As I very often tell my friends and colleagues, not all archaeologists are spies. I promise. I must recognise, however, that archaeology provides an almost perfect cover for a bit of spying on the sly. Archaeologists are experts on local culture, they know the terrain well, they speak the language of the region they excavate, and they’re good at codes – trust me, if you can decipher cursive hieroglyphs and cuneiform inscriptions, you can crack any code.

Archaeology in the Middle East had always been a question of prestige mixed with geopolitical issues. In 1906, Sir Nicholas O’Connor, the British Ambassador in Constantinople, saw the opening of a German Vice-Consulate in Mosul, for the assistance of German diggers nearby, as an ‘unmistakable symptom of the increasing interest of Germany in these regions’. Similarly, in 1912, the British Resident in Bagdad, John G. Lorimer, urged the India Office to send archaeologists to Mesopotamia.

Since archaeologists are, quite frankly, historical, cultural peeping Toms, is it that surprising that archaeology and intelligence had such close links during the First World War?

Use of archaeologists as spies. Catalogue reference: FO 882/27.

The most famous, popular British archaeologist-spies undoubtedly are Thomas Edward Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia, and Gertrude Bell.

Lawrence’s archaeological romance started in 1909 in the most unromantic way ever: he was hired by David Hogarth, then Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, to draft an inventory of the museum’s potteries. In 1910, Hogarth got a concession to dig at Carchemish (Jarabulus, Syria) on behalf of the British Museum. The excavations were conducted under the direction of Charles Leonard Woolley and T. E. Lawrence. There is always much more to archaeology than a mere cover for intelligence gathering, and they did make a few stunning discoveries, but the team at Carchemish seemed more focused on the progress of the Bagdad Railway than on digging.

In 1913, Woolley and Lawrence were sent to the Sinai under the auspices of the Palestine Exploration Fund ‘to clarify the history of occupation of this area of the Southern Negev by examining and mapping the archaeological remains from all periods’. Although Lawrence and Wooley compiled a huge amount of valuable archaeological data, this survey, ‘the wilderness of Zin’, was in fact a smokescreen for a military topographical survey conducted by Captain Stewart Newcombe, who would later work with Lawrence in Arabia, and his Royal Engineers.

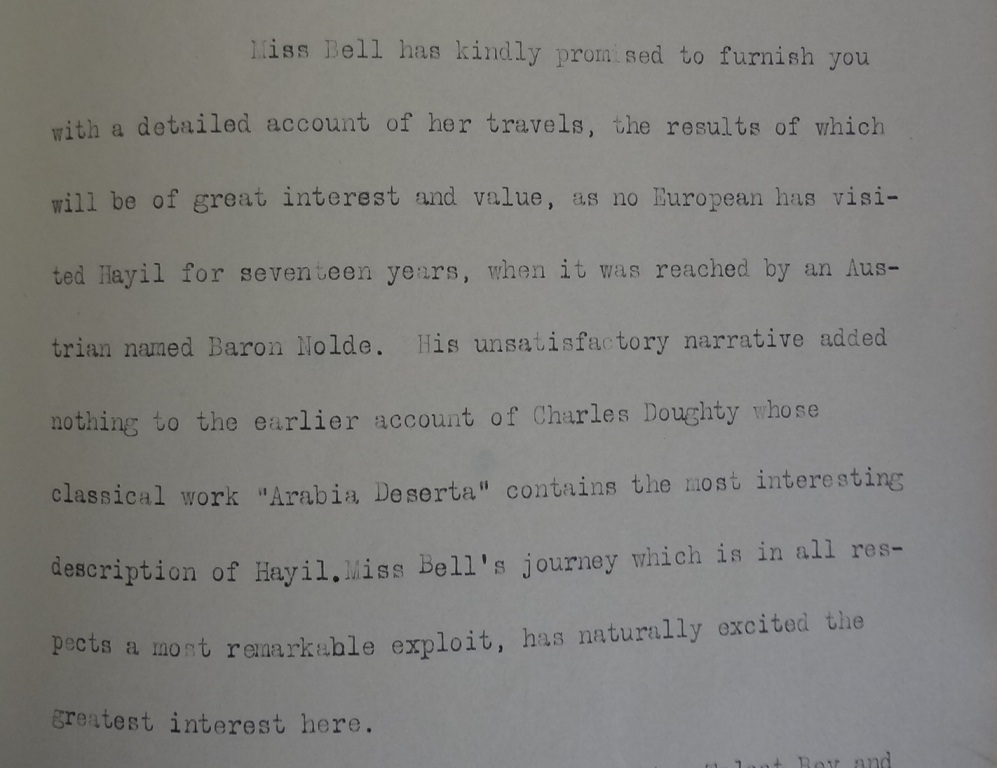

Gertrude Bell had travelled through the Arabian desert from January to May 1914, wishing to ‘trace the frontier line of the “Limes” of the later Roman Empire and to re-examine some early Mahomedan palaces’, and while the Ambassador in Constantinople, Louis Mallet, had ‘declined all responsibility for her safety’ he had also recognised how useful her reports were going to be.

