Two years ago, while still in lockdown, we ran an online creative project with Innovations in Dementia called Connecting through Collections, which brought together two generations of women. Young women studying A levels or in further education met and interacted with older women who had led fulfilling working lives but were now living with dementia.

Our older participants loved working creatively with young people talking freely of their perspectives and experiences. They also enjoyed having the chance to share the times they had learned most about life, or themselves. Our younger participants reported how useful they had found learning about the older women’s choice of career and the work experiences that had fulfilled or challenged them. They were also able to ask questions and widen their understanding about dementia and the many challenges the illness presents.

This is Dementia Action Week and as dementia is a hidden disability, like mental ill health, autism or deafness, we were keen to explore the records of women who are often overlooked in history but who fought for their rights. We know of some such women from correspondence that features in our War Office and Pension Records. They are the disabled nurses of the First World War.

The records of these nurses, often stationed overseas near to the fighting, show how little power they held once the war was over. They corresponded with the government at a time when few of them had the right to vote, or they were wholly dependent upon families. They learned to use every strategy available to receive allowances and recognition, often confronted by inspections and attitudes that today we would find unacceptable and offensive.

Agnes

We interviewed Agnes, a former military nurse who was stationed in Hong Kong during the 1960s. While we were reviewing cases of nurses who were diagnosed with neurasthenia and other conditions after the war, Agnes was prompted to relate her own experience of the trauma of her own war service.

During the interview, Agnes offers an insight into the vocational call of the job, the sense of family she developed with co-workers and of the way military nursing has shaped who she is today. Agnes’ experience helps us view the nurses with a deeper understanding.

You can view a short snippet of the interview on YouTube (external link) or read a transcript of the snippet at the bottom of this page.

Watch a short snippet of our interview with Agnes on YouTube

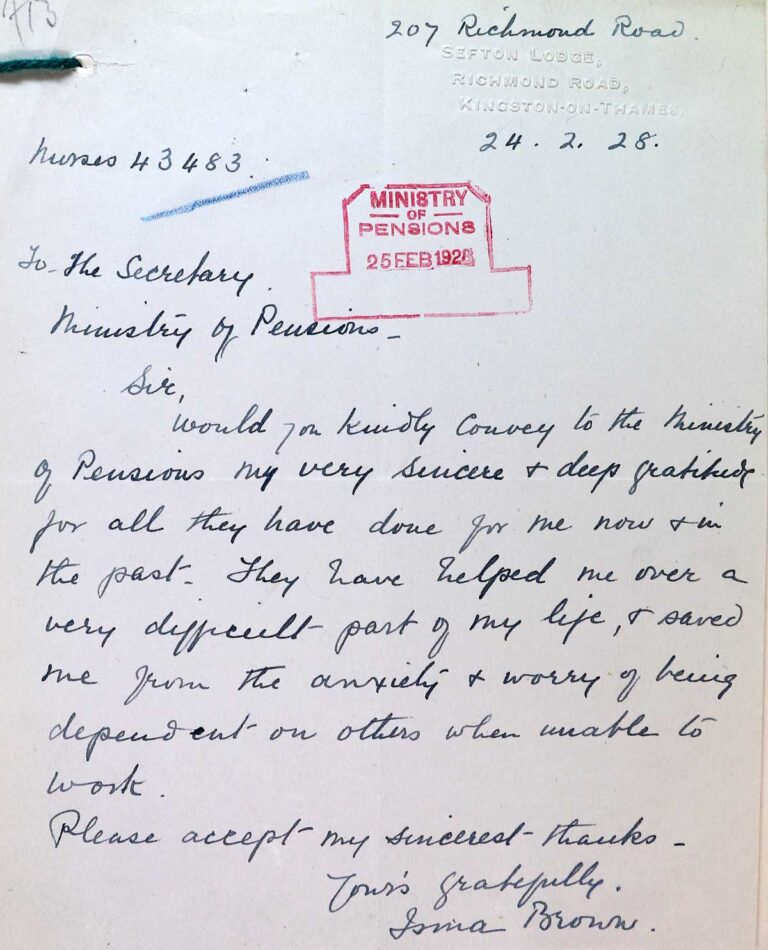

Isma Brown

Of the nurses we are researching, a few stand out. One, Isma Brown, served in the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) in Mesopotamia, France, Italy and India. She suffered greatly due to the heat and conditions in the Middle East and had a nervous breakdown in 1920 whilst working at Tooting Neurological hospital.

