The National Archives puts a lot of emphasis on digitisation – both of our own collections as well as external ones – as a vital tool to preserve materials for future generations and widen access to historical documents.

In this context I was given the opportunity to prepare and conserve the Adamah Family Collection prior to it being digitised by our in-house team of digitisation experts. This was a challenging project, which required a larger scope of treatments than is usually necessary in pre-digitisation.

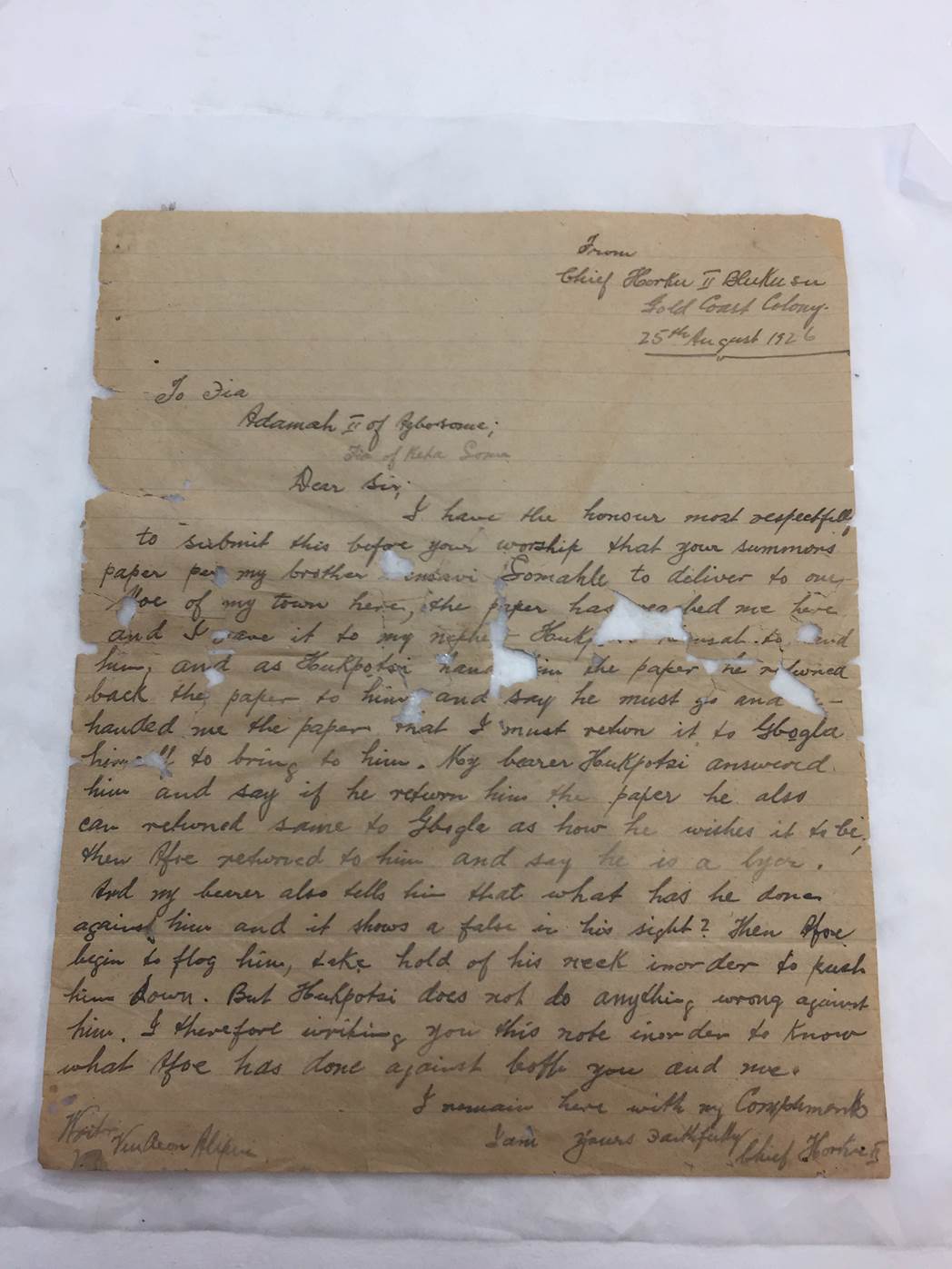

This collection came as an external digitization project from the Black Cultural Archives (BCA), located in Brixton, London. It had been donated to the BCA by a family of chiefs in Ghana, the Adamah family, and reflects their daily life and their own migratory history. It contains a varied collection of documents dating from 1885 to the 1950s, including letters, newspaper articles, photographs and a poster from the Second World War.

The Adamah family (image provided by The National Archives’ scanning operators)

