Over 1 million British men were disabled by disease or injury during the First World War. Around 41,000 British servicemen returned from the war missing one or more limbs. This equated to 11,600 cases of lost arms and 29,400 cases of lost legs. Hospitals and homes were set up around the country to help these men – before, during and after the provision of artificial limbs, if required. Fitting a limb could be a lengthy procedure, and there was still more to be done in the form of rehabilitation afterwards. Rehabilitation typically took on two strands: employment, and sport and recreation. This blog post will focus on the employment of rehabilitation – and a pretty unique employment opportunity at that.

The Brighton Diamond Factory was started in 1917. The buildings for this were built and equipped with money mostly provided by Sir Bernard Oppenheimer – a South African-British diamond merchant and philanthropist. The goal was to train men in diamond cutting and polishing, and to bring Britain centre stage in this industry.

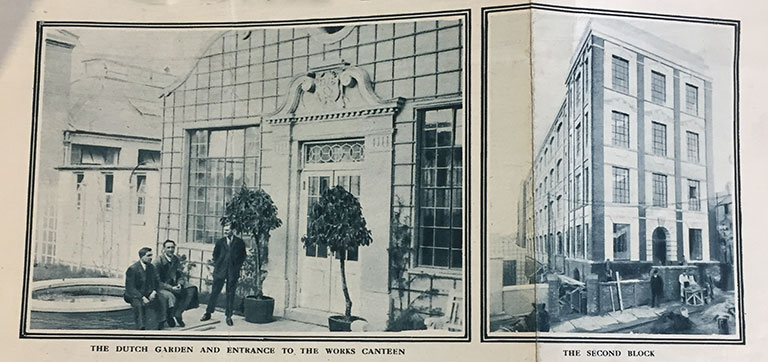

PIN 15/15: The outside of the factory

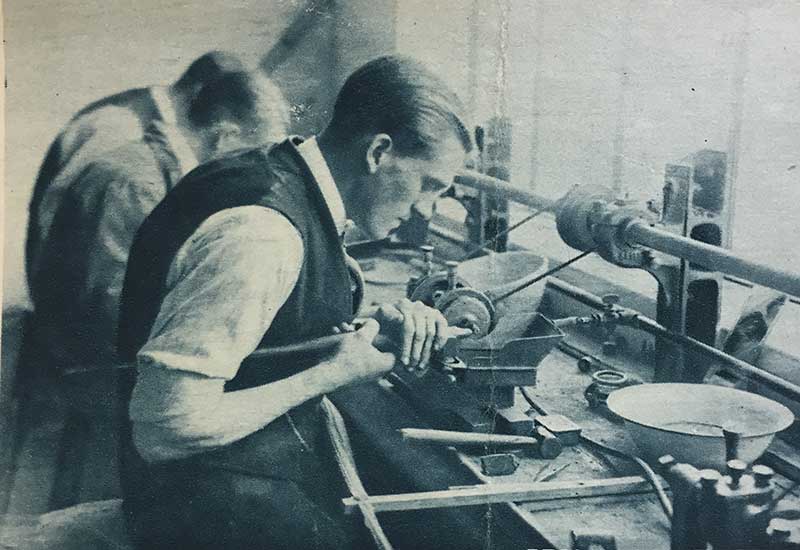

Disabled ex-servicemen were carefully selected and trained up in the factory: selection was restricted to those who had lost a leg, and careful enquiries were made as to the past character of the candidates. The arrangement was that the government would pay maintenance allowances for periods of six to nine months and the company would pay the remaining costs, including the salaries for the instructors that they imported from Belgium and Holland. Diamond work was not something that had been an industry found in Britain up until the point, so it made sense that experts had to be brought in. Subsequently, smaller branch factories were set up in Wrexham, Cambridge and Fort William. One report notes that the rooms in which the men were working were well lit and warm, which would have helped create a safe, comfortable environment for these men.

By the beginning of 1919, Oppenheimer believed that the scheme was working satisfactorily enough for him to want to extend the premises in Brighton. The main difficulty with this arose around accommodation for the trainees and employees. Up until that point, men were housed in single room accommodation. However, the majority of them were married and, having come from all over the country, they naturally wanted their wives and families to be in Brighton too. As a result, the Local Authority began making plans for a housing scheme for these men, while many prominent people in the area began to offer help in finding accommodation for the workers. Hostels were also provided to accommodate men, and eventually the difficulty was overcome and the extension of the factory was possible.