When the war broke out, archaeology suddenly seemed trivial, but archaeologists were to play a leading, if somewhat shadowy, role.

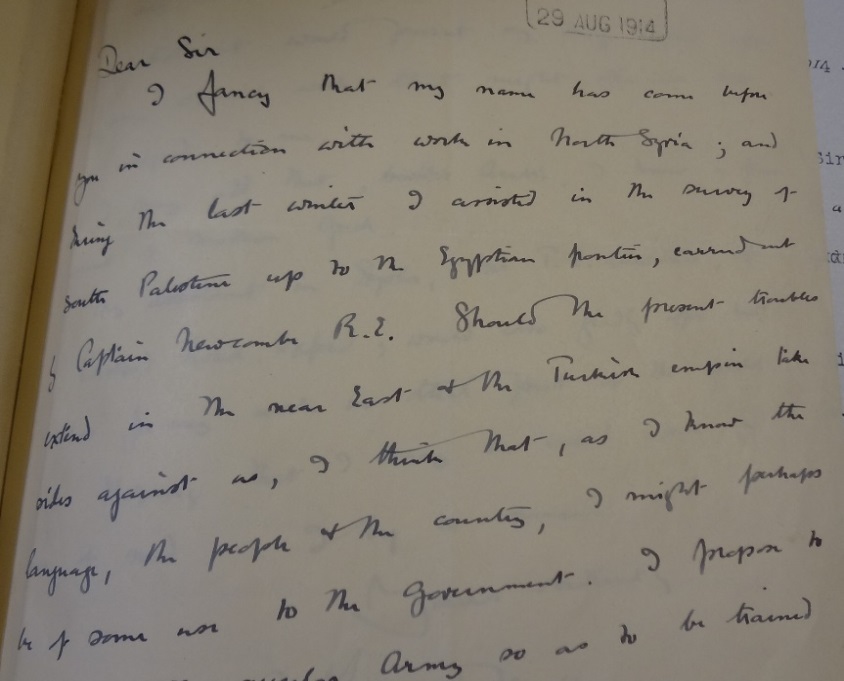

In August 1914, Leonard Woolley wrote to the Foreign Office, offering his services and those of ‘his assistant in Syria,’ T. E. Lawrence. ‘I fancy that my name has come before you in connection with North Syria,’ he wrote, ‘I think that, as I know the language, the people and the country, I might perhaps be of some use to the government.’

The note sent four days later by the Foreign Office to the Army Council shows that Woolley had not exaggerated his own importance: ‘these gentlemen are known to this Department to possess a very competent knowledge of Turkey and the Turkish language (…). Sir E. Grey thinks therefore that the Army Council may be willing to give their favourable consideration to the offer.’

Gertrude Bell was quickly sent to Arabia to collect information on tribal history, and Hogarth ended up in the Geographical section of the Naval Intelligence Department. These archaeologists turned agents then regrouped in the intelligence department of the Egyptian Army in Cairo, and in that of the Indian Expeditionary Force D in Basra.

The Germans were also using archaeologists as agents. Baron Max von Oppenheim, notably, who excavated extensively in Tell Hallaf, northern Syria, was known to the British as ‘The Kaiser’s spy’. He took the head of the Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient (Intelligence Bureau for the East) to gather intelligence and spread pan-Islamism.

Middle Eastern archaeology was (still is) a small world. All these people were connected in one way or another: Lawrence had come across Max von Oppenheim in Syria, Gertrude Bell wrote to Lawrence regularly, using a rather familiar tone, and her closest friend, Janet, was Hogarth’s sister.