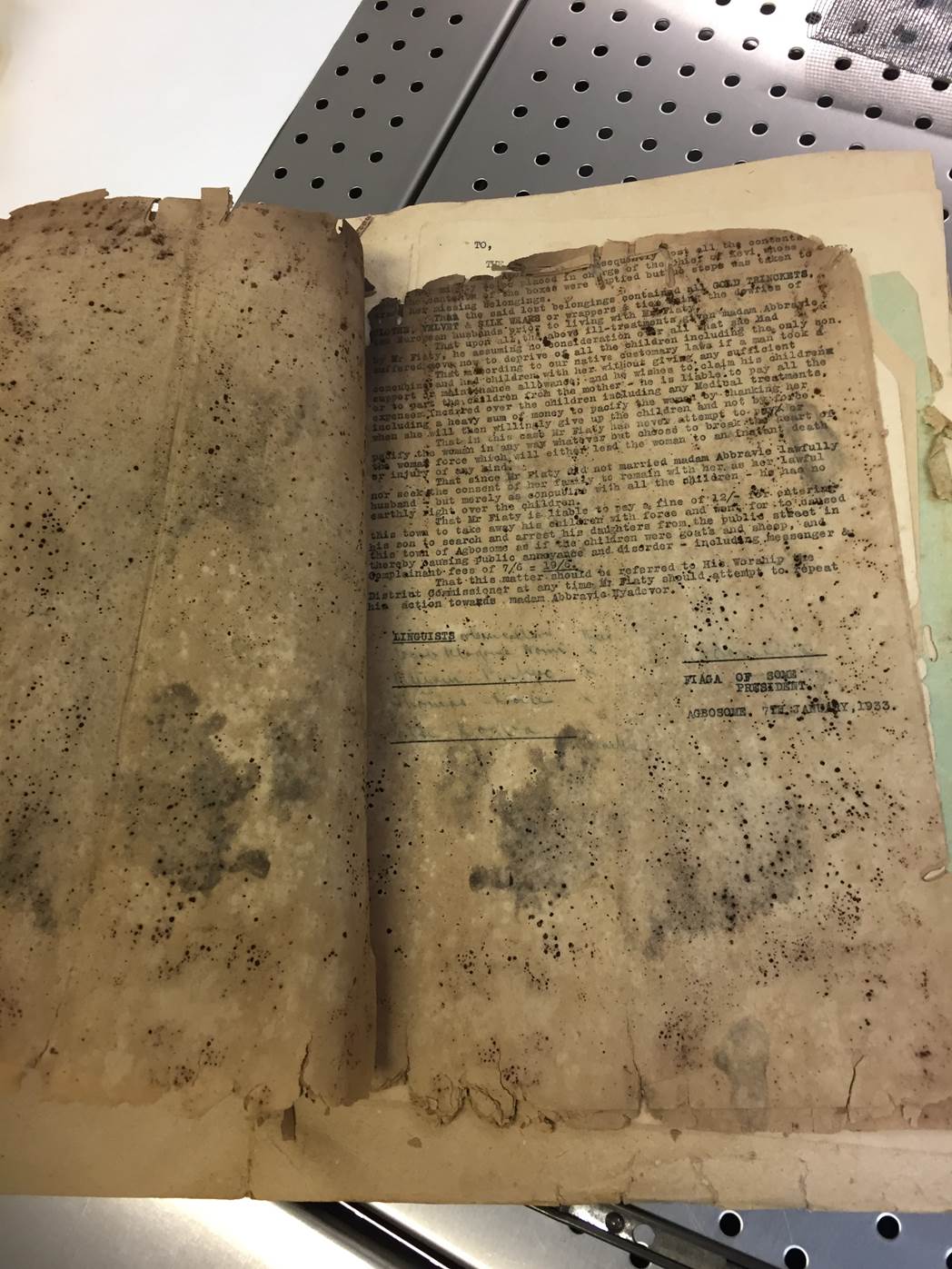

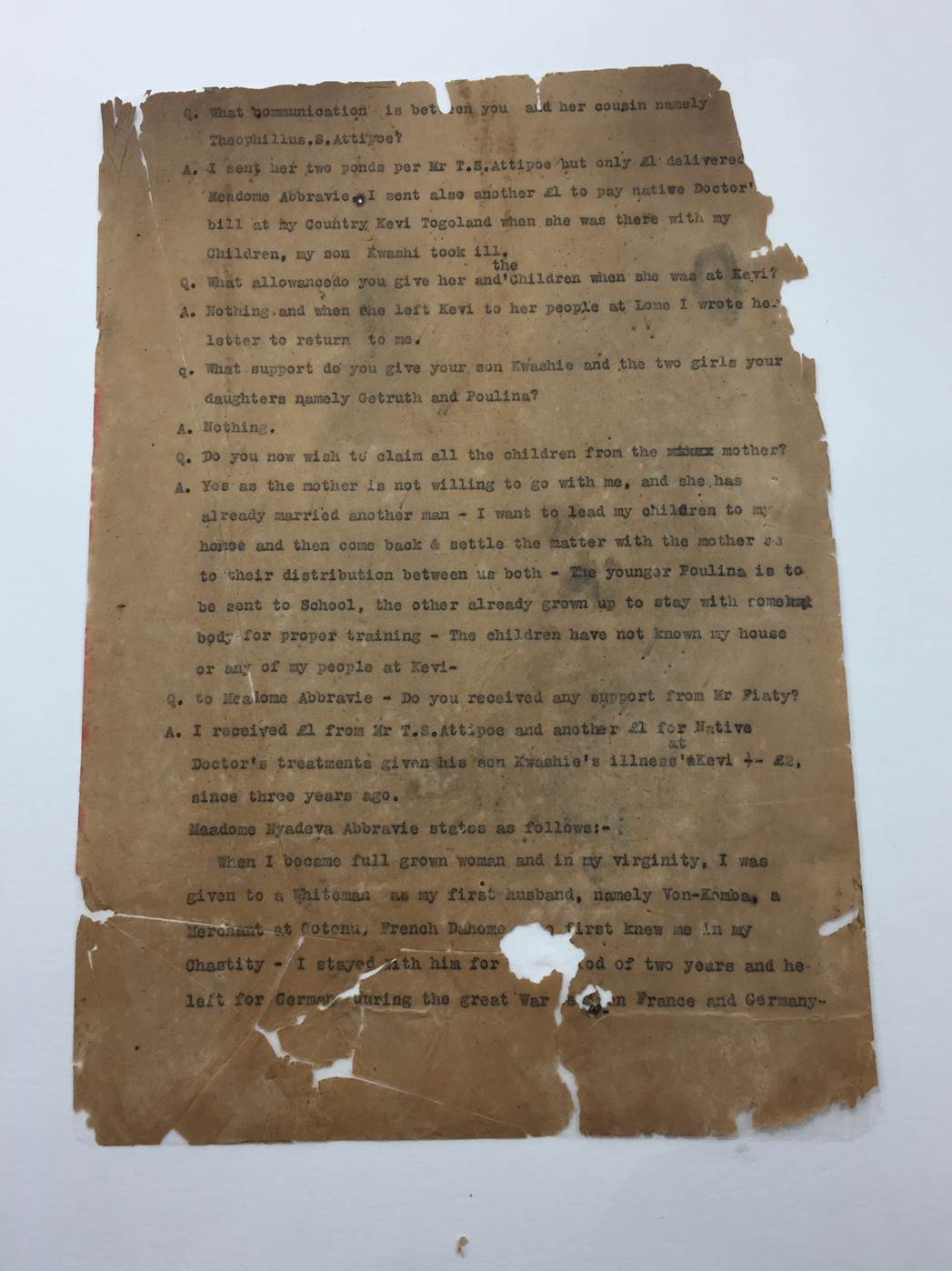

Many of the documents were a poor quality wood pulp paper, which had suffered in the humid tropical climate of Ghana. Non-archival storage, which is not unusual for family papers, had caused additional problems for the collection; the paper suffered deterioration by mould growth, degradation of the iron gall ink, rust from metal fasteners and insect damage. The result was brittle discoloured pages that were incredibly fragile and difficult to handle. Evidently much of the collection could not be handled without causing additional damage to the documents and could not therefore be catalogued or scanned, which made the conservation treatment indispensable.

A year ago part of the collection was treated by another conservator in our Digitisation Services Conservation team as the first phase of this project, which was funded by the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust. The remaining documents (which