In the first few years of the Second World War, Britons’ knowledge of and interest in the situation in Japan was low. The Ministry of Information, which was responsible for producing propaganda to inform and influence people in Britain and its empire, generally concentrated on attacking and undermining Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany and, to a lesser extent, Mussolini and Imperial Italy.

At the end of 1941, the British government and its Ministry of Information had to adapt to a radically new situation. On 7 December, Japan launched its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor which caused the United States to enter the war in the Pacific and in Europe. Germany and Italy subsequently declared war on the USA and Japan launched attacks against the allies in British Hong Kong, British Malaya and the Philippines. Suddenly Britain had a new powerful ally and a new dangerous adversary, and the Ministry of Information had the task of introducing them to the British people.

In a Home Intelligence Report from 17 December 1941, it was stated that the public feeling was ‘divided between satisfaction that the United States is now actively in the war on our side, and dismay at the strength of Japan’ [ref]’Ministry of Information Home Intelligence Weekly Report No. 63’, 17 December 1941’, MOI Digital [accessed 29/07/2020][/ref].

Despite Japan’s alliance with Great Britain in the First World War, the British people did not know very much about the Japanese people before 1941. Even during the years following, knowledge and interest was limited. A Home Intelligence Special Report on public attitudes to the Far Eastern War and Japan, dated 11 July 1944, found that ‘at the most about 50% of people know even a few simple facts about the Far Eastern war’ [ref]’Ministry of Information Home Intelligence Special Report: Public attitudes to the Far Eastern War and Japan’, 11 July 1944, MOI Digital [accessed 29/07/2020][/ref]. This was no doubt due to Japan’s distance from Britain and the comparisons to the direct experience of German bombing, however it has led to the Pacific campaign being neglected in cultural memory even today.

The Ministry of Information did attempt to address this problem during the war by producing creative and aggressive propaganda about the Japanese enemy.

Introducing the enemy

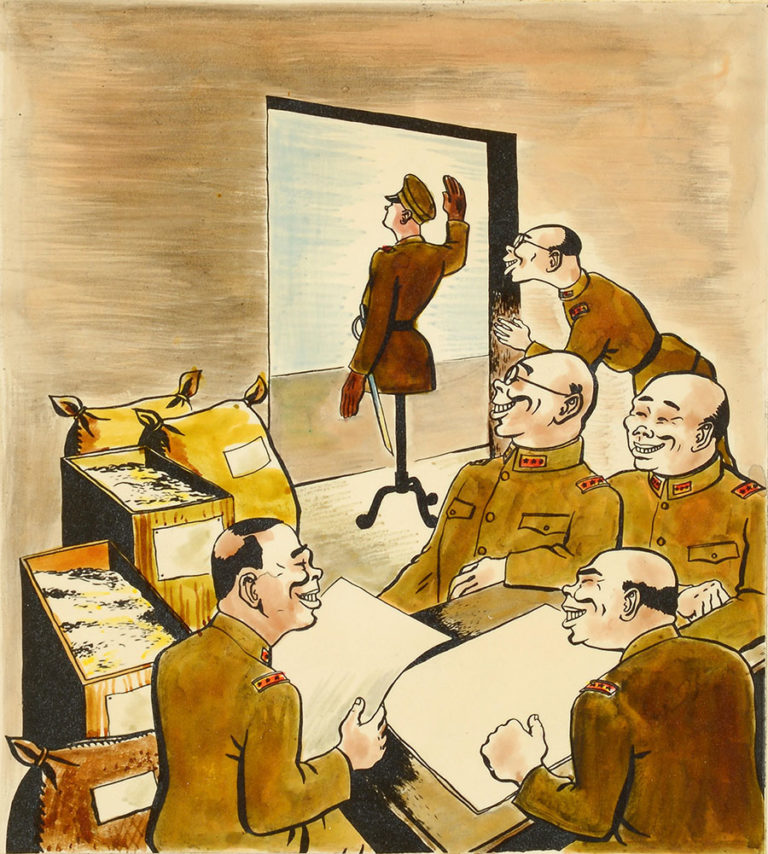

The British government felt the need to inform the people about Imperial Japan and emphasise the reasons they were fighting them. Propaganda drew parallels with Nazi Germany, focusing on negative ideas which were already well-known from other propaganda. In a pamphlet titled ‘The Japanese People’, published in 1943, Japan is described as a nation of ‘tribalism, aggression, brutality, false-swearing, density about other mentalities, contempt for women, contempt of freedom, contempt of the human spirit and negation of God’[ref]David Welch, Persuading the People: British Propaganda in World War II, (London, 2016), p. 114[/ref]. Many of these characterisations can be seen in visual propaganda, such as in this cartoon where Japanese generals are presented as dishonest and manipulative.

