Two of the key challenges facing The National Archives in the digital age are

- the need to provide new ways of accessing digital archival records

- the desire to make digital archival records available for computational analysis

As we touched upon in our recent blog post, we now need a model that describes our records as data.

We will have ever-increasing amounts of original digital content – the ‘voice of government’, if you will – that we will want to process, index, analyse and compute over. But we will also have all the contextual digital information associated with the creation, dissemination and curation of that content over time: in other words, all its metadata.

When we recently attempted to model just what this metadata might be, we decided to take as detached an approach as possible, focusing on the characteristics and provenance of the metadata, rather than the perhaps-more-usual approach of categorising the metadata by its function. This was deliberate: not only can the same piece of metadata have more than one function, but in the future there may well be new functions for our metadata that we can’t even predict today. We also see this as an intrinsically archival approach to thinking about metadata. Archivists have traditionally been very interested in the provenance of their collections (i.e. where historical records come from and who created them). Now the provenance of the metadata has an equally important focus.

In our modelling so far we have identified what we are informally calling the seven pillars of metadata. We’ve labelled these: Legacy, Primary, Secondary, Supplementary, Derived, Control, and ‘Meta’. To take each in turn:

1. Legacy metadata

For The National Archives, this refers to contextual metadata that had its origin before a record is transferred to us. This might be, for example, an audit trail of the record’s authorship as it passed through its creating department, or the record’s context when stored in its original file system or content management system. In a wider sense, legacy metadata may even relate to the contemporaneous corporate history of that originating department.

2. Primary metadata

This refers to attributes that are intrinsic to a digital object (even if they are recorded separately to it in some structured way): for example, a file’s name, extension, file type, format, size, dimensions, resolution, date/time of creation/last access/last modification, author, editor, and so on. Sometimes primary attributes may originate externally to the digital object but become intrinsic to it, such as geocoding calculated by a digital camera and stored in its images’ EXIF metadata.

3. Secondary metadata

This includes those attributes of a digital object that are manually (or automatically) created by an official organisation and then maintained separately to the object in some controlled format. This is the mainstay of good archival practice and might be any of the following instances:

- descriptive information, such as a citable reference, description or covering dates

- system information, like IDs, sort keys, machine-readable dates

- location information, such as file folder, drive, volume or filer

- access information, such as closure/release details, use restrictions, legal status, copyright and cost

- audit information, such as origin, history, transfer, modification, redaction or substitution;

- referencing information, like semantic associations, internal links and hyperlinks (URIs/URLs)

4. Supplementary metadata

For The National Archives this refers to information about a digital object that has been contributed (whether manually or automatically) by a third party who is not part of an official governmental organisation. That metadata is now stored (and may be maintained) separately to the digital object by The National Archives in some organised way for wider use. Examples of this kind of information could include an extended description, suggested corrections, a comment and/or anecdote, an added tag, or an annotation. The information might come unsolicited from passing users or it might be the result of a concerted, crowd-sourced venture.

5. Derived metadata

This describes attributes attached to a digital object that are the result of some type of programmatic analysis or algorithmic computation. This kind of information is stored in a structured format, probably periodically refreshed, and used in applications to improve functionality. A typical example would be the binary indexes that sit behind a search engine. Other examples of derived metadata might include enhanced contextual links or descriptive tags derived through topic modelling; statistics for a corpus calculated in either a local or global context; trend spotting through the monitoring of data usage; and the assignment of probability or confidence ratings.

6. Control metadata

This, as the name might suggest, is digital information that is used to regulate a digital object, for example by ensuring that it conforms to international standards by way of format, structure or content. The control therefore might be a schema or an ontology, or it might be a digital record of file system user privileges originally allocated to a digital file. Control might relate to an associated set of instructions that determine the presentation of an object under different circumstances, such as a stylesheet. Ultimately it might actually be some application code, without which the digital object itself is effectively unusable.