were in the worst condition) were to be treated in this second phase and the whole collection digitised at the end of it. The second phase, including the image capture, was funded by a successful Heritage Lottery Fund bid.

The collection arrived in the studio in boxes sealed with cling film to avoid mould contamination of other collections and to prevent spores causing health issues for staff.

The first necessary treatment was therefore mould cleaning. The documents were not all affected, but the treatment of all of them remained crucial to ensure that no mould spores remained in the collection. During mould cleaning, the documents are placed on a suction table and cleaned with a soft brush attached to a specialized vacuum cleaner in order to remove the mould spores.

Some cases were more difficult than others. A particular bundle of documents was infected with a type of mould that left the paper very fragile and the pages breaking into pieces.

During mould cleaning – the documents were infected with a type of mould that left the paper very weak and fragile

After mould cleaning, all the documents were brought back to the studio to be reassessed and to decide the treatments to follow. There were three categories of treatments based upon the condition of the documents:

- Flattening, which applied to the vast majority of the documents

- Tear repair with remoistenable tissue (gelatin based adhesive pre-coated on Japanese repair paper, where the adhesive is reactivated with a small amount of moisture), which applied to most of the cases where the paper itself was in good condition

- Lining, repair and consolidation of whole papers with Klucel G (Hydroxypropylcellulose, a cellulose ether) at 2% in isopropan-2-ol (isopropyl alcohol), which was applied to the very fragile documents that were either weakened by mould or by the deteriorated iron gall ink which had burned through the paper

- Poster of Japan before conservation (the pieces were flattened, reattached and the edges repaired)