Another pamphlet titled ‘Japanese Aggression’ states that ‘The Japanese are a dangerous race. Japan considers itself superior to every other race’. This pamphlet relies heavily on photographs of Japanese military operations and Chinese refugees to illustrate its points.

These characterisations of people fed the existing attitudes of the British to Japan and are reflected in the 1944 Special Report from Home Intelligence. When asked what the main difference was between Britain and Japan, 23% said low wages and low standard of living, 11% no personal freedom or individuality, 11% feudalism, fanaticism and extremism, 8% godlessness and 4% family life and the subjugation of women[ref]’Ministry of Information Home Intelligence Special Report: Public attitudes to the Far Eastern War and Japan’, 11 July 1944, MOI Digital[/ref].

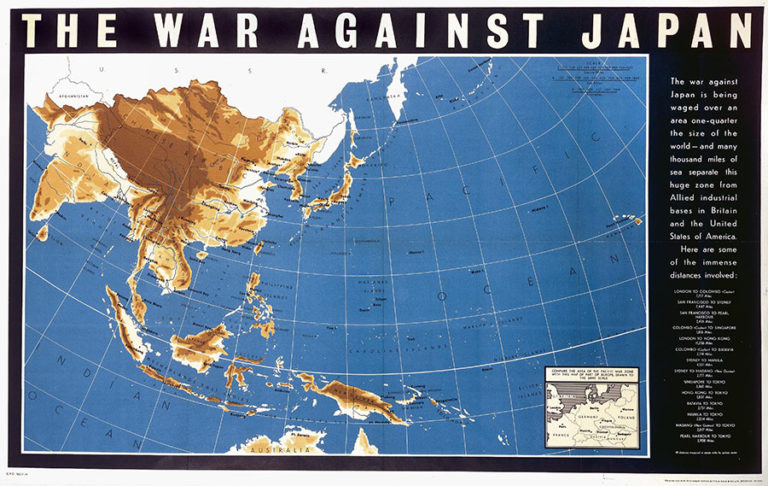

Some propaganda materials intended to educate people about the locations and scale of the Pacific war. Posters were produced which presented maps of the Pacific theatre under the title ‘The War Against Japan’. One poster held by The National Archives presents the following description beside a detailed map and a list of distances in miles between key locations.

‘The war against Japan is being waged over an area one-quarter the size of the world – and many thousand miles of sea separate this huge zone from Allied industrial bases in Britain and the United States of America. Here are some of the immense distances involved’

Racial stereotyping and dehumanisation

Racist depictions of the Japanese were common in British propaganda and these drew upon existing racial stereotypes and attitudes held by the British people. Some of these kinds of depictions are present in cartoons intended to be humorous. Japanese figures are presented as physically small, with squinting eyes, glasses and buckteeth. Some of these characteristics are influenced by American propaganda which of course had a much larger preoccupation with depicting the Japanese as the enemy.