Isma’s age (42) and the menopause are often referred to in medical reports as a reason for the ‘exhaustion psychosis’ that affected her. Isma had to fight for recognition that her ill health was attributable to the war but in 1921 she was awarded a 70% disability pension, which was reduced to 20% by 1928.

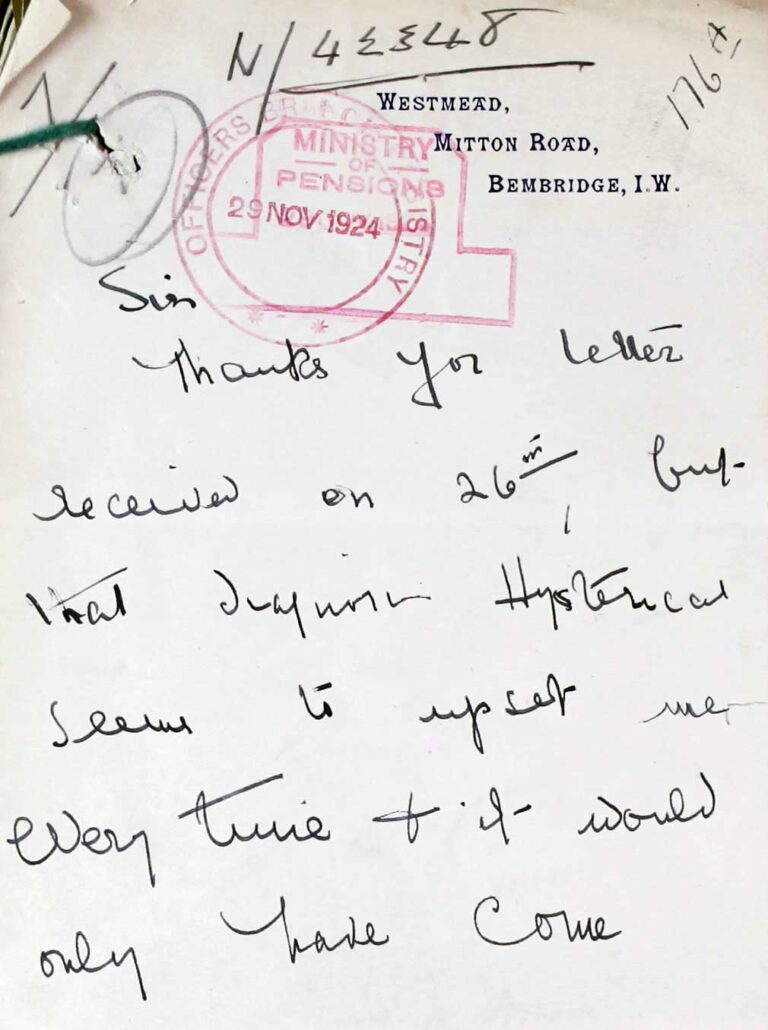

Lillian Atkins

Lillian Atkins worked as a Nursing Sister in the QAIMNS, serving in France during the First World War. She was diagnosed with Hysterical Neurasthenia (aggravated by her nursing experiences during the war), and special instructions in her medical report advise that the term Psychoneurosis should be used when corresponding with Lillian ‘as she strongly objects to the word hysterical’.

Lillian fights to have her condition recognised against an underlying backdrop of official judgement that describes her as ‘an emotional type’. Lillian’s initial award of 30% disability pension in 1920 was eventually increased to 100% in 1927.