- Poster of Japan after conservation

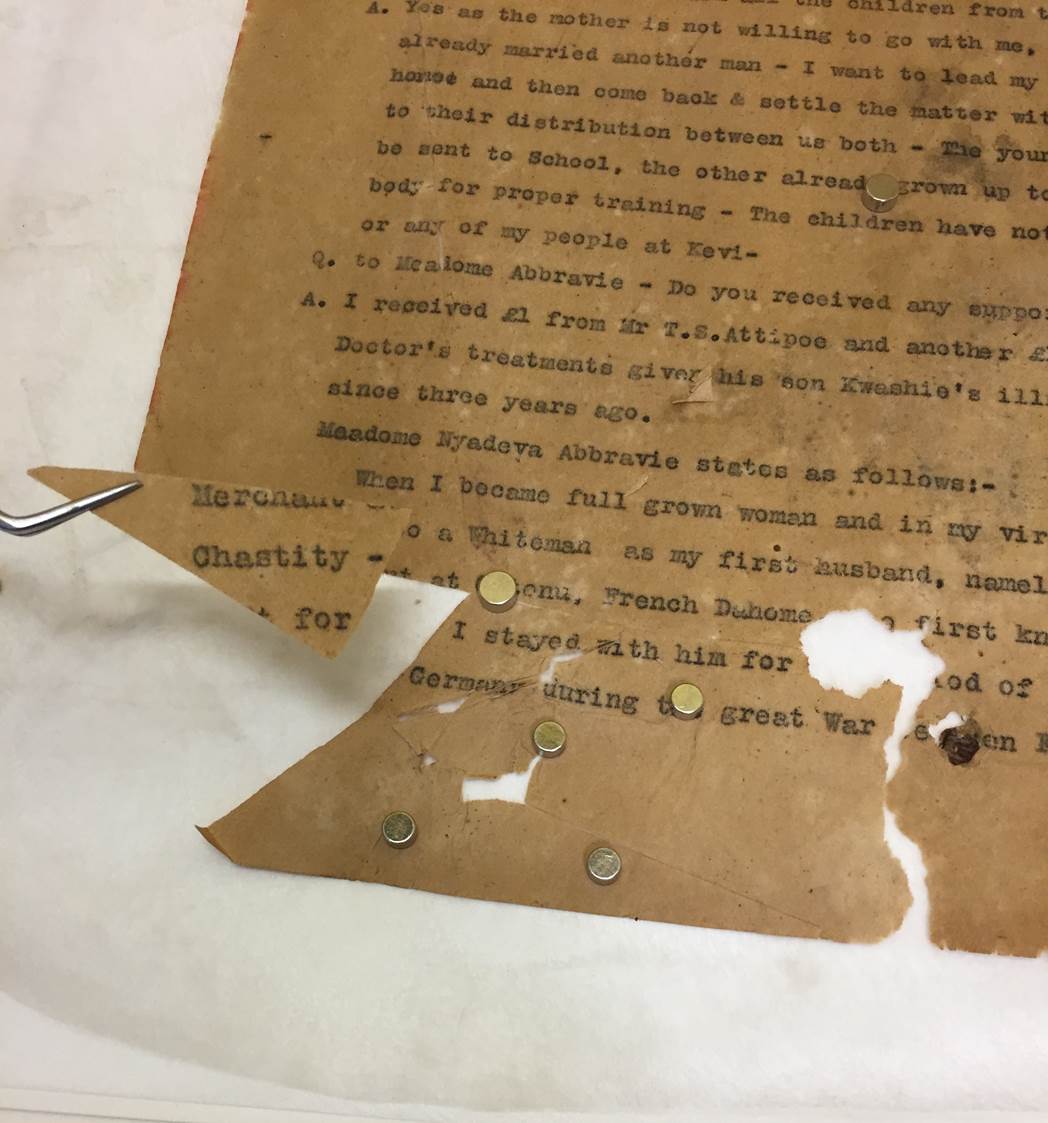

Lining the documents was one of the most challenging tasks of the project; I needed to keep them as flat as possible while applying the lining paper, and in order to realign the tears and detached pieces. I used small magnets to help keep the documents flat while the solvent evaporated, allowing the Klucel G to dry so that the document fragments were held together as one, and the lining was concluded.

- During consolidation (the use of small magnets was of great help while attempting to realign the document pieces. The magnets were supported by a thin piece of metal board covered with blotting paper and placed directly under the document)

- After consolidation

After the treatments were concluded, I made new four flap folders to enclose the documents, which were then placed in new boxes.