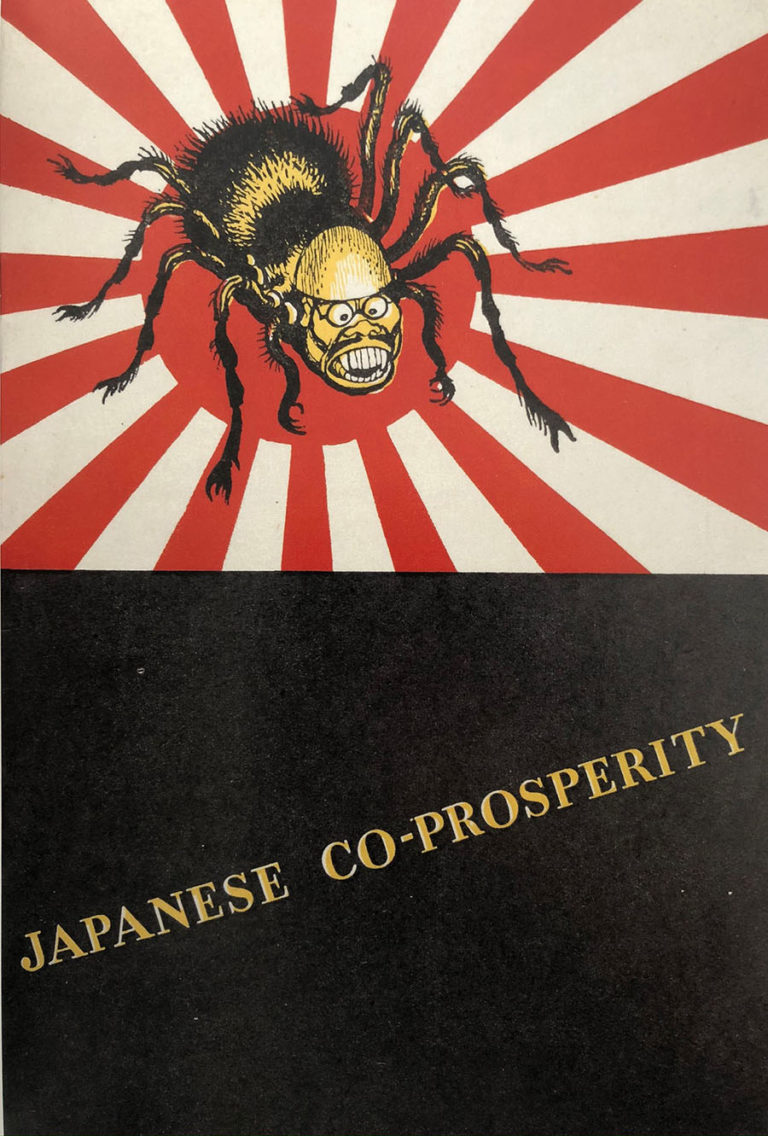

These racist depictions also dehumanised the Japanese, by presenting them with animalistic physical qualities or simply as animals. In the pamphlet below, a Japanese soldier is depicted as a dangerous spider, with the Japanese flag used to represent the spreading influence of the state over other countries. The poster mocks the concept of co-prosperity, which had been promoted in Japanese propaganda as a plan to create a benevolent Japanese empire in East Asia[ref] David Welch, Persuading the People: British Propaganda in World War II, (London, 2016), pp. 115-8[/ref].

Propaganda overseas

While people in Britain may not have been that concerned about the Pacific theatre, people living in British overseas territories certainly were. By 1943 the Japanese had occupied Hong Kong, Malaya (now Malaysia), Singapore and Burma (now Myanmar) – all British territories at the time. In spring 1944 Japan also attempted an invasion of India. One vital aim of the Ministry of Information’s work was to convince colonial citizens that the allies were committed to their defence.

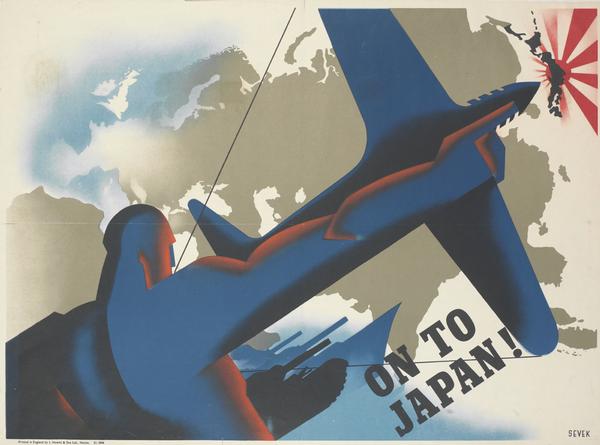

One poster designed by Austrian artist Sevek proclaims ‘On to Japan!’ The poster shows a fighter plan shaped like a bow being pointed by a soldier towards Japan, with the Japanese flag as a target. It was designed to assure people that, following victory in Europe, the allies’ next step was to defeat Japan[ref]’On to Japan!’, VADS, [accessed 29/07/2020][/ref].

