This blog is published as part of International Archives Week, which explores the theme of ‘Designing the Archives in the 21st century’.

Fifty years ago, the specifications for a new building to house the bulk of the nation’s records was produced. Covering everything you might expect, they detailed the plans for a safe, secure, controlled environment for the collection, with efficient document retrieval, pleasant reading rooms, conservation and reprographic studios – and, finally, the capacity for 25 years of growth. The building was planned with the future in mind, meeting the needs of the 21st century even in the 1970s.

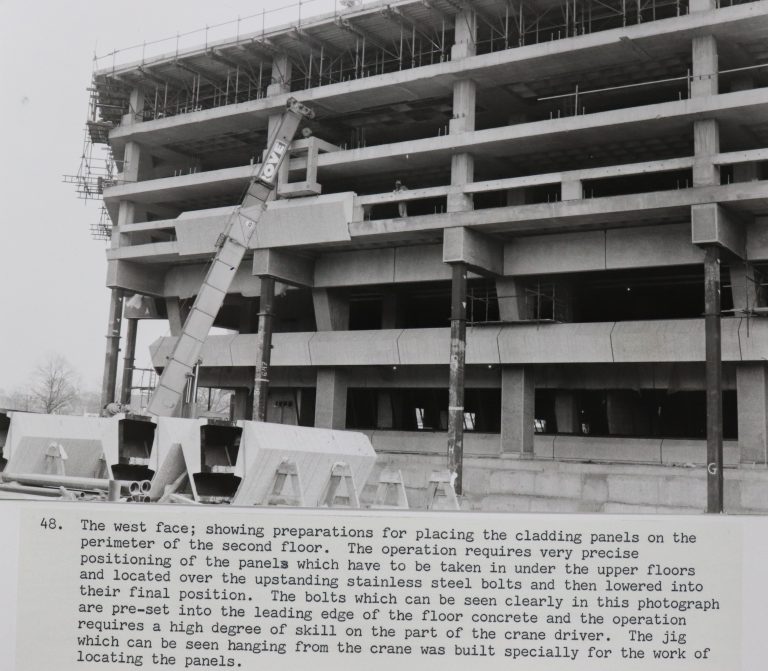

The installation of concrete cladding blocks on the exterior of Q1. PRO 62/4

The resulting building has since been referred to as a ‘Brutalist masterpiece’. The architectural team probed every last detail of the specifications, while financial constraints in the 1970s meant there was no scope for adornment or embellishment in decorative features. The building’s design was very much a case of ‘form follows function’.

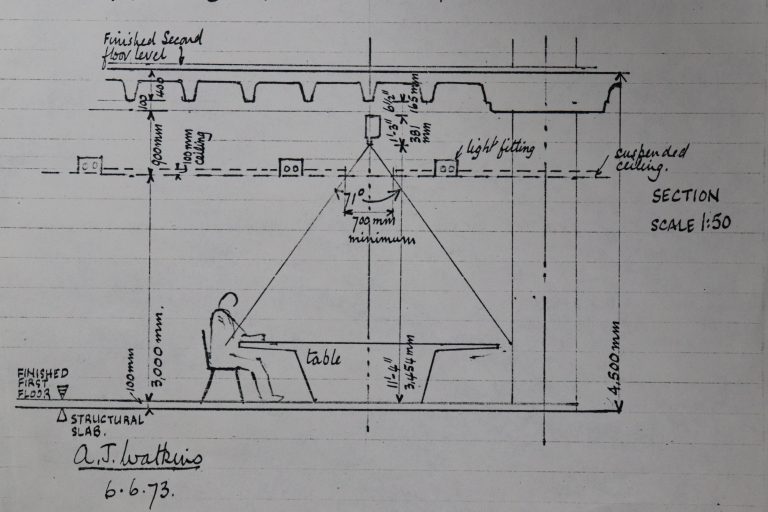

Things that we now see as commonplace in building design were revolutionary, and in some cases, archive firsts. For instance, the use of computers for researchers to request documents (at the time the existing building at Chancery Lane used pneumatic tubes). One of the earliest uses of CCTV in a public building was here in Kew, where it was used as the primary tool of invigilation in the reading rooms. Sealed-unit double glazing and full air-conditioning also featured in the pursuit of perfection for an archival environment.

Sectional diagram of CCTV invigilation. PRO 68/14

Instead of horizontal conveyor systems, experiments showed that electric trikes were much more efficient and flexible at moving documents from the shelves to the central paternoster. This system is still used to this day, although some of the trikes are pedal-powered!

Concern about the psychological impact on staff working alone in large repositories led to the incorporation of slit windows to permit natural light and piped music. Staff were co-located to a central point on each floor, rather than the original concept of allocating a staff member per zone. The slit windows made a considerable impact on the external vista of the building, creating a strong horizontal dynamic and breaking up what would otherwise have been a large featureless concrete block.

Slit windows allowed for natural light for workers inside the repositories.

Today the building is still used as originally conceived and intended, albeit with modifications to the public areas and reading rooms, and the addition in the 1990s of a second building to permit the closure of Chancery Lane.

We have a masterplan to continue the development of the building to suit the needs of future researchers and visitors. Find out more and see a preview of our future plans when our design partners go in conversation on 27 June, as part of London Festival of Architecture. For more information and bookings, click here.

The computers (all three of them) were only for ordering documents and you had to consult paper lists to find out the descriptions which were very general (e.g. ADM 188: Royal Marines: Chatham: 1868) before you could order the documents and wade through hundreds of pages. There were the ‘bleepers’ to tell you when the document had arrived. Kew was fortunate in that they had not only CCTV but in colour (an issue on which the Treasury asked as to why) and staff were also employed on plinths to monitor researchers. The one mistake for the building were the stiff doors which able-bodied people had difficulty opening and were impossible for anyone who was disabled, unfortunately door handles were still in use for the Kew extension in the 1990s. Perhaps the architects should have been asked about the Concorde flights over the building around 5pm each day and the vibration the plane caused.

An interesting post showing how things have changed. And a reminder for all that things could be worse when the inevitable day-to-day problems associated with running and maintaining a huge archive occur.

What a pity you could not reveal the names of the architects and builders. Why, indeed, is this information not shown? It would seem worthy of inclusion, since many of those seeking information about the building would like to know.

Oh, right, you can’t or won’t answer this. Sorry. My apologies for asking.