The plan of attack was to hit the long distance footpath, the GR 223, before lunch. If we could get out of Caen, the map promised us a glorious walk through the Normandy countryside. Even archivists sometimes have the need to shake the dust from their cardigans and get away from history. So much so, that I felt the ancient abbey marked in a field (doubtless a ruin) was not going to be worth a detour.

Although it was indeed in the middle of a field, the Abbaye d’Ardenne was clearly not a ruin:

L’Abbaye d’Ardenne across the fields. Linda Stewart.

Maybe it was worth a detour after all. However, this being France, it was shut for lunch – for two hours. We wandered round the back, and came across a small rather gloomy garden, a place where something dreadful had happened, all the more shocking in such an unexpected setting.

Part of a memorial to Canadian prisoners of war executed in the garden of the Abbaye d’Ardenne. Linda Stewart.

I wanted to know more, to answer the historical geographer’s question: what happened here? It is seventy years ago today since D-Day. Records are replacing recollections. New ways of accessing those records have become available, and new disciplines have grown up to interpret them. What took place in the memorial garden is nowadays widely chronicled, in books and online. But I wanted to see what original records we had, if any, in The National Archives, and maybe retrace how the truth, of one event in all the many actions of the Normandy landings, was uncovered.

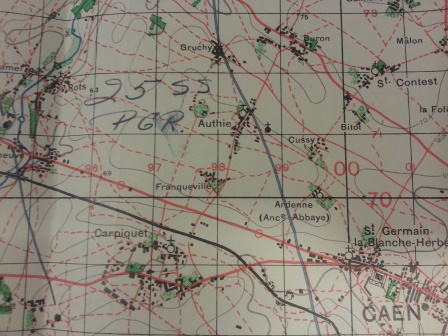

Canadian troops from the North Nova Scotia regiment, among others, landed on Juno beach on D-Day morning, with the objective of capturing Carpiquet airport, just south of the Abbey, by nightfall. They got as far as the village of Buron, to the north of the Abbey:

War Office map, 1:50,000 France, sheet 7 /F1 inserted into TS 26/850 and annotated ‘Enemy situation (from memory) from about 9 -15 June 1944’

As the North Nova Scotias were fighting their way towards Carpiquet, the cutting-edge information technologies of the war were creating records from a distance. A US reconnaissance aircraft flew over the airfield, which had been damaged by allied bombing:

Image of D-Day sortie over Carpiquet airport – reproduced by kind permission of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS)

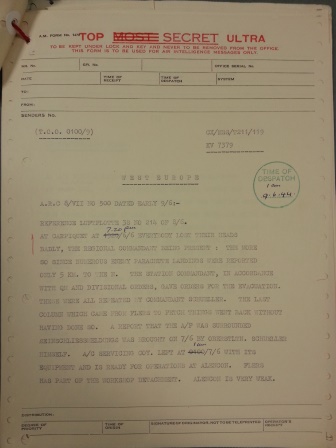

But all, at least to my untrained eye, seems quiet. However, on the ground, the programmable computer developed for the Ultra codebreaking system intercepted a message from German command: ‘everyone lost their heads badly’.

HW1/2927 Government Code and Cypher School: Signals Intelligence Passed to the Prime Minister

German troops were faced with the realisation of the scale of the invasion that was rapidly advancing across the fields; it was big, and it was coming towards them. A group of Hitler Youth, and the officer who was soon to take over as their commander, the 34 year old veteran of the eastern front, Kurt Meyer, requisitioned the Abbey. They ordered out the French families who lived there. On arrival, the usual record management practices were carried out when it’s feared the game might soon be up: a bonfire of the unit’s documents. (A few miles away in Caen, allied bombings on D-Day inadvertently destroyed a large part of the material in regional archives).

According to an inquiry launched in August 1944, TS 26/850, early the next day, the Canadians entered the village of Authie, securing it by lunchtime. But even as the joyous exchanges of Normandy cider and Canadian chocolate were taking place, the Germans launched a counter-attack from the Abbey, and retook the village. A large number of Canadians were captured, but many were shot, or deliberately run over. The rest were taken to ‘a cathedral or a monastery’ as one of the soldiers who of course couldn’t know it was the Abbaye d’Ardenne described it, for interrogation. They were then marched away to Caen.