7. ‘Meta’ metadata

Finally, we have even identified the category of ‘meta’ metadata, or metadata that describes metadata! Metadata is not necessarily a fixed entity; it is subject to change and – in the interest of transparency, context and temporal awareness – it would be good practice to record this change. So metadata itself could be versioned, time-stamped or signed (by what means or by whom values have been asserted or modified). We think it will become increasingly necessary to account for uncertainty and probability within metadata, especially when that metadata is no longer produced by qualified human hand; ‘meta’ metadata is a means for recording such ambiguity.

And, speaking of ambiguity, we should point out that, despite our best efforts, we don’t regard these seven categories of metadata to be mutually exclusive. There are inevitably scenarios when metadata may fall more naturally into one category or another depending on circumstances. Take the example of geocoding in EXIF data: this could be said to be ‘derived’ metadata as it is machine-calculated, but its inclusion in a digital image’s internal metadata at the time of capture make it feel much more like ‘primary’ metadata, both logically and physically.

Nonetheless, we hope that the benefits of deconstructing metadata in this way will emerge when it comes to processing the imminent tsunami of digital content from the digital age. We will need ever more automated ways of contextualising this content – and the better differentiated our metadata, the easier that task will be. Description can take many forms but it will be increasingly important to be able to differentiate official human from unofficial human and approved algorithmic from unendorsed algorithmic descriptions.

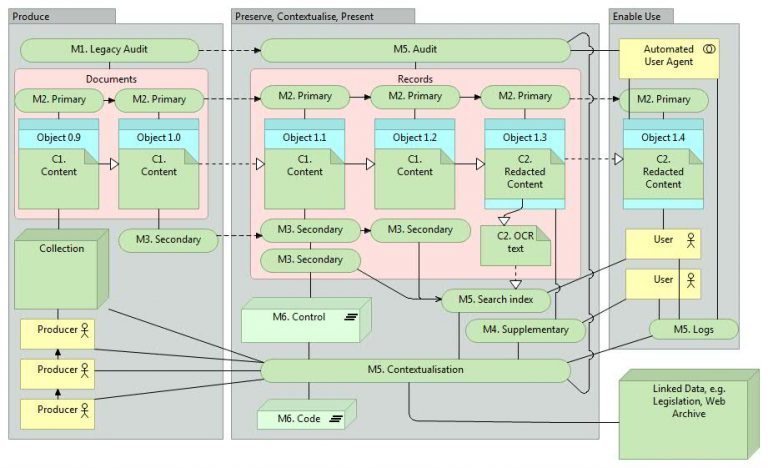

In our last blog post we referred to The National Archives’ Digital Strategy and included our visual representation of the four routes by which a digital archive can offer value to its users: Preserve, Contextualise, Present, and Enable use. This time we are accompanying our blog with a visualisation that shows a digital document’s transition from the government department that produces it, through the digital archive, and on to eventual re-use by the public. This continuum will hopefully help to visualise how the seven pillars of metadata have a part in those four routes to value:

A visualisation showing the process by which a digital document transitions from the government department that produces it, through the digital archive, and on to eventual re-use by the public

We were delighted that a number of people from different parts of the world contacted us after our last blog post. Please continue to stay in touch; we are keen to learn from and share with others facing similar challenges. If you have been thinking about your records as data or have any interest of a related nature, we would love to hear from you. Please either comment below or email discovery@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

[…] http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/digital-archiving-seven-pillars-metadata/ […]

Great post Matthew! Managing all of those layers of metadata underlines the importance of constant repair work, as presented in the D-Lib paper “Broken World vocabularies” by Lovins and Hillmann (see http://www.dlib.org/dlib/march17/lovins/03lovins.html). We’ll organise a workshop at ULB on May 31st with both hands-on tutorials on topic modeling and word embeddings and more conceptual papers. Hope we can discuss this and perhaps have you on the program when I’ll be at TNA next week. Kind regards, Seth

[…] From The National Archives Blog: […]

I remember writing a paper on Epidata, about 10 years ago, which essentially covers, what you call meta-metadata!

[…] billet sur son blogue portant sur les sept piliers des métadonnées de l’archivage numérique. http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/digital-archiving-seven-pillars-metadata/ [EchosDoc, […]

[…] For more on metadata, check out this link: […]