Related podcast:

Related podcast:

Digital Archives of the Future

What’s the difference between an archive and a data warehouse? How are digital archives different from other collections of data?

Perhaps the most significant distinction is intellectual control – one of our most important goals. The archive not only knows what information it holds, but it also has vital knowledge about those assets. The context of each record is vital in understanding its value as historical or legal evidence. Or, in the phrase coined by sociologist Alvin Ward Gouldner, ‘Context is everything’.

What does it mean to have intellectual control over a digital archive? Our Digital Strategy explains that there are four categories for the value the digital archive offers its users: preserve, contextualise, present, enable use. There’s no other kind of institution that contextualises in the same way as an archive. Supplying the context is our archival superpower, conferring value on otherwise random, unauthenticated pieces of information.

Interior of a digital tape library

Traditionally, there has been a key distinction between historical context and archival context. Understanding the historical context of a record is to know what was happening at the time of its creation: knowing where and how the events it describes or clarifies fit into a chronological sequence of events. From the archive’s point of view, this has been the job of the historian – helping you understand the big picture so you could recognise where your puzzle piece fitted into it.

An archivist might be interested in historical context but, fundamentally, we believed that wasn’t what the archive was here to deliver. Our job was to help the user of the record understand enough of the context of its creation and use to be able to make an assessment of its evidential value. Who created it and what was their role? What influence and significance did that person or institution have? Under what circumstances was the record created, and to what end? Why was it selected for permanent preservation? How does its custodial history affect its value?

That was the vital information that the archive possessed, and had to deliver to record users. We’ve always done this through the medium of an archival catalogue, the key to unlocking our records – the catalogue provided the information about the information that you needed be able to make sense of it.

Digital records are making new demands on us when it comes to establishing intellectual control over a collection.

We will rethink how we describe and contextualise digital records. We need to adopt an entirely new approach to record description based on user needs… We need to explore breaking the tight association between individual records and the description and look at more flexible approaches.

our Digital Strategy, 2017-19

We’re having to rethink how we provide context. What kinds of contextual description should we deliver to the users of our digital records? What kinds of metadata do we need to gather from the people who create digital records at the point when those records come to the archive? How much detail should we derive and create by processing those records ourselves, so we can enrich descriptions and contextualise the records?

We have published a position paper which outlines the evolution and current state of cataloguing practices for digital records at The National Archives. This lays out our approach and some of the work we have done so far, and in particular it describes the new status and significance of contextual description in a digital archive:

Born-digital and digitised records share a new existential challenge: record properties around veracity, accountability, authenticity and integrity – their ‘recordness’ in one word – are not found in the digital object itself, but in the metadata that accompanies it, which becomes inextricably bound with it. Metadata therefore becomes part of the record.[ref]Digital Cataloguing Practices at The National Archives, March 2017[/ref]

You can read more about our thinking on how to model metadata and its provenance in our recent blog post, The Seven Pillars of Metadata.

‘We will explore new opportunities for contextual description’[ref]The National Archives’ Digital Strategy, 2017-19[/ref]

We have amazing opportunities to rethink how we establish intellectual control using modern technology when we can accession records that are so much richer, with information about how they have been created and used embedded in their very fabric. Email is a good example of this: each message incorporates copious information about threading and linking, dates of interaction, the people who have received it, and so on.

We need to seize the opportunities to capture much more context (while still retaining the contextual curatorial information for the whole dataset being transferred from a creator at a given time). And we need to do more thinking about the computer models that we create to assist us in appraising and selecting records. We’re starting to develop machine learning systems to help us in the process of selection. In turn, the way these systems are designed and built will now become an important piece of context about why some digital assets have been kept and why others haven’t. How much information will users expect about the system that originally identified and selected the records made available to them?

‘We will investigate how best to manage uncertainty in our data about records’[ref]The National Archives’ Digital Strategy, 2017-19[/ref]

So far we have been able to accession what we regard as the ‘first generation’ of digital content – born-digital records, digital surrogates and digitised records (essentially digital versions of paper documents). But we’re facing the onslaught of an untamed second generation of born-digital content already accumulating within government departments – a ‘Digital Wild West’ where we can no longer depend on the traditional certainties of robust authenticity or clarity over who created a record, its timescale and consistency of format. It’s likely to be extremely difficult to discipline this lawless data within the strictures of a traditional online catalogue.

When we use contextual information that’s been generated by a computer, we can’t guarantee its absolute veracity, or relevance. It’s possible that some ‘fake news’ might infiltrate the metadata. For example, you may have a ‘last modified’ date for a document – but what level of likelihood is there that that is actually when that file was last modified in a meaningful way? This level is something we can express through ‘probabilistic description’.

