Diversity Week is taking place at The National Archives

I’m particularly looking forward to the range of external talks we have organised this year, covering a breadth of subjects and archival collections. Tomorrow, Stephen Bourne will be discussing his work in unearthing Black British history. On Wednesday Dr Lesley Hall will be looking at the history of sexuality, with particular reference to the collections held at the Wellcome Library. On Thursday, our very own Chris Barnes and David Langrish will be talking about the launch of the MH 47 series online. Finally, on Friday Simon Jarrett will be exploring the history of learning disabilities and how they have been documented over time. All these talks are free and open to everyone, aimed at highlighting work happening in the field and inspiring future research. Please come along!

This year we also begin five years of commemoration of the First World War. In the past few weeks we’ve released digital copies of the War diaries online, and with Chris and David’s talk on Thursday, we highlight again the launch of the digital MH 47 series last week. What these series do, in particular MH 47, is allow us to hear the stories of the ‘ordinary soldier’, their experiences, the lives they left behind, and in some cases their desperation to not go at all.

With Diversity Week in mind, and with the upcoming LGBT history month in February, I’ve been looking at some of the ‘ordinary soldiers’ stories that became not-so-ordinary thanks to their later fame.

Much has been written and romanticised about soldiers leaving their sweethearts at home to join up, and the impact it had on them and those left at home. However, less has been focused on the relationships between those on the front line.

Wilfred Owen. Source: Wikipedia

Two of the most famous First World War poets met while convalescing in an Edinburgh hospital in 1917. Their close friendship and shared sexual orientation has raised the profile of gay soldiers fighting in the First World War and their experiences, both as soldiers and as men.

Wilfred Owen was 22 years old and an aspiring poet when he signed up and was commissioned in the Manchester Regiment. We hold his service record here at TNA (WO 138/74) and it tells of the trauma he suffered on the frontline. In April 1917, Owen was blown in to the air by an explosion while sleeping. He was subsequently trapped with the remains of a fellow Officer, the experience of which haunted him long afterwards. [ref] 1. Helen McPhail and Philip Guest, Wilfred Owen, (Yorkshire: Leo Cooper, 1998), p.65. [/ref]

Owen was eventually sent home to recover from ‘shell shock’, and was put in the care of Craiglockhart hospital in Edinburgh, where he met his friend and mentor, Siegfried Sassoon.

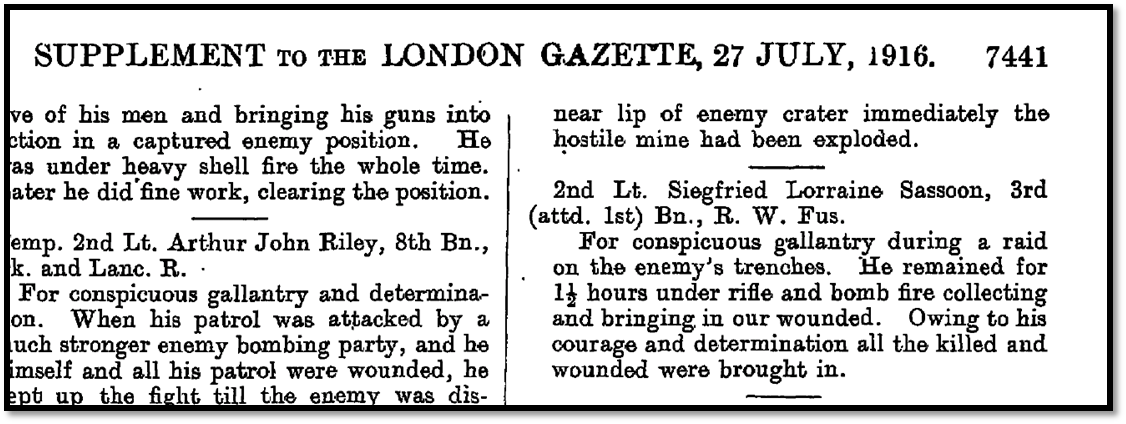

Extract from the London Gazette showing Sassoon's recommendation for the Military Cross: www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/29684/supplement/7441

In contrast to Owen, who was yet to receive any acknowledgement of his work, Siegfried Sassoon was a published poet when he joined up. He was awarded the Military Cross in 1916 but was becoming more and more disillusioned with the war and what he saw as the ‘greed’ of authorities interested only in expanding the Empire. [ref] 2. Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Siegfried Sassoon: The Making of a War Poet, (New York: Routledge, 1999), p.260. [/ref] In July 1917, a letter from Sassoon expressing his anti-war sentiments that can be found in his service record was published in The Times and read in the House of Commons:

‘I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority because I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it … I believe that the war upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation has now become a war of aggression and conquest … I believe it may help to destroy the callous complacency with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share and which they have not enough imagination to realise.’ Sec. Lt. Siegfried Sassoon, 3rd Batt: Royal Welsh Fusiliers, July, 1917. (WO 339/51440)

Siegfried Sassoon's document accusing authorities of prolonging the war, 1918 (catalogue reference: WO 339/51440)

This was a difficult event for military authorities – a respected, decorated, published Officer speaking out publicly against the war – a political nightmare. Sassoon was in danger of being court-martialed, but thanks to an appeal by his friend and fellow poet, Robert Graves, it was accepted that Sassoon’s outburst could be blamed on ‘war neurosis’ and required treatment rather than punishment. [ref] 3. Wilson, (1999), pp. 383-384. [/ref] Thus, he found himself at Craiglockhart and in the company of Owen.

