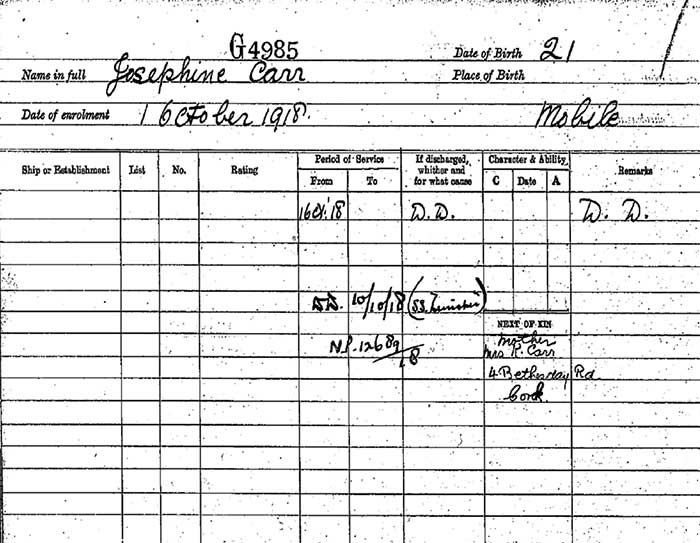

Service record for Josephine Carr (catalogue reference: ADM 336/27/980)

Here, we can see DD: this stands for ‘discharged dead’. If you know anything about the WRNS, then the name on this record might be known to you. It’s that of Josephine Carr, the first WRNS member to die on active service after the ship she was travelling on, the SS Leinster, was torpedoed.

WRNS marching in the Victory Parade, 1919 (catalogue reference: WORK 21/74)

When the First World War came to an end, the WRNS were disbanded. By the end of this period, they could count some 5,500 members. They were reformed for the outbreak of the Second World War. This time they had an even more varied list of activities which they could undertake. These new roles included responsibilities such as radio operators, meteorologists and bomb range markers. At their peak, in 1944, the numbers of WRNS officers and ratings were 74,000. After the Second World War, a small number of permanent WRNS positions were retained (3,000 of them). These were mainly administrative and support roles at Royal Navy establishments, both in the UK and overseas.

The service was finally integrated into the Royal Navy in 1993, when women of any rank were able to serve on board naval vessels as full members of the crew.

As far as the personal questions go these were the questions (and dates) asked of single mothers who were claiming social security benefits in the 1970s until due to public and Parliamentary pressure the forms and questions were changed. I notice you didn’t mention teeth which could stop men being employed in the armed services.

Are there any casualty figures for WRENs in the Great War?

I am trying to put together totals for both men and women. The men part is relatively straight forward. I can not find any for women.

Was there catagories for discharged on marriage or due to pregnancy?