The German troops ‘behaved in an exceedingly disorderly manner … clearly out of control’. But there is nothing in the inquiry about anything happening in the garden. The North Nova Scotia’s war diary, WO 179/2948, details the fighting and records at the end of the day a tally of 195 other ranks missing. The war diarist didn’t know or didn’t record what had happened to those who had been taken prisoner.

The original piece of evidence for the events in the abbey garden would have to wait some months, for it was neither a written record, nor an eyewitness account. The snowdrops in the garden that had been planted in a pattern came up in the wrong places. Realising the ground had been disturbed, the puzzled French families who moved back into what remained of the abbey buildings uncovered some of the hastily buried bodies.

The commanding officer, S.S. Brigadeführer Kurt Meyer, was captured in Belgium. He was tried by a Canadian Military Court on a charge of responsibility for the murder of Canadian prisoners.

He was convicted on three out of the five charges and sentenced to death, commuted to life imprisonment, on the grounds that the evidence showed that Meyer, as an individual, was not responsible for the killing of the Canadian prisoners of war by his troops. He was considered responsible as a divisional commander, though not to a degree warranting the death sentence.

Meyer was transferred to a German prison in the British sector, so we have Foreign Office files, FO 1060/514, detailing his subsequent welfare, his treatment for arthritis, the compassionate home visit he was allowed to sort out his children’s education, and, as told to an army psychiatrist, his desire to fight as a soldier in a United Army of Europe.

Reading these files, I was struck by what pains were taken to establish the truth, and above all, in a post war world, to be fair, to both sides.

After lunch, it was light relief to leave the dark deeds of the memorial garden and wander round the sunlit abbey orchard and the carefully restored buildings. In August 1944, while the inquiry into the treatment of the Canadian prisoners was going on, the battered abbey was visited by the Monuments Men, who were tasked with establishing the extent of the damage to buildings and archives. [ref] 1 Lord Methuen published his diary of his time as a Monuments’ Man. There is a copy in The National Archives Library, Normandy diary: being a record of survivals and losses of historical monuments in north-western France, together with those in the Island of Walcheren and in that part of Belgium traversed by 21st army group in 1944-45 / Publisher: London : Robert Hale Limited, [1952] [/ref]

The description of the damage that was sent to Paris is somewhat contradicted by the surviving photographic evidence which shows the almost total destruction of the buildings. This was an occasion where the rigorous reporting of the truth was not the best course of action – otherwise the powers that be in Paris would most probably have decided that the abbey was beyond saving, and ordered its demolition.

Slowly the abbey was rebuilt. In 1994, prompted by the 50th anniversary of D-Day; some of the buildings became a study centre. And as for the abbey church itself, it wasn’t open, but we peered in through a gap in the great wooden doors, and saw, not pews, but the oddly familiar sight of rows of desks, and walls of shelves. It is the library of l’Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine (IMEC), the French modern archives of the printed word. We archivists can never get away from the day job.

The story of the the Abbaye d’Ardenne and the Normandy landings is ultimately one of redemption, regeneration and remembrance. The soldiers who were executed will be remembered in a ceremony there tomorrow:

North Nova Scotia Highlanders

Private Ivan Crowe

Private Charles Doucette

Corporal Joseph MacIntyre

Private Reginald Keeping

Private James Moss

Private Walter Doherty

Private Hollis McKeil

Private Hugh MacDonald

Private George McNaughton

Private George Millar

Private Thomas Mont

Private Raymond Moore

27th Canadian Armoured Regiment

Trooper James Bolt

Trooper George Gill

Trooper Thomas Henry

Trooper Roger Lockhead

Trooper Harold Philip

Lieutenant Thomas Windsor

Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders

Lieutenant Fred Williams

Lance-corporal George Pollard (body never found)

Their names are inscribed in stone on the garden memorial, and are recorded on many websites; they will not be forgotten.

You can read more about the context to the D-Day landings on the History of Government blog.