The National Archives’ library has a fine collection of local history books. There is a particular emphasis on England, although the rest of the UK is covered, with volumes for each county as well as complete sets of local history society volumes.

Another noteworthy aspect of the library’s local history collection is those volumes in the rare book run that we have. Rare books for this library are anything published before 1800 and there are about 100 in total.

I’m going to look at a handful of these books and their authors to illustrate what we have and to give you a flavour of local history before the 19th century.

Survey of London

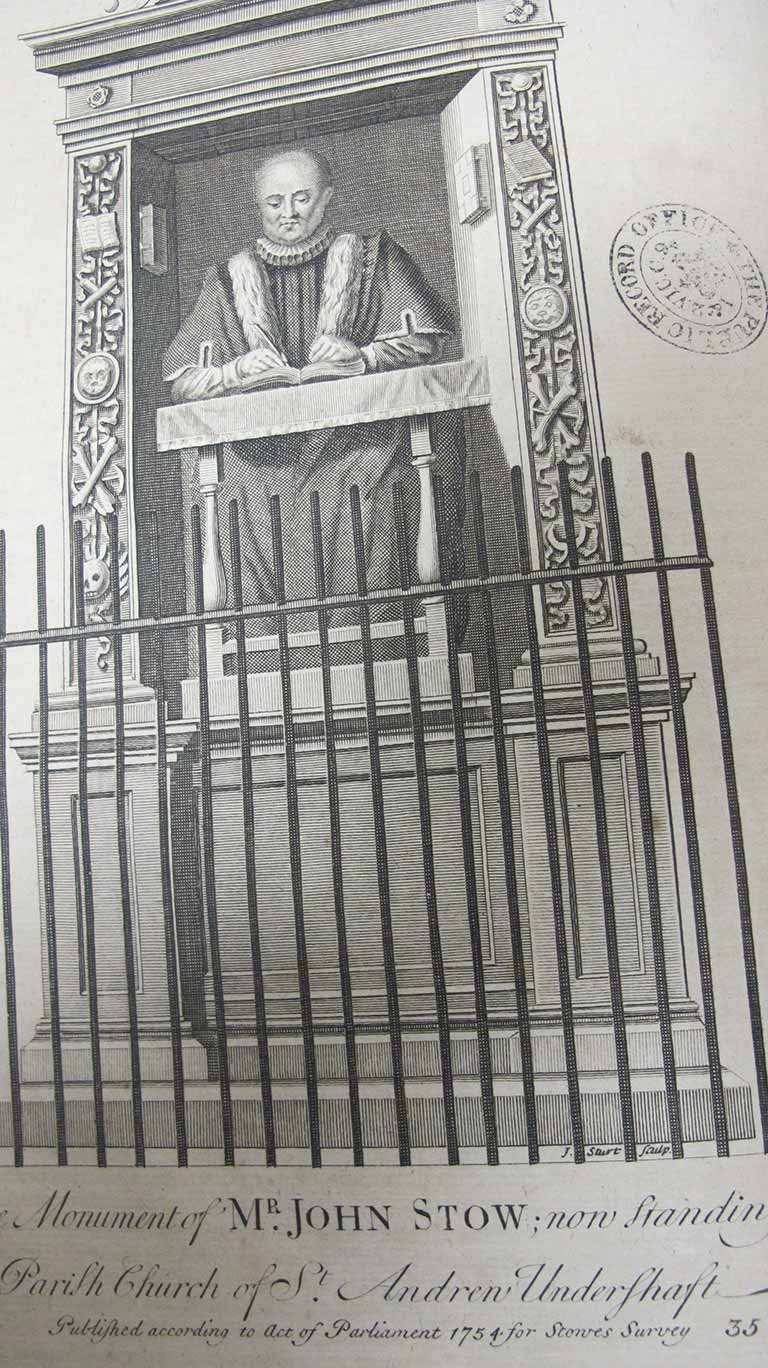

Image of John Stow

John Stow, 1524-1605, was one of the most prolific authors of his time and his book, Survey of London, 1598 is a well known work from this period. Stow was a London man who devoted much of his life to writing, learning and bookish matters.

His Survey of London remains an informative and interesting read. It is highly detailed and covers virtually of London as it was at the time. In spite of all his efforts, the literary elite of the day tended to look down on him and had little respect for his plain, perhaps unsophisticated way of writing.

That said, his work stands to this day as a reliable and workmanlike study of London thanks to his hardworking character and obsession with detail. You get the feeling Stow wasn’t interested in showing off or currying favour with the elite. His simply wanted to produce a reliable study of London. His book is an excellent way to find out more about Tudor London from a contemporary source.

The Church in Yorkshire

John Burton, 1710-1771, produced one of his key works, Monasticon Eboracesne in 1768, a survey of the lands of the Church in Yorkshire at the time. A physician and antiquary Burton was more of an establishment figure than Stow, and an altogether different kind of creature.

You get the sense of a man trying to ensure his place in the hierarchy of the establishment. However, in the process, you also get a good picture of church lands, property and politics in Yorkshire at the time. The content of Monasticon Eboracesne is very detailed and perhaps could be described at dry. The book’s style is different from that of Stow too, full of lists, facts and statistics.