Probabilistic description is about acknowledging in a transparent manner that data is imperfect and embracing uncertainty. We are considering the introduction of confidence ratings in our future metadata for born-digital and other records.’[ref]Digital Cataloguing Practices at The National Archives, March 2017[/ref]

We also need to take into consideration that people may want to study digital records in aggregate rather than individually: this will affect the kind of information that users need about them. While we will still offer a ‘view’ of individual records for our ‘readers’, we must also make records available for computational analysis, enabling ‘data users’ to work with records at scale and ask very different types of research questions.

‘Digital records can contextualise each other’[ref]The National Archives’ Digital Strategy, 2017-19[/ref]

There are some really exciting new contextual possibilities. The proliferation of digital records within government has been commensurate with the rise of the world wide web. Government is now putting so much more information about itself into the public arena. We’ve been capturing this in our UK Government web archive; we’re now approaching a very exciting point where we’ll be able to start contextualising digital records with the background details that government was sharing about itself on the web at the time. And of course there are other web archives that provide wider context about what was happening on the web – and in the world – at the time.

Suddenly we will have an opportunity to contextualise each record within a multiplicity of records of a globally deployed information system. We will need to plan how we might link up with other memory institutions and web archives to achieve this.

Reaping the benefits of intertwingularity

The traditional archival catalogue is hierarchical in structure: up until now, hierarchy and structure have been key elements in delivering archival context.

The richness of the context – of the intellectual control – available in a hyperlinked world is so much greater than we have traditionally been able to achieve. We’re entering a time when archives can tap the benefits of what philosopher and sociologist Ted Nelson called ‘intertwingularity’:

Everything is deeply intertwingled. In an important sense there are no ‘subjects’ at all; there is only all knowledge, since the cross-connections among the myriad topics of this world simply cannot be divided up neatly.[ref]Ted Nelson, ‘Computer Lib: You can and must understand computers now/Dream Machines: New freedoms through computer screens — a minority report’, 1974[/ref]

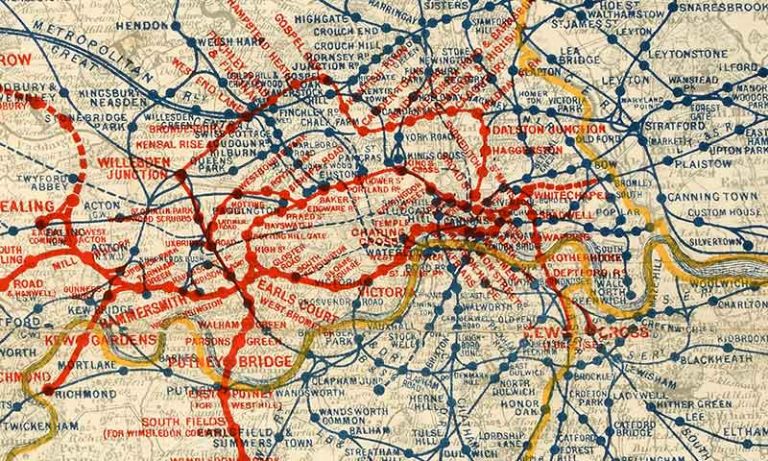

Different kinds of information can contextualise each other. The District Railway Environs map, 1898. Catalogue reference: RAIL 1034/69

The knowledge and information that users can pull together about our assets is on the cusp of becoming immeasurably much greater and more intricate.

We have a lot of work still to do here at The National Archives to make sure that we’re equipped to deal with the richness and complexity of the tide of information coming our way – and that we will be able to exert the levels of intellectual control that our users will count on. But it’s an exciting challenge, and we’ve some made excellent progress so far.

If you are working in this area, or you have an interest in any of the themes touched on in this post, we would love to hear from you. Please either comment below or email discovery@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

The problem with digital records is that (apart from being boring and just metadata) is it is difficult to established what is ‘fake’, at least with paper records that can be worked out and tested. Whilst TNA has invested a lot (far too much in my view) in digital records the papers records have been left out and the results are clear to see (poor descriptions, wrong series and files closed for more than 100 years and even for 500 years).

…

«An archivist might be interested in historical context but, fundamentally, we believed that wasn’t what the archive was here to deliver. Our job was to help the user of the record understand enough of the context of its creation and use to…» For data archiving (structured content) we need historical context to. Why was the data gathered, by whom, which methods did they employ, what definitions did they use, when and where was the data collected, what was the validity etc. And moreover, what does it mean? What rules were applied when aggregating the data, by what application. I’m not talking about a paragraph of text, but e.g. a number. Or a row of numbers. Documents do in most cases contain that some context in the contents itself, or that context is not very relevant. But when we do only add process or archival metadata to the data , we shut ourselves out for historical research on raw or aggregated data in the long run.

E.g. definitions for unemployment are changing over time. So when I want to compare unemployment figures in a historical sense, I need to now what definitions where used when the figures where compiled. And what groups where taken into consideration, e.g. women were mismeasured in labour statistics a century ago.