One of the finished boxes

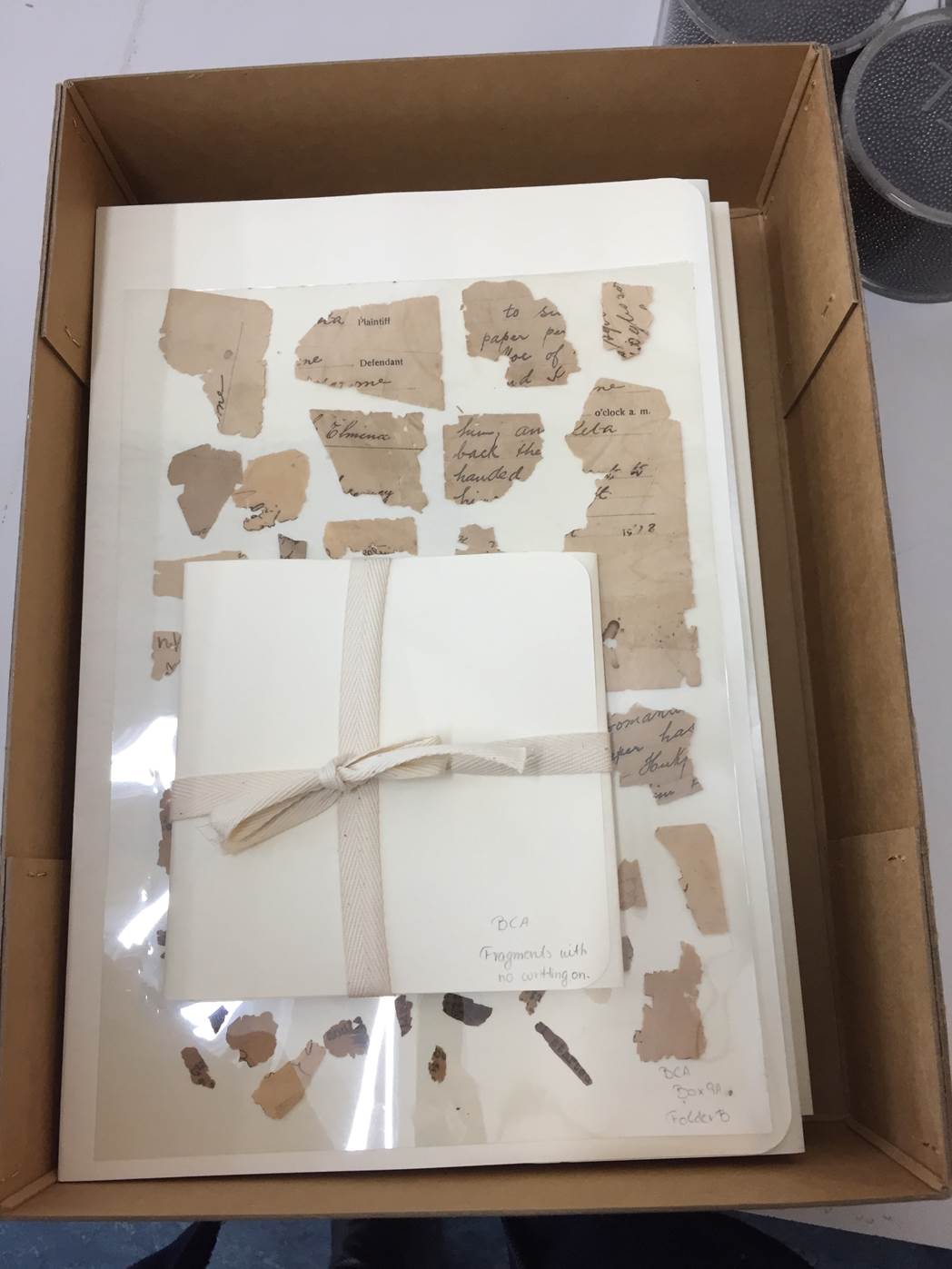

Additionally inside each box a number of fragments were found from various documents, some of which I managed to place back in their original place. The remaining fragments, which had no identifiable home were placed in a melinex sheet and secured in place with a spot welder.