However, as with Stow’s books, the research is meticulous and it does shed a lot of light on its subject. Not as wide ranging as similar studies, this book is still a useful gauge of what was considered important at the time.

History of Bristol

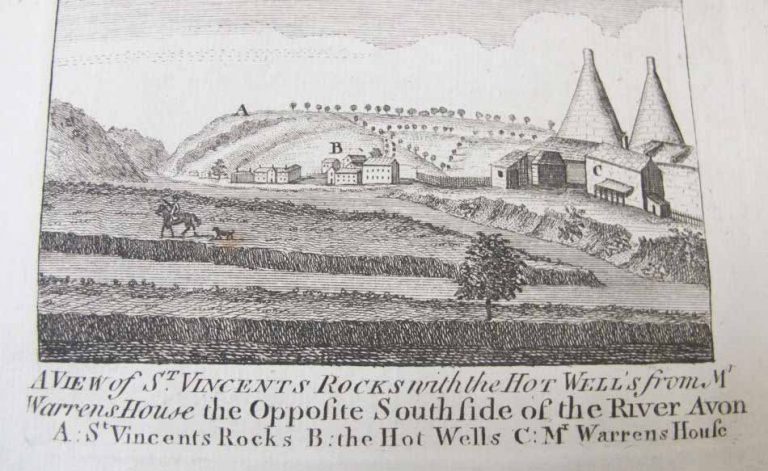

William Barrett lived between approximately 1727 and 1789 and was a surgeon and antiquary who came to know Bristol and the surrounding area well during his working life. His 1789 work, a History of Bristol is an interesting title with many plates and illustrations. Again a detailed account, it is full and varied and contains anecdotes to illustrate its story. It is in many ways an entertaining read.

St Vincent’s Rock, Bristol, in History of Bristol

Barrett’s undoing seems to have been his use of sources for his book which turned out to be unreliable, casting a shadow over the whole enterprise and even worse, Barrett’s personal reputation. Most likely a decent person , perhaps simply naïve and to an extent careless, Barrett died a broken man, unable to come to terms with what he felt was his wasted life. Had he been more discriminating in his approach, his work might have proven to be a key text. That said, it can still be considered an important work today as long as its contents are treated with a degree of caution.

Antiquaries of Cumberland

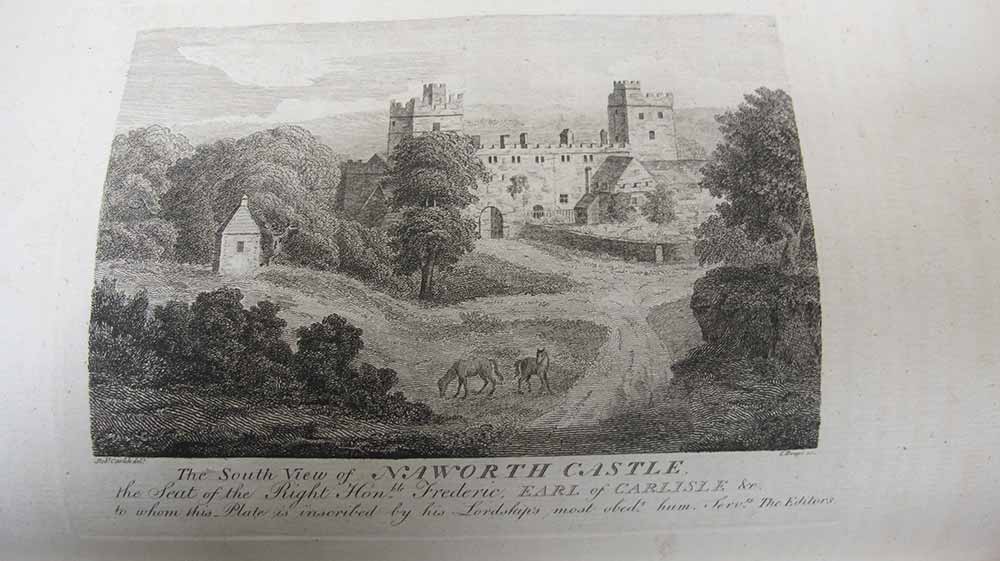

William Hutchinson (1732-1814) had his History of the Antiquaries of Cumberland published in 1794. This work is another good example of a local history title from this period. Full of detail and maps and illustrations, it covers a wide range of subjects: history, topography, local people and natural history are all covered. Again the style and varied content make for interesting reading, and it gives you a good all-round picture of the area.

Naworth Castle Cumberland, in History of the Antiquaries of Cumberland

All these books provide a good sense of the places and the times that they describe. The men who wrote them give you another indication of what was going on at the time. They were often described as antiquarians, and most were well-off and with lots of spare time; they would have had to be, given the amount of work sunk into these books.

The tone of these books – a mixture of factual detail and chatty, semi-informal style – makes them easier to read, not unlike travel books today. All in all, while not without their flaws and sometime difficult gestation, these titles and many others like them are a helpful source for anyone who is interested in the England of this period.

The rare books are available for consultation for any visitor to the National Archives with a reader’s ticket.