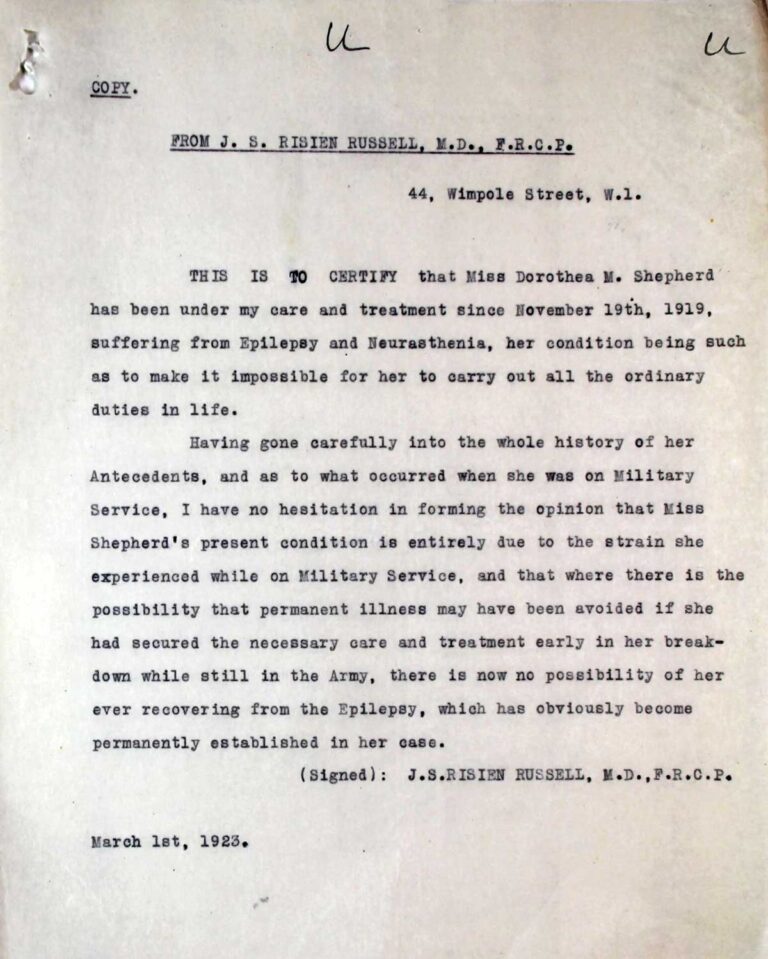

Dorothea Shepherd

Dorothea Shepherd was a ward sister in both QAIMNS and TFNS who served in France and Malta and was discharged due to ill health, including neurasthenia. She developed epilepsy after her war service which debilitated her further and led to her death in 1926, aged 41.

Our records show her family’s fight for recognition that her condition was not hereditary but entirely due to the stress of war service, aided by letters from Dr James Risien Russell, one of Britain’s first Black medical consultants. Dorothea did secure the 100% disability allowance but died shortly afterwards in 1926, of an epileptic fit, aged just 41.

Our next step is to work with artists, including Frances – a retired grants officer now living with dementia – to develop a resource that enables other people to access our nurses’ records and interact with them creatively as well as through oral testimony. We’ll let you know how we get on.

You can find out more about military nurses in the First World War in blogs like this one and this one. You can also explore the work of Innovations in Dementia on their website.

Transcript of Agnes’ interview film

Sara: We have cases of nurses from the First World War who were disabled, either as a result of the war and their nursing service. They are campaigning for better pensions or for living allowances or for the payment of medical bills.

We were particularly interested in having a military nurse’s personal experiences – your personal experiences – to help us understand and learn a different way of looking at these nurses and their lives.

Agnes: Because it was military nursing, there was a sense of adventure and I believe it formed a lot of my character and who I am today.

Sara: And one of the questions that I had, Louise, is how many organisations were involved in recruiting nurses to serve overseas or to look after soldiers here.

Louise: A lot of these nursing services were set up before the First World War. But they all seem to do something slightly different in recruiting slightly different women too.

Agnes: And in some of the cases the ladies are fighting about the words they’re using. Why are words important? Well, it’s damned important if you’re going to get thrown in a locked mental health ward.

I can’t express it, it’s only on looking back on it, It was one of the most traumatic experiences of my life.

You’ve got to learn to fight with the tools that they fight with. Oh, of course we expect that – ‘emotional’ – what time of the month is it? I was fed up hearing that.

The only way they can protest is throw the barley water. I have seen it in dementia and I stand back and say yes! Because at least they’ve got a voice.

Sara: What’s interesting is there’s this he’s treating her, but for her epilepsy and he writes a letter that says if the war office had looked after this lady before, her situation would not have been so bad as it is today.

This woman has not brought this upon herself, acknowledge that she is where she is as a result of the war. Accept it. 100% disability allowance was given.

Agnes: Who is Agnes? I remember when I got dementia someone asked me that question and I didn’t know who Agnes was. Are you going to find out who is this Agnes with dementia?

We, our generation have learned from the voices that were suppressed in our history and it’s learning to do your breathing exercises: keep calm, be gracious, as these ladies did in the letters. Be gracious, be kind to others, but be strong enough to get your needs met.

Dementia Action Week 2023 is an important event focused on raising awareness and taking action against dementia. It aims to promote understanding and support for individuals living with dementia and their families, as well as to encourage society to take steps to improve the lives of those affected by this condition. During Dementia Action Week, various activities, initiatives, and campaigns are organized to engage the public, healthcare professionals, and policymakers in discussions and actions related to dementia.