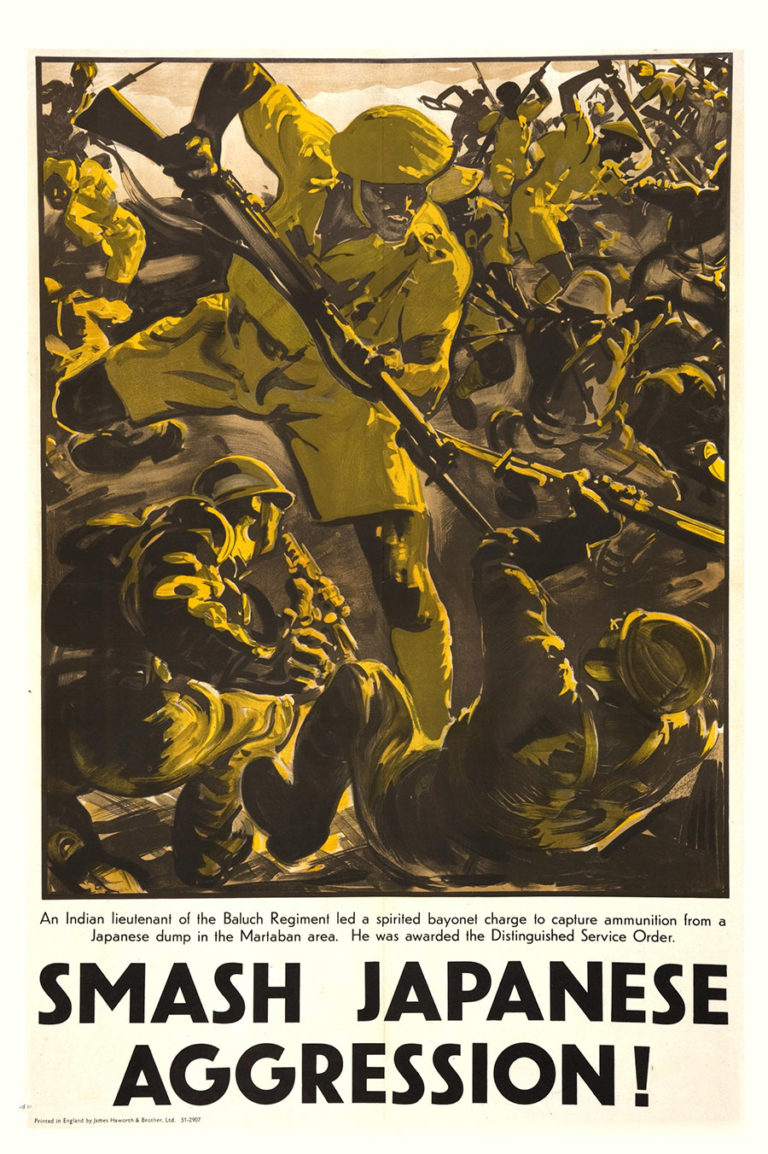

Another series of posters titled ‘Smash Japanese Aggression’ included illustrations promoting the military contributions of colonial troops. In this example below, the caption reads ‘An Indian lieutenant of the Baluch Regiment led a spirited bayonet charge to capture ammunition from a Japanese dump in the Martaban area. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order’.

Depicting Japan’s future

After Japan was defeated in 1945, there were some efforts to present a picture of a potential future of Japan and its place in the world. The 1944 special report indicated that only 42% of people thought that Britain would ever be friendly again with Japan (this was 65% with Germany). This suggests that the view of the future of Japan was fairly negative, even in comparison with that of Germany[ref]’Ministry of Information Home Intelligence Special Report: Public attitudes to the Far Eastern War and Japan’, 11 July 1944, MOI Digital[/ref].

The Ministry of Information therefore wanted to improve British attitudes to the future of Japan. Basil Charles Wright directed a film called ‘This was Japan’ for the Crown Film Unit in 1945 which presented a review of Japanese history with graphic descriptions of atrocities, but ended on a more positive note predicting the end of militarism in Japan’s future[ref]’This Was Japan (1945)’, British Film Institute, [accessed 29/07/2020]; Alan James Harding, ‘Evaluating the importance of the Crown Film Unit, 1940–1952’ (2017), p. 261, [accessed 29/07/2020]; Production files are held by The National Archives in INF 6/988 [/ref].

Propaganda concerning the Pacific campaign and the Japanese enemy was not a huge priority for the Ministry of Information, particular with regard to domestic British Propaganda. The Ministry was much more concerned with producing propaganda for overseas territories where people felt more at risk from the Japanese. The shortage of domestic visual propaganda has no doubt contributed to the Pacific campaign being neglected in memory and commemoration of the Second World War today.

As a Japanese historian, the information you provide with this blog is almost all “j’ai deja vu.” What I am interested in and want to know is the information how and to what extent the British army (or the Australian army) contributed to reorganize the state system and social structure of my country during the occupation period, especially West Japan.

An interesting post about the psychology of war – or rather the psychology of the ‘invincibility’ of the Allied fighting man, many of which although with colonial backgrounds saw themselves as superior to the Japanese.

A similar attitude can be detected in the German military of the First and Second World Wars towards troops from France’s African colonies – or indeed British forces towards more recent adversaries such as Argentineans.

Often a form of reverse psychology was used such as in the case of an Argentinean pilot who having been shot down, injured and taken aboard a British hospital ship is said to have awoken to find Gurkha troops at his bedside brandishing their kookries as apparently the Argentine forces had been told that if captured by the Gurkhas they would be eaten.

As always it would be interesting to see the mirror image – how British and other allies were depicted and stereotyped.