One of the morning sessions at 'Keeping Tracks'

Keeping Tracks was a lively one-day seminar at The British Library which addressed approaches to archiving music in the digital age. It went beyond ‘formal’ archives to the accidental archives of record labels and the Labour of Love archives of die-hard music fans. The big themes were keeping the sound recordings retrievable and playable, and the completeness of collections and their descriptions.

‘You don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone’

Unless you did a decent preservation job, that is.

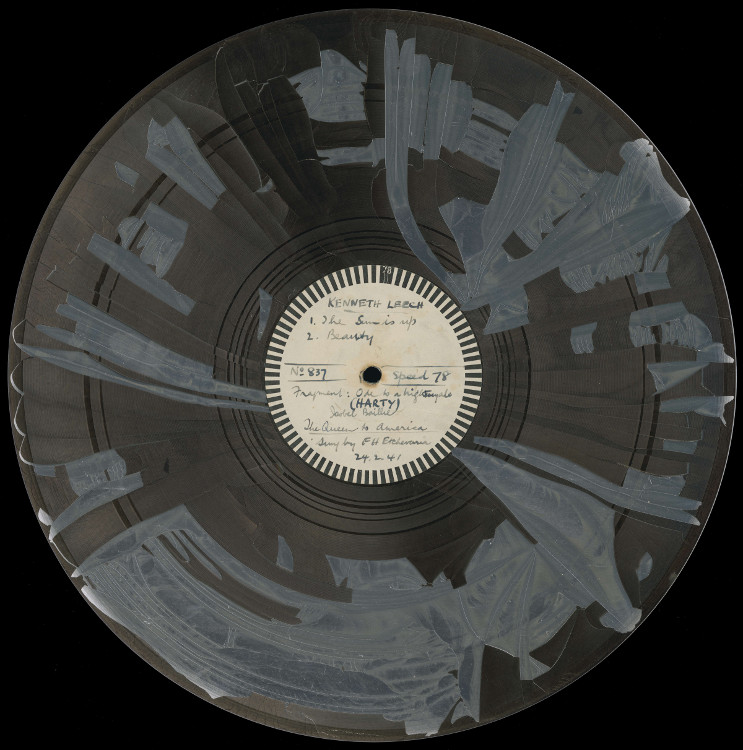

Even before the shift from analogue to digital, sound carriers and players were becoming obsolete. The BL’s Adam Tovell flashed up an alarming image of a degraded 1940’s lacquer disc to illustrate the fragility of a format and loss of content.

Delaminated lacquer disc (image courtesy of The British Library, from the KH Leech collection (C738))

Digital media are vulnerable too. It may not be a surprise that a 70 year old analogue disc format is vulnerable; it’s more shocking that 30 year old digital formats (CDR) are in danger (via obsolescence as well as degradation).

The BL has been digitising for 30 years, originally using betamax cassettes and now carried out in 10 transfer studios. Adam outlined their seven stages of sound archiving:

- Select which sound recording if you have more than one – consider formats

- Describe the physical carrier – the metadata must meet the needs of the library etc. and the end user

- Migrate to a lossless, hi-res file

- Describe the transfer process and provenance

- Check – the file and its metadata must be of ‘good enough’ preservation quality

- Ingest into a trusted repository – the BL has four locations, the main repository and three back ups

- Store the digital product for future use and go back to the start because the outputs face the same threats

He estimated it might take them 48 years to digitise everything.

Digital sound copies might yet be lost to users if the metadata is poor. The BL’s Alex Wilson introduced the joint project with Metable, called metable@BL, which aims to prevent this. In essence suppliers submit files and metadata which the BL can use to create files for delivery. This project also allows for supplementary metadata from third party APIs from Decibel and similar outfits. However the arrangement is one-way,so currently there is no facility to add BL-enhanced metadata back into the external resources – most notably a problem with the open repository, Musicbrainz.

The Decibel team talked about their graph database with data ordered by association and flexible data types. This allows for associative querying of the type: I’m looking for the recording by the man married to the woman who wrote a different work. Anyone who ever worked in a record shop will recognise that formula!

‘You can’t always get what you want’

But with a collection strategy you can possibly get what you need.

In addition to official releases, a complete sound archive could hold broadcasts – radio and TV sessions, concert performances – and enthusiasts’ material (‘bootlegs’ in ye olden days). There is no legal deposit of audio/visual material in UK. The Legal Deposit Libraries Act 2003 only applies to print media and the BL continues to be a grateful recipient of the material donated by record labels. The BL wants to nurture mutually beneficial relationships with the music industry, labels and digital sound providers such as BandCamp – they have so much expertise to share and they need material to archive. Get in touch with Andy Linehan at the British Library if you have sound recordings they can archive.

Lars Ganstad and Trond Valberg described how the National Library of Norway has benefited from a legal requirement to deposit sound recordings and they demonstrated mediaIDEditor, created to accommodate digital accessions. Their digital storage is growing at 6 or more terabytes per day, helped in part by rights owners being able to upload content directly to the archive

There was a session focused on organising and consolidating the Beggars Group archive which revealed just how much record labels need to learn from other archives; it made me think about how some of our guidance could have been useful to them. Over the past four decades their archiving approach was not much more sophisticated than storing everything in a room and relying on colleagues’ record collections to fill the gaps. Priority was based on past popularity/potential sales rather than vulnerability of ‘the record’. The Beggars Group are a good example of how business is finally understanding the value of archives, not least commercial.

Panel discussion with speakers from Ace Records, Trunk Records and The Death Waltz Recording Co.

The day ended with an entertaining panel discussion covering back catalogue re-issues and ‘lost’ soundtracks. We heard about the chaotic nature of trying to license obscure recordings and the painstaking work behind the artefacts issued by a boutique soundtrack label. And there was utter commonsense for audiophiles: an engineer, when asked by someone to recommend a hi-fi up to £50,000, replied ‘buy a £5,000 hi-fi and spend £45,000 on the room’, stressing the importance of the environment. The quotation in the title is an Ace sound engineer’s response to questions about analogue v digital sound quality in 1950s recordings…