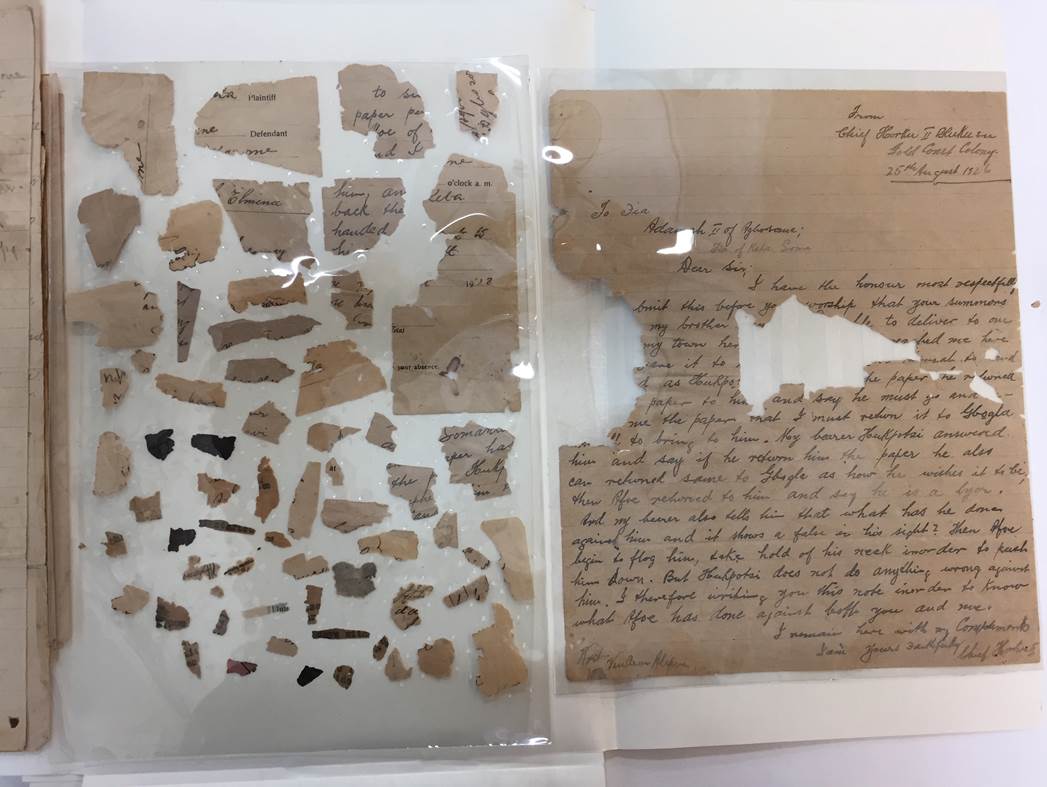

At the end of the project I had the opportunity to quickly survey the whole collection before it was sent back to the Black Cultural Archives; I was delighted to find that some of the existing fragments from phase two of the project matched documents conserved in phase one. I was able therefore to replace those too and in one case to complete a small jigsaw puzzle.

The melinex piece with the fragments and the document found at the last check

The document after the fragments were put in their original places

After conservation, the condition of the collection was transformed and was stable enough to be digitised by our Digitisation Services team.

Working on the Adamah Family Collection was challenging yet fulfilling and I hope it will be widely (and safely) enjoyed in its material and in its digital form for many decades to come.

For any further access to and information about the collection please visit the Black Cultural Archives’ website: www.bcaheritage.org.uk

Except indicated otherwise, all images are the author’s personal photographs.

[…] interesting blog post from the UK National Archives about preserving black British […]

” preserving black British ”

Really! ‘Black’ is a political term, not a colour! So a capital B, please.