Owen and Sassoon

Both Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon are widely considered to have had relationships with men, although there is no evidence to suggest they were romantically involved with each other.

Sassoon is more commonly known to have been gay, openly amongst his closest circle, having had affairs with well-known figures such as Ivor Novello, Stephen Tennant and Prince Philipp of Hesse, but constrained by the attitudes of his time as he expresses in his wish to write a book in 1921: ‘It is to be one of the stepping-stones across the raging (or lethargic) river of intolerance which divides creatures of my temperament from a free and un-secretive existence among their fellow men.”'[ref] 4. Wilson, (1999), p.1. [/ref]

Siegfried Sassoon. Source: Wikipedia

His diary records his feelings for men such as fellow poet Robert Graves: ‘There was some vague sexual element lurking in the background of our war-harnessed relationship. There was always some restless passionate nerve-wracked quality in my friendship with R.G.’ [ref] 4. Wilson, (1999), p.215. [/ref]

Both Owen and Sassoon produced some of their most famous works while at Craiglockhart together. Sassoon’s work in particular reflected on the close ties forged in the trenches that many could never leave behind, such as the guilt displayed in his poem ‘Sick leave’:

Sick Leave

When I’m asleep, dreaming and lulled and warm, –

They come, the homeless ones, the noiseless dead.

While the dim charging breakers of the storm

Bellow and drone and rumble overhead,

Out of the gloom they gather about my bed.

They whisper to my heart; their thoughts are mine.

“Why are you here with all your watches ended?

From Ypres to Frise we sought you in the line.”

In bitter safety I awake, unfriended;

And while the dawn begins with slashing rain

I think of the Battalion in the mud.

“When are you going out to them again?

Are they not still your brothers through our blood?”– Siegfried Sassoon, 1917

In contrast, Owen’s family are reported to have removed any evidence of his sexual orientation from his work and papers after his death. [ref] 5. Poetry Foundation, Biography, Wilfred Owen 1893-1918, www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/wilfred-owen [/ref]

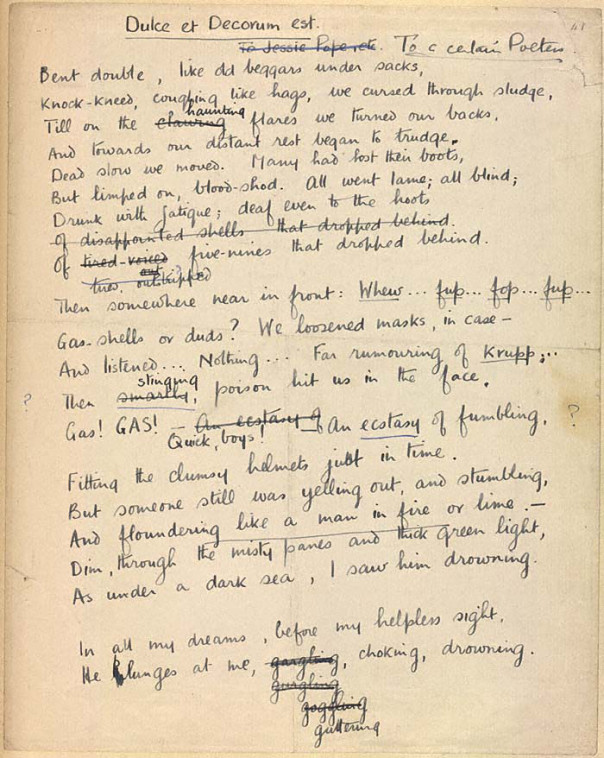

Owen greatly admired and was inspired by Sassoon’s style of writing. The original copy of Owen’s famous poem ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ (sweet and fitting it is) show’s Sassoon’s suggestions and alterations, illustrating his direct impact on Owen’s work. Click on the image below to see a large version.

'Dulce et Decorum Est' showing Sassoon's edits. Source: http://theredanimalproject.wordpress.com/2011/03/09/poets-of-the-great-war-siegfried-sassoon-and-wilfred-owen/

Sassoon has been credited with mentoring and influencing Owen’s work to the point that Owen is now considered a better poet than Sassoon, and one of the strongest ‘voices’ of the First World War, although this may be influenced by his early death and Sassoon’s later less successful poetry. It is Owen’s inscription that marks the memorial of all the War poets in Westminster Abbey: ‘My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.'[ref] 6. Westminster Abbey, Famous People & the Abbey: Poets of the First World War, http://www.westminster-abbey.org/our-history/people/poets-of-the-first-world-war [/ref]

Wilfred Owen was killed in action on 4th November 1918 while Sassoon was in England, permanently invalided out of service. Notice of his death reached his family on Armistice Day. Sassoon later took on the role of editing Owen’s poems to be published, ensuring Owen’s success as one of England’s greatest and most harrowing War poets long after his death.

For more information on LGBT history research and in particular an excellent annual magazine exploring different areas, see the LGBT History Project blog: http://lgbthistoryproject.blogspot.co.uk/.

Jenni

Very interesting. Sorry I missed it