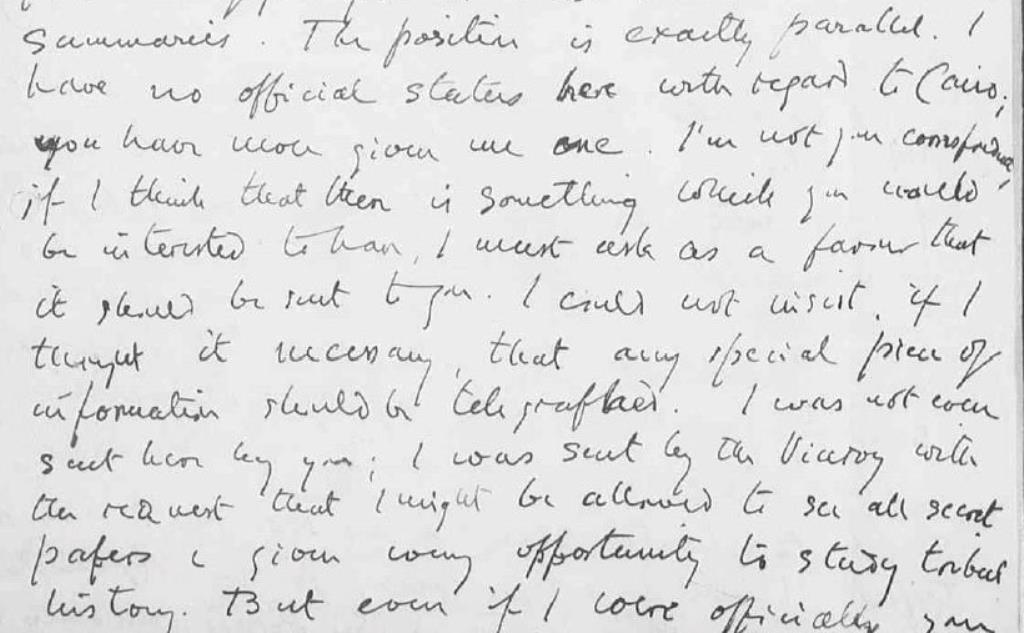

The intelligence community working in and on the Middle East was extraordinarily peculiar, not only because of its members and their archaeological connections, but also because of its rather informal organisation. As British diplomat Sir Mark Sykes pointed out, Lawrence was, at the beginning, providing ‘unofficial assistance’, while Gertrude Bell communicated information through private letters. When she found out that parts of them were copied into the Arab Bulletins, she wrote an enraged letter to Hogarth, reminding him she wasn’t his correspondent and had no official status with regard to Cairo.

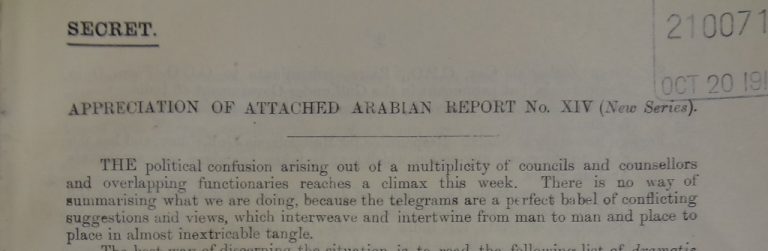

The Arab Bureau was created in 1916 in an effort to harmonise British political activity in the region. It had to deal with a very vast territory, covered by agents who reported to different entities and were not used to reporting to anyone. Sykes, who described the Bureau as a ‘Babel of conflicting suggestions and views’, expressed it very well in October 1916: ‘it may be safely said that, with the exception of the ancient constitution of Poland, it would be difficult to find a precedent for so complex or unworkable a political arrangement as the British system which has evolved itself in Arabia since the war broke out in August 14′. Archaeologists were an essential cog in the wheel of this ‘unworkable arrangement’.

The romanticised image of the archaeologist as a bold adventurer is well-embedded in popular culture but, once again, not all archaeologists are spies, not all spies can be archaeologists. Max von Oppenheim was a brilliant scholar, but a rather poor spy (although the Ottoman Sultan declared a jihad against France, Russia and Great Britain in 1914, it was never really followed. The Egyptian uprising the Turks counted on to open another front and divert the British from the Suez Canal zone never happened). Lawrence wasn’t exactly the dashing warrior in billowing robes portrayed by Peter O’Toole, but there is no denying he was a much better spy than archaeologist.

Regardless of their missions and actual results, close links were established between archaeology and covert intelligence, and the archaeologists did their bit – digging for King and Country.

[…] This article delves into the prevalence of archaeologists working as spies during WWI. Two of the coolest […]

[…] blog by Dr. Juliette Desplat highlights two famous archaeologists who were, indeed, spies. Digging for King and Country discusses how Gertrude Bell and T. E. Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia, became spies […]