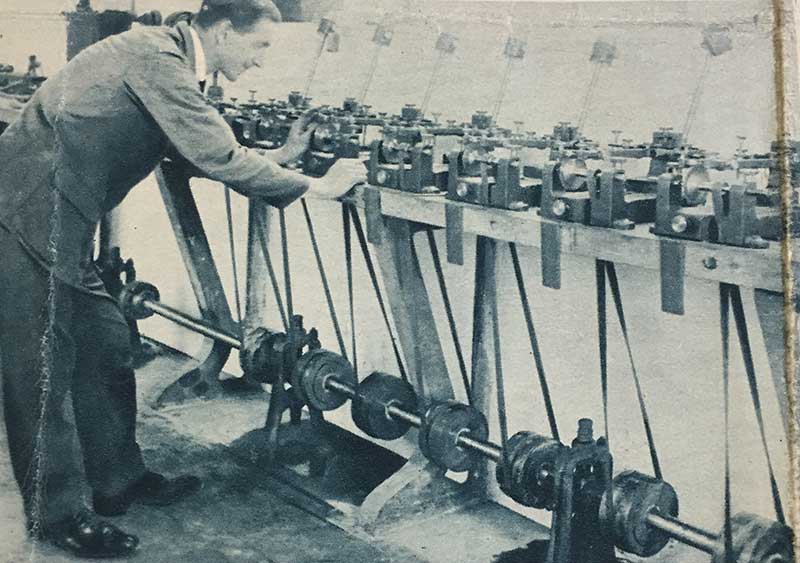

PIN 15/15: Man sawing diamonds in the factory

In 1921, there was a sharp slump in the diamond industry. Oppenheimer died early in 1922, after which the remaining directors decided to close the three branch factories and reduce the running costs in Brighton. As a result, around two thirds of all the men who had been working for the company were discharged. They were offered alternative courses of training instead. During the following year, the company struggled to carry on with business and eventually closed at the end of 1922.

PIN 15/15: Men cutting diamonds

By the start of 1919, around 500 men had been thoroughly trained in diamond cutting and polishing. Interestingly, and probably unsurprisingly, the men were not allowed near diamonds initially: instead they did all of their practising on marbles, until they were proficient enough not to make mistakes with such an expensive commodity.

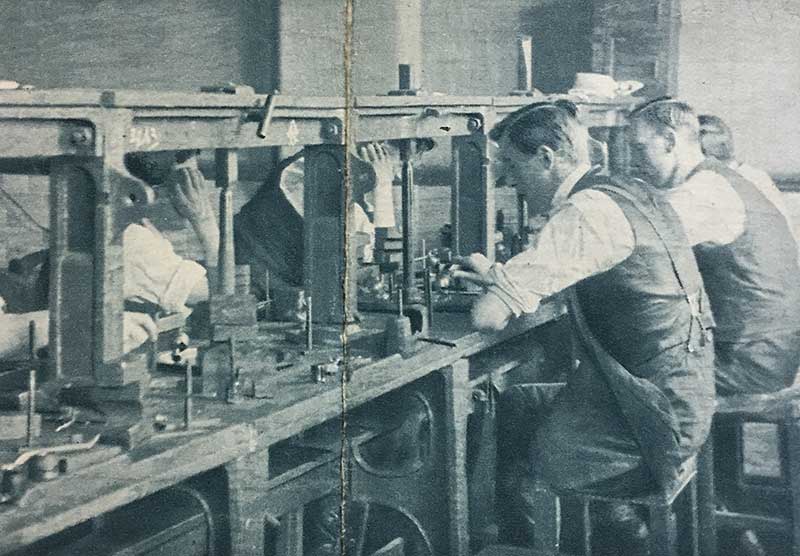

The company wanted to make it very clear that this was not charity and that they were training these men up so that they would be able to have a career in the industry. They were also being paid as they progressed through the training and then being employed by the factory. Initially, a typical weekly maintenance allowance was £2 a week, including pension. At the end of the six to nine months of training, the man would resume his pension and gain a minimum wage of £2 for a working week of 45 hours. After this, the amount the man earned depended on himself, and his weekly wages would advance with the progress that he made in the factory. Those who had been in the factory for at least a year were earning on average £2 15s a week, and after two years it is estimated that they should be able to earn from £4 to £6 a week. All of this was based around the proficiency and the productive capacity of the men.

PIN 15/15: Diamond polishing

Rehabilitation and employment for disabled ex-servicemen after the First World War is an area in which some research has been undertaken, but I think the diamond factory at Brighton is an institution that won’t be as well known. It also serves to highlight the variety of trades that were available to these men, despite the fact that they were missing limbs.

This blog marks the beginning of a series of blogs for Disability History Month. Keep an eye out for more between today and 22 December.

Was there a similar exercise after WW2

I recall my father being offered to train as a jeweller after he returned after being a Far Eastern Prisoner of War but after a while he had to give it up as he couldn’t bear to be confined in a small room

Yes, it takes a lot out of patience and attention out of you to groom yourself as a cutter or polisher. But, it’s certainly a great effort to bring so many of our servicemen under the housing scheme and utilize their dedication towards the rebuilding of the nation.

My grandfather ,Thomas Hughes (1897 -1950) originally born in Llanddeiniolen, Caerns, lost part of his kneecap when he was shot by a sniper in WW1 and for a time worked at the diamond cutting and polishing factory at Acton in Wrexham which closed in 1923. He later trained as a hairdresser and had his own business at 47, Rhosddu Rd Wrexham.

I am working in this industry for over 45 years now!

I always highly value very old polishers or bruters with conventional techniques. They are the real master cutters till to date with highly skilled practical knowledge, true passion and dedication they simply had developed their skills just getting themselves patiently trained in polishing marbles before they could touch with their hands the expensive diamonds.

Today this industry is highly developed just because of the unique traditional skills!

I have only recently discovered that my grandfather Archibald Berry, who was very badly wounded in WW1, losing a leg and ending up in hospital in the Royal Pavilion in Brighton for some time, trained as a diamond polisher before retraining in clerical and admin work, presumably because of the downturn in fortunes described above. He was from a family of master hairdressers but was unable to continue in that profession